What David Crosby taught me when he kicked me out of his hotel room

In a brief encounter with the legendary artist, a lesson about journalism and artistry

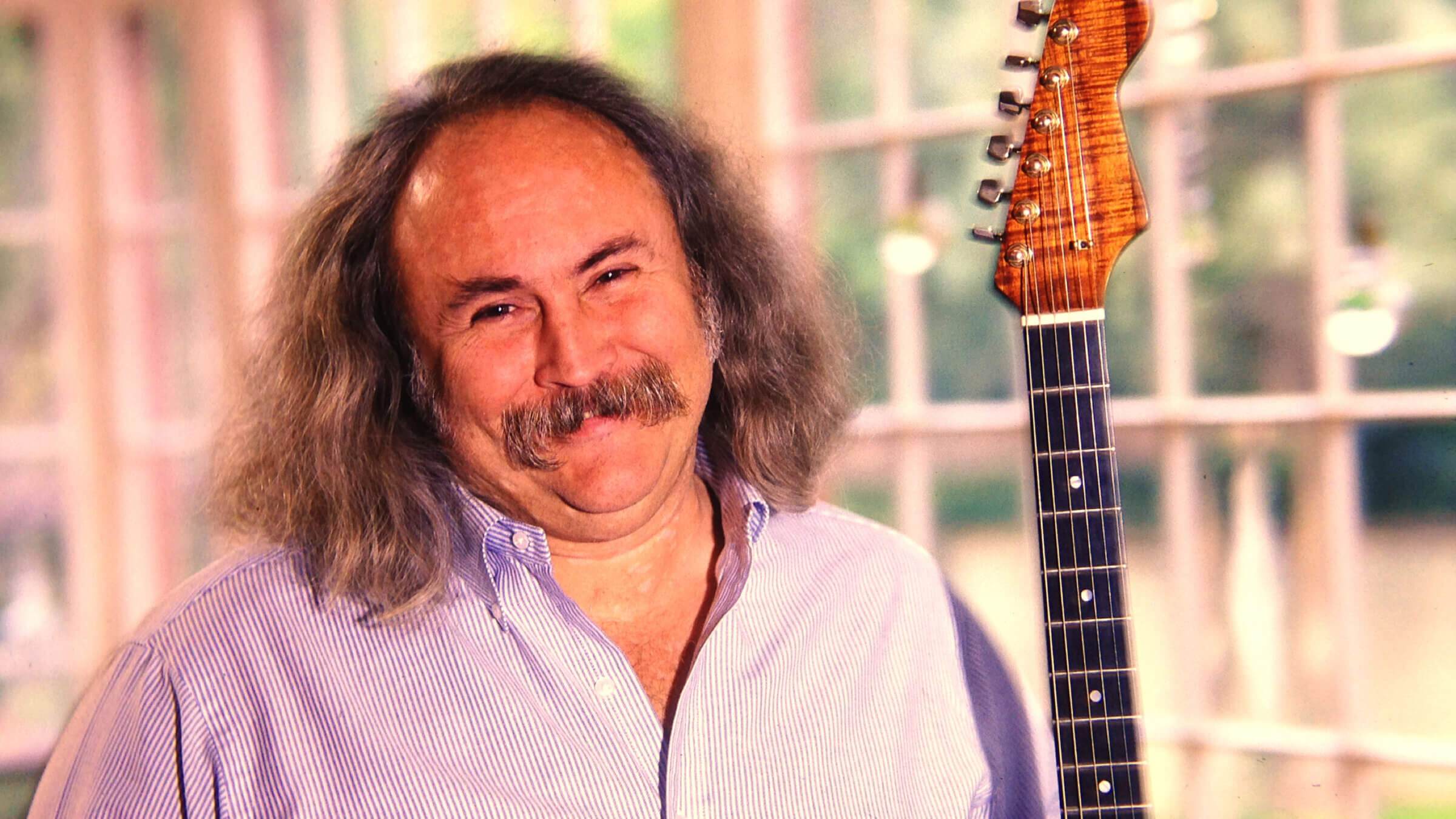

David Crosby, circa 2000 Photo by Getty Images

The call came from the publicist the day before David Crosby was coming into town. It was 1989 and Crosby was on a tour, promoting his new album Oh Yes I Can — did I want to interview him?

I was just out of college and I was freelancing a lot. I wasn’t what you might call a music journalist and I wasn’t a major Crosby fan, but I liked CSN’s performance in Woodstock, I owned a couple of CSNY albums and I certainly respected Crosby as a singer. So, I said sure and the publicist messengered over a copy of the album and Crosby’s memoir Long Time Gone, which I read “en diagonale,” as the French say.

The following day, I went to the 21 Hotel in Chicago’s Gold Coast where Crosby’s wife Jan greeted me and ushered me into the living room to meet the man. Crosby and I shook hands, his wife left the room, he sat down, and the couch collapsed, whereupon he fell into a puddle of water and stained his slacks — there’d been a leak in the ceiling that he’d already told the hotel management about.

Jan rushed back into the room, helped her husband into a chair, then left again.

I hadn’t seen enough of Crosby to know if he’d been in a foul mood before, but he was in one now. I asked him some questions about the album and he responded with monosyllables.

I asked him how writing the new album had been different from his first, If Only I Could Remember My Name. He seemed to doubt that I’d ever listened to that first one. “You actually have that album?” he asked.

“I do,” I said. “It’s in my parents’ basement.”

This was actually true, but it probably sounded like a diss. His mood didn’t improve.

I had heard a story about how Crosby used to live in Chicago’s Old Town neighborhood and palled around with a guy named John Brown who made all his capes. I asked him about Brown and whether he still kept in touch.

He said he didn’t.

We talked about his addictions, and I asked how he’d managed to kick drugs.

“I was in jail,” he said. “I couldn’t get any.”

I asked him if he thought this was one of the rare situations where the American justice system worked in his favor. He didn’t seem very fond of that idea. “Yeah, maybe that once,” he said.

Jan came back in the room to see how the interview was going.

“Just trying to help the most spectacularly unprepared journalist I’ve ever met,” he said.

If he’d said that to me today, I probably would have found it funny and would have enjoyed the opportunity to try to spar with him a bit. I would have tried to change the subject and ask him questions about his father, a legendary cinematographer who worked on High Noon and on It’s All True with Orson Welles. But at the time, I just felt defensive.

“Spectacularly unprepared?” I asked. I told him that his publicist had only sent me his album the night before and maybe if he had a problem with that, he should take it up with the publicist.

“Yeah?” Crosby asked. “Well, take your tape recorder and stuff it.”

On my way out, Jan gave me a sad smile that said this wasn’t the first time this sort of thing had happened between her husband and a journalist.

The funny thing, though, was that, even though I thought Crosby acted like a jerk, that didn’t make me like his music any less. Maybe if I’d broken a couch and fallen into a puddle and had to listen to some kid tell me my first solo album was in his parents’ basement, I’d be a little cranky too.

As always, whenever “Long Time Gone” or, later, “Lay Me Down” would come on the radio, I’d turn it up. If anything, I liked him a little more because the incident humanized him. I’d watch him stoned and grinning as he and his bandmates backed Tom Jones or listen to him beautifully harmonizing with Bob Dylan on “Born in Time” and think yeah, there’s an interesting and complicated story behind those stunning vocals, one I’d glimpsed briefly at the 21.

Getting kicked out of Crosby’s room became a funny little story to tell over drinks; it taught me about the importance of separating the art from the artist. And it taught me that, when you have chance to meet the artists you admire, sometimes — as Crosby used to say on those old anti-drug PSAs — maybe you should “just say no.”