He may have been an antisemite, but he knew great Jewish art when he saw it

The exquisite work of Modigliani found an unlikely champion in Dr. Albert C. Barnes

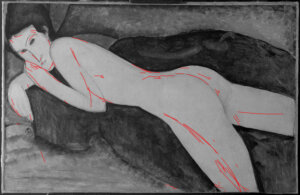

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Even in a crowded gallery room, it’s easy to spot the work of Amedeo Modigliani — the mysteriously elongated lines; the hauntingly stylized faces that characterize so many of his paintings and sculptures. But whether seen from near or far, an exquisite new exhibition, “Modigliani Up Close,” shows that the vision of this Italian Jewish artist encompasses a greater sense of color, technical complexity and emotional depth than a passing glance can reveal.

New research, conducted by a team of more than 50 art historians and conservators from around the world, informs the exhibit, affording viewers a detailed understanding of how Modigliani (1884-1920) prepared each canvas and chiseled each sculpture. You’ll learn, for instance, about the artist’s preference, particularly in his early years, for re-using old canvases, and how he would sometimes employ the shadowy remains of those under-images to enhance his own finished work. You’ll also discover the stories behind some of the myths of Modigliani’s bohemian ways.

The exhibit’s venue — the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia — also invites a closer examination of the paradoxical mind of Dr. Albert C. Barnes, the eccentric art collector who used his pharmaceutical fortune to assemble the large, impressive collection (mostly late 19th and 20th-century paintings, drawings and sculpture) that constitutes the museum he founded.

As open-minded as Barnes was in his appreciation of modern art, some of his other attitudes could be less welcoming. As Barnes Foundation associate curator Cindy Kang writes in the beautifully appointed exhibit catalogue: “Barnes was known to make antisemitic comments about dealers and art-market speculators, while passionately collecting the work of Jewish artists such as Modigliani and (Chaim) Soutine.”

To its credit, the Barnes Foundation doesn’t shy away from acknowledging the founder’s unsavory attitudes. “They are not excusable, and we grappled” with the issue, exhibit curator Nancy Ireson told me. An additional contradiction, she said, is that Barnes was eager to support overlooked artists like Modigliani. And fortunately, she said, the artistic “legacy of what he bought still stands.”

Unfortunately, Barnes’ slurs still leave a residue. Still, Modigliani’s work is itself redemptive, and it takes center stage here in all its glory.

The first work visitors see is a vibrant self-portrait from 1919, painted in the same varied shades of green, blue, ochre, brown, and black shown on the palette he holds. He sits before his canvas, his oval face serenely gazing outward, as if inviting us to enter the exhibit and view the work that fills the galleries ahead.

The palette in his hand also invites us to consider some of the new research from the international team of conservators. Back in the 1980s, art historians had tools capable of identifying only eight of the pigments that Modigliani used in his paintings, Barnes conservator Barbara Buckley told me. But the latest high-tech methods have now shown that he used “upwards of 24,” she said. “We see the tonality of the palette does change over the years, but even in his earlier paintings where he is using a fairly dark palette, a black is never just a black; he also introduces blues and reds.”

That insight helps explain the elusive beauty of the 1916 canvas “Seated Servant,” in which hidden splotches of red, as well as unexpected brushstrokes in different shades of blue, highlight the black and white stripes of the subject’s apron. It’s likely that in this canvas, like others Modigliani used, an image already existed beneath what we see.

Beneath the surface of his 1915 painting, “The Pretty Housewife,” for instance, radiographic technology discovered two other, earlier paintings that contrast with the staid stance we see of the happy young woman holding a wicker basket. But a close examination of the wicker basket itself, as well as the subject’s eyes, nose and forehead, show that he blended colors from the pre-existing paintings to blend in with or peek through the final layers of paint.

One gallery is mostly devoted to Modigliani’s alluring nudes, sitting, standing, reclining and lying down. Another consists of paintings and sculptural figures that seem engaged in dialogue with one another; mask-like faces of chiseled stone sculptures reflect the subjects of paintings. In “Nude with a Hat,” from 1908, a woman who is nude from the waist up except for the shadowy black hat atop her head is proportioned similarly to the artist’s sculptured figures. Her hat seems to be almost the equivalent of the carved headdresses of the statuary. In both genres, Modigliani’s affection for Egyptian art and African masks are apparent.

“There is an underlying spirituality in much of his sculptural work,” said the exhibit’s consulting curator Simonetta Fraquelli. Modigliani reputedly wanted to give his studio the impression of an ancient temple when he invited visitors to view his sculptures, and lit candles atop sculptured heads to create this atmosphere. The fact that the exhibit’s team of conservators discovered wax atop the sculptures seems to confirm this story, according to Buckley, the Barnes conservator.

The leftover wax may also relate to another anecdote about the artist’s work habits, as recounted by Renee Modot, wife of one of Modigliani’s closest friends, who posed for “Young Woman in a Yellow Dress” in 1918.

“I didn’t mind sitting for the portraits or some nudes,” she recalled, “but you should have seen my living room when was finished for the day. There was paint on the rug, on the furniture, all over us. He might have been likable but he was an extremely messy painter.”

By this time, Modigliani and his partner Jeanne Hébuterne were living mostly in the south of France, and the canvases from his last two years seem filled with the region’s abundant sunlight. His portraits of Hébuterne, pregnant with their child, are particularly luminous, her eyes an intense turquoise blue, the backgrounds calm, incandescent with light tones of gray, green, blue and peach.

There is no hint that the day following Modigliani’s death from tubercular meningitis at the age of 35, Jeanne, then eight months pregnant with their second child, would commit suicide. The end was tragic; our consolation resides in the work left behind, on display here in this brilliant exhibition.

“Modigliani Up Close” runs at the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, through Jan. 29, 2023.