Was Josef K. only guilty of the crime of being Jewish?

Sixty years after its premiere, Orson Welles’ adaptation of Franz Kafka’s ‘The Trial’ remains cinema’s most vivid fever dream

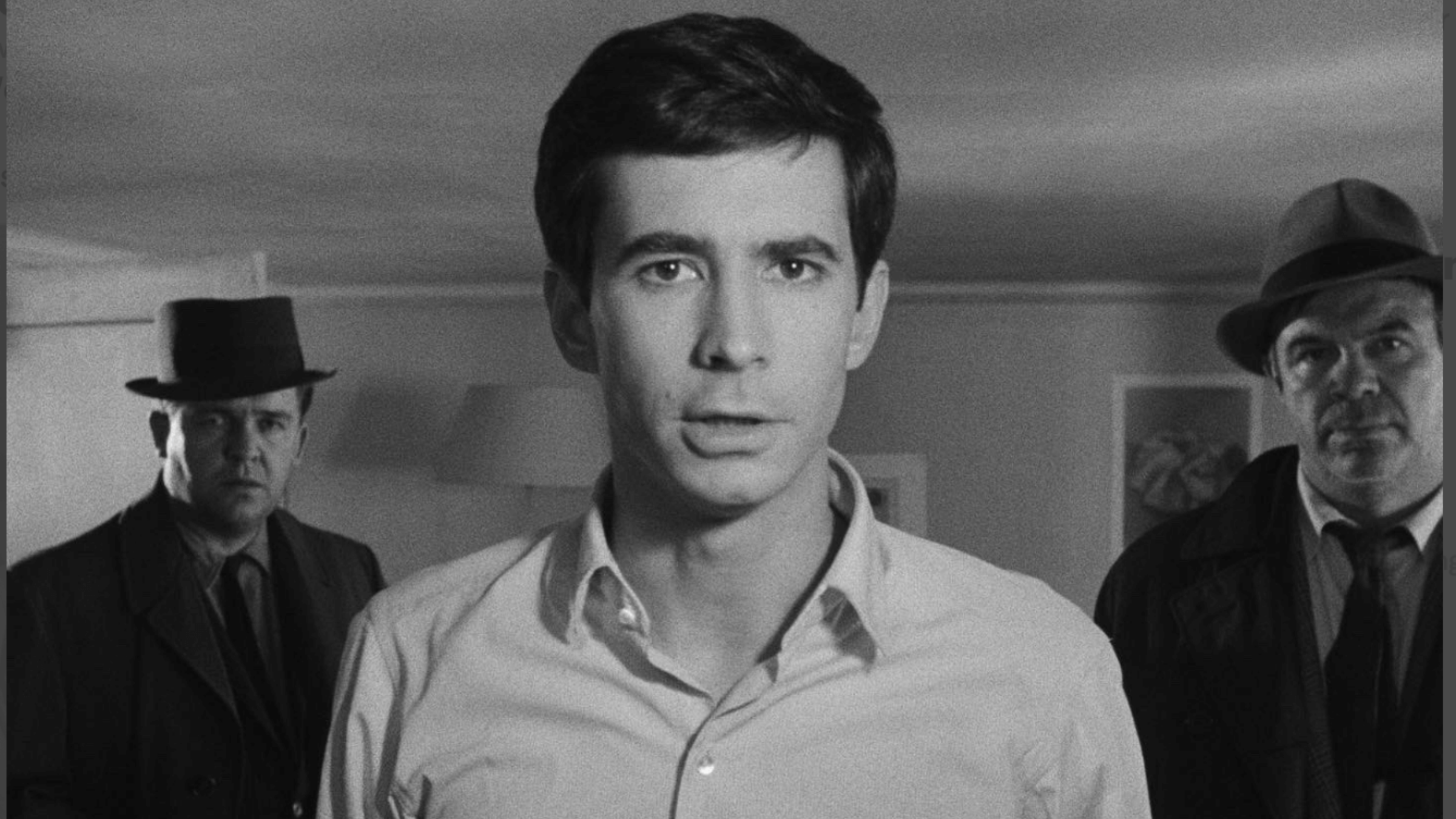

Two years after Psycho, Anthony Perkins starred in Orson Welles’ The Trial. Photo by Getty Images

Comparing a film to a fever dream is the hoariest of critical clichés (it’s right up there with calling something Kafkaesque), but some clichés have a basis in fact. The first time I watched Orson Welles’ The Trial, I was home from high school with a fever. The second time, last November, I had another fever and dozed off an hour in, though the climactic explosion woke me up just before the end titles. The third time, a week ago, I was healthy at last, not that that made any difference, since The Trial is the rare film that earns its fever dream comparisons. Almost demands them.

It was adapted, pretty faithfully, from Franz Kafka’s 1925 novel, and released 60 years ago, when Welles’ reputation in his own country was so dim he had no choice but to scrounge for financing in Europe. The story goes that his backers, Michael and Alexander Salkind, gave him a stack of books that were in the public domain, and he picked one without all that much thought (later, it turned out The Trial wasn’t in the public domain, but by then too many costs had been sunk). Still, it’s tempting to imagine that Welles — the wunderkind who woke up in Hollywood one morning and realized he’d been blackballed for some unspoken crime — had a more personal attachment to the material.

Explaining a dream to someone else, at least in my experience, is almost never a good time. You have to say what happened, of course, but you can never quite explain why it made you feel the way it did, what message your id was trying to send, which details are the important ones and which don’t matter so much. I can tell you the plot of The Trial, but not why it gets under my skin, what message Kafka and Welles were trying to send (assuming they knew), which plot points are the key ones.

A reasonable summary of the film might go like so: Josef K. (Anthony Perkins, two years after Psycho) wakes up one morning to find strange men in his bedroom. They inform him he’s under arrest but refuse to say what for. He goes to work and later the opera, where he finds he’s being pursued by other strange men. They take him to a courtroom, where he struggles to defend himself, since he still has no idea what he’s been accused of.

Josef’s uncle recommends a lawyer named Hastler (Welles), who spends most of his time in bed, talking too loudly. Sensing his days are numbered, Josef races through the city, trying to find help. He comes to a priest, who tells him he’s been sentenced to death. Executioners wrestle him into a pit and offer him a chance to do the deed himself, with a knife. When he refuses, they throw dynamite into the pit, and as they walk away an explosion swells into the sky.

Here’s another plot summary that strikes me as equally fair (and unfair): Josef K. staggers into the apartment of his neighbor, the beautiful Miss Bürstner (Jeanne Moreau). She flirts with him, but, after kissing her, he abruptly shrugs her off. At work, his boss accuses him of sleeping with his cousin. He visits the offices of a lawyer, where the wife of a courtroom guard flirts with him — he shrugs her off, too. The lawyer’s mistress, Leni, another stunner (Romy Schneider), flirts with him, and after admiring her webbed hands, he kisses her and, yet again, abruptly quits. Little girls chase him through buildings and tunnels. He finds himself in a deep pit, clutching dynamite, cackling like a madman when he should be throwing the dynamite as far as he can.

One more: Welles, past his prime and disgusted with the bureaucracies of filmmaking, watches a younger generation of movie people with a mixture of lust, envy and pity: Moreau and Schneider, the gorgeous muses of young arthouse directors, and Perkins, who was rumored to be homosexual. Sometimes he wants to mentor the younger generation, sometimes he wants to screw it, sometimes he wants to grab it by the collar, but in the end he settles for blowing it all to smithereens.

I know of no other film (nothing by Lynch, nothing by Buñuel) that conveys so vividly the sense of being in a dream — of knowing you’re in one and not being able to wake up, even. As in plenty of dreams (mine, at least), rooms are forever growing, shrinking, and changing their spots. The film was made all over Europe in the early ’60s, and Welles gets a good sense of its uneasy mix of postwar desolation, Neoclassical pomp, and Modernist grids: Scenes that seem to take place in the same room were cobbled together from footage shot in Paris, Belgrade, Zagreb, etc. Some locations that seem stable are fragmented, while others that seem different are secretly the same (most of the sets were built inside the Gare d’Orsay, the abandoned Parisian railway station that later became an art museum).

The Trial blurs the line between significant and insignificant, so that it’s hard to distinguish major characters from supporting ones, or accident from intention. The priest who tells Josef he’s going to die only gets a few seconds of dialogue, but their final exchange strikes me as the most affecting in the film: The priest calls, “My son,” and Josef whispers, “I’m not your son” (in Welles’s film and Kafka’s novel both, it’s suggested, if never spelled out, that Jewishness might be Josef’s crime). When Leni seduces Josef, there should be only two people in the room, but a third casts a shadow on the floor. Was this a mistake, or was Welles trying to literalize the point that somebody’s always watching? Does it matter?

Nothing is explained and less is solved. Characters change motivations for no reason, talk endlessly but explain nothing, meet Josef for the first time and then act like they’ve known each other for years. And yet, like dreaming a dream, watching The Trial feels entirely coherent, especially when it’s incoherent. There’s the constant anxiety of Perkins’ performance, for one, pulsing like a basso continuo beneath everything else. And Welles uses classical music to hold everything together, playing Albinoni’s “Adagio in G minor” over and over until it sounds equally sincere and sardonic, dignifying Josef’s suffering and sneering down on it. (Stanley Kubrick would pull off a similar trick with Dmitri Shostakovich’s “Jazz Suite No. 2” in Eyes Wide Shut, a film that, like Martin Scorsese’s After Hours, is hard to imagine without The Trial paving the way.)

Sixty years on, we’re left with this paradoxical thing: a perfectly chaotic, perfectly controlled work of art. It’s enough to reduce you to madness. “That’s the conspiracy,” says Josef, shortly before he gets himself blown up, “to persuade us all that the whole world’s crazy, formless, meaningless, absurd. That’s the dirty game.” It’s a paranoid thought, of course, but some paranoid thoughts, like some clichés, have a basis in fact. Are our overlords planning something elaborate and wicked, or is there really no plan at all? In The Trial, Welles cunningly splits the difference. Maybe there’s a plan and maybe not — either way, you and I will be the last to know.

Film Forum will be presenting a 60th anniversary run of The Trial starting on Dec. 8.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO