How the Netherlands became a nation of diarists in WWII

Anne Frank was far from the only chronicler of a country’s descent into catastrophe

The Dutch World War II Nazi transit camp in Westerbork. Photo by Getty Images

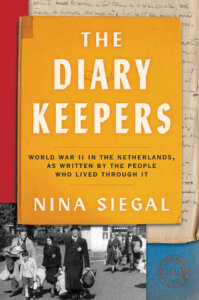

The Diary Keepers: World War II in the Netherlands, as Written by the People Who Lived Through It

By Nina Siegal

Ecco, 544 pages, $26

A diary, Nina Siegal writes, represents a “first draft of memory.” Shaped by circumstances, ideology and intent, it remains distinctive from later testimonies in its immediacy and inability to foretell its own ending.

Those factors surely contributed to the power of one of the Holocaust’s preeminent literary artifacts, The Diary of Anne Frank, by a German Jewish adolescent on the cusp of life, and of death, in her secret Amsterdam annex.

In fact, as we learn from Siegal, an American journalist and novelist also residing in Amsterdam, the Netherlands was a nation of World War II diarists. Immediately after the country’s liberation, the new NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies put out a call for first-person accounts. Thousands flooded in, and the institute continues to transcribe and digitize them.

In The Diary Keepers, Siegal, whose Czech-born maternal grandfather survived the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria, uses a handful of those diaries — carefully chosen, translated, edited and arranged — to describe the German occupation of the Netherlands and events leading to the murder of three-quarters of the country’s Jewish population. She intersperses the diary entries with fragments of her own family narrative, as well as essays on the period, the diarists, the problem of historical memory, and the Netherlands’ attempts to wrestle with a heritage of both rescue and complicity.

Siegal’s most surprising decision is probably the inclusion of journals from two avowed Dutch Nazis, alongside those of more sympathetic diarists. One of the Nazis, the brutish police detective Douwe Bakker, frets about his career, admires Hitler, and exults in the persecution and deportation of Jews. Another journal contains the short jottings of the pseudonymous Inge Jansen, the wife of a Dutch Nazi official, who revels in the perks of Nazi social life. (Dutch law, Siegal notes, bestows privacy on the descendants of collaborators.)

Neither journal has much literary merit. But, juxtaposed with other entries, they serve as ironic counterpoints to the tribulations of more admirable and eloquent diarists, variously in hiding, imprisoned in the Westerbork transit camp, or subject to arrest for resistance activities. Siegal’s goal, she writes, was to offer “a range of perspectives,” as well as “to explore gray zones, territories of moral indecision and moments of social collapse.”

Siegal organizes the selected passages, mostly from just seven diaries, into a chronological narrative of the besieged Netherlands, and especially the fate of its Jewish population. Her own writing is smart and on-point. One minor complaint: Sometimes she offers biographical information only retrospectively, following journal entries that might have benefited from an introduction.

In addition to the task of editing and, with some assistance, translating the diaries, Siegal has done her journalistic due diligence. She visits key locations and talks to historians, relatives of the diarists, and others. A few potential interviewees, not wishing to revisit painful memories or family history, decline her overtures.

Remarkably, though, Siegal makes it to Israel to interview 105-year-old Mirjam Levie, once a secretary to Amsterdam’s controversial Jewish Council. Levie’s (previously published) diary is a compendium of unsent letters to her fiancé, Leo Bolle, whom she would later marry. Among its most memorable passages is an account of her exhilarating journey, in the summer of 1944, from the horrors of Bergen-Belsen to freedom in Palestine as part of a group of Jews exchanged in a prisoner swap. “We are living a fairytale,” she writes.

Levie’s earlier reflections afford insight into the dilemmas of the Amsterdam Jewish Council, which tried to mediate between murderous Nazi demands and an increasingly threatened Jewish population. In the end, that effort proved an embarrassing and catastrophic failure, but, in Siegal’s interview, Levie expresses no regrets about her modest role.

Also notable are the writings of Philip Mechanicus, a journalist imprisoned in Westerbork, and Elisabeth van Lohuizen, a religiously motivated resister who hid Jews in her hometown of Epe.

After the Nazi invasion, Mechanicus continued writing for a newspaper under a pseudonym until mounting antisemitic pressure led to his firing. At Westerbork, he became a keen observer of camp life, “an unofficial reporter,” he writes, “covering a shipwreck.” He analogizes the camp’s Jews to “Job on the dungheap.” At the same time, he pauses to admire the beauties of the landscape and envy the freedom of seagulls in flight. And he writes, philosophically: “Space and time have dissolved. One lives against a backdrop of nothingness.”

Thanks to his protectors, Mechanicus managed, for 17 months, to dodge the camp’s most terrifying aspect: weekly transports to Auschwitz and other Nazi concentration camps. The reprieve was both rare and not long enough.

Van Lohuizen, an acolyte of the Liberal Dutch Reformed Church and the owner of a general store, emerges as an uncommonly brave soul. She and her resistance organization lodged Jewish refugees in safe houses surrounded by forests. Betrayal was a constant threat. “The tension,” she writes, “is sometimes too much to bear.” Along with her husband and son, she was arrested at least twice for her activities, but was released and survived the war.

Siegal’s most interesting essays include her explorations of the role of the Amsterdam Jewish Council, and of what historians call “the knowledge question” about the Holocaust. How culpable was the council for cooperating with the Nazi invaders, she asks, and how much did the broader Dutch population know, and believe, about the slaughter of Dutch Jewry? The answers turn out to be complicated.

The Netherlands’ postwar handling of Holocaust memory generated what one theorist called “a mythscape,” Siegal writes. An early, clumsy attempt at a memorial, in 1950, was the so-called Gratitude Monument, meant to thank the Dutch for their solidarity and rescue of Jews. It was only in 2021 that Daniel Libeskind’s National Holocaust Names Monument finally commemorated the 102,000 Dutch Jewish lives lost. A National Holocaust Museum is now slated to open in 2024, eight decades after the disaster.