How Jane Eyre and Marvin Gaye helped to inspire a pop star’s debut novel

With ‘This Bird Has Flown,’ Susanna Hoffs, formerly of The Bangles, explores her literary side

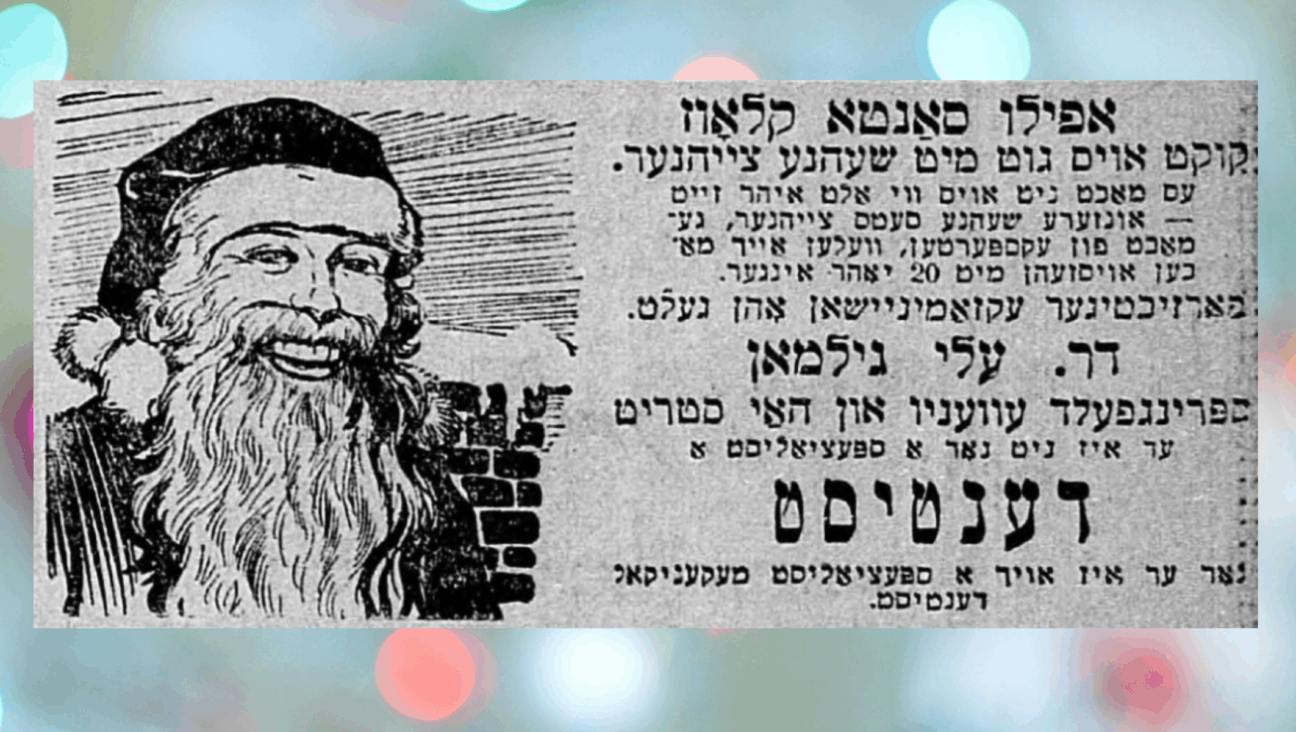

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The parallels between Susanna Hoffs and Jane Start — the protagonist in Hoffs’ forthcoming debut novel This Bird Has Flown — are initially quite striking. Both are creative, well-educated women brought up in Los Angeles by artsy Jewish parents. Both had massive success as recording artists during their 20s, only to find the music business far less receptive to their work a decade later. And both enjoyed major hits with songs penned by legendarily reclusive and controlling rock stars.

But there the similarities end.

The novel takes place in the present day, which means that 33-year-old Jane would have been born shortly after Hoffs and her bandmates in The Bangles went their separate ways in 1989. Jane has also always been a solo artist, and her lone hit is remembered as much for the pink wig she wore in its video as for her radical reinterpretation of the source material. And instead of being happily married for three decades to a famous filmmaker (as Hoffs has with Jay Roach), Jane is desperately trying to regain her equilibrium after being unceremoniously dumped by her director boyfriend for the star of his latest film.

These subtle sorts of twists on reality are part of what make This Bird Has Flown such an entertaining read. Hoffs’ novel is grounded in a world she knows all too well, and can thus paint in fascinating (and at times horrific) detail. But the story is more charming rom-com than cynical roman à clef: A chance encounter on a transatlantic flight leads Jane into an unexpected romance with a professor under the gleaming spires of the University of Oxford, though their new love is as imperiled by the sudden demands of her newly resurgent career as it is by the secrets that they are both keeping from each other.

Yes, This Bird Has Flown is a little like Bridget Jones’ Diary (With Guitars!), but there’s nothing wrong with that. (Universal Pictures, which has already snapped up the film rights to the novel, clearly agrees.) Hoffs’ writing is extremely witty and engaging, and she brings eccentric Oxford professors and wealthy British playboys to life with the same affectionately vivid strokes that she applies to battle-scarred veterans of the music biz. Go ahead and put it on your “Beach Reads” list for this summer …

Hoffs, who also has a new album of cover songs coming out April 7 — The Deep End, produced by the legendary Peter Asher — talked with me about This Bird Has Flown.

How did this novel come about, and what inspired you to write it?

Well, it really was kind of a lifelong dream to write a novel. I had not started in earnest, but I have a couple of handwritten notebooks with the beginning of something, and the date on those notebooks is 1989. So, those would have been written right as the Bangles thing was kind of — well, how would you describe it? It was a crazy, fast and furious run during the 80s, but I remember towards 1989 we were all tired and exhausted. It’s hard to just kind of live your life in a van or a bus, where you’re constantly with the same people and you have very little autonomy in your life. So, I knew back then that I wanted to do this, but honestly, I’ve always been a reader my whole life. I love being lost in a story; it’s an excuse to be out of my own head.

But one day, several years back, I had been working on a screenplay and it looked like it was going to be a situation where — though I’d put a year and a half of my life into it, and worked with one of Jay’s writing partners on it with the idea that it would be something for Jay to direct — it sort of stalled out, like these things do. And my older son Jackson said, “Mom, why don’t you write a novel? You’ve always talked about it.” And I thought, “Yeah, why don’t I? It wouldn’t be that different from what I just experienced on this screenplay, except that I would be doing it alone.”

In all the years of writing songs, I almost always collaborated. So this was a brand new adventure, deciding to do a solitary project for myself. And the way that it sort of unfolded was just this wonderful, joyful experience.

Was Jane Start, the story’s protagonist, always going to be a singer-songwriter?

The original opening was sort of different than it turned out being in the book, but it was a similar kind of idea. I thought about, “Should she be an actress?” I knew I wanted to take on a protagonist who was a performer in show business in some form or fashion, because it’s something I know. But then I realized that this was an opportunity to kind of explore this sort of unspoken experience that I’ve had, to try to figure out how to find the words to describe it from the inside out.

You capture the less-than-glamorous aspects of musician life quite vividly.

Thank you. When people ask me, “What’s it like being in a band?” I say, “Watch Spinal Tap!” [laughs] I feel like they got it so right, because everything that can go wrong will, whether it’s actual technical difficulties or there’s just “complexity” with the various players involved with the performance. And there’s such a wide range of performance experiences — I mean, that’s why I wanted to start the book with Jane performing at the private bachelor party, because there’s this whole world of private gigs that’s not really ever spoken about, like where billionaires on islands pay famous artists to play their parties.

But it’s all music; it’s all entertainment. There’s that part of it, and then there’s the “being an artist” part — trying to write or create something that’s lasting or connects you with other human beings, or has beauty to it, or has angst to it or whatever it is. You’re trying to create music that connects, but you never know which thing will. And in the case of Jane Start, she covers this lesser-known song by an artist that she loves — Jonesy, this kind of mythic, iconoclastic artist — and does a dramatically different spin on it. She just kind of throws it out there, but then she’s totally pigeonholed for doing that. It’d be like if “Walk Like an Egyptian” became the one thing that The Bangles were known for.

Or “Manic Monday.”

Exactly. There were periods of time when I was working on the book, where I only focused on how this is a brokenhearted girl who feels like she’s washed up and will never have a way to be impactful as an artist, or connect with an audience or anything. There’s the fish out of water story of her in England, and this sort of first flush of romantic love, because that was endlessly fun to write about. And then there was the dark side of this character grappling with whether she can still contribute anything as an artist; she has such low confidence after a bit of hard knocks in her life, experiencing all these rejections and failures. So there are these two journeys that she’s on.

Have there ever been periods in your own life where you’ve felt like Jane does about her career?

Oh yeah. All the time. Like, yesterday! [laughs] I just put out a new single [a cover of The Rolling Stones’ “Under My Thumb”], and I don’t even know what you do with the music business now. I had years of being on record labels and then years of not being on record labels; and really, except for the period when [The Bangles] were at Sony, I’ve always considered myself an independent artist. I self-financed the new album that I did with Peter Asher, who is a producer I revere, and I was “indie” in how I went about writing the book.

I didn’t sell it with just a chapter or something; it took some coaxing from my agent before I felt like the book was finished enough to even send it out to publishing houses. Even before The Bangles started, I was putting flyers out looking for bandmates; I left flyers at the Whisky A Go-Go at a Go-Go’s show [laughs], and that was how it started. The Bangles began as a very indie band, and I still feel most comfortable that way, to be honest.

Though Jonesy’s physical attributes are very different, it’s hard not to read some elements of Prince into his controlling and inscrutable behavior, as well as his transcendent performances.

Yeah, well, he’s a character, like all the others from my imagination. I was really into the show Peaky Blinders, and Cillian Murphy was how I sort of pictured the genius rockstar — something about the sort of childlike face and the freckles and the blue eyes. But during the course of my years in the music, I have witnessed a number of performances by artists that almost are supernatural in their talent, you know? I mean, everything from watching Robert Plant to when we opened for Cyndi Lauper; we were on so many stages and festivals with such talented people.

There’s a moment in your novel where Jane is invited to join Jonesy’s world tour. It would be great for her career, but it would also force her to give up any sense of independence for seven months — and the sense of existential dread she’s feeling about making that commitment really comes across.

Oh yeah, I’ve actually felt that — I toured a lot with the band, and I definitely used those feelings for the scene — but I also based that scene on Jane Eyre, which was such a great tool in crafting the structure of the book. In Jane Eyre, she’s asked to make this decision whether to spend her life as a missionary’s wife — she would have to go with him on a trek to India for seven years, I think — or does she follow her heart and find Mr. Rochester again? And I identified with Jane, and I identified with that feeling of repetition; somewhere inside of her, she knows that if she just keeps repeating the one thing she’s known for, and is never able to break away from that mold of how she’s been stereotyped, it will become who she is. I don’t want to give too much away to your readers, but it’s really cool that you pointed out that moment, because it was really emotional for me to write it. Like, tears were streaming down my face as I was writing it. [laughs]

Setting the story in England — was that a nod to Jane Eyre as well?

Yeah — I loved the whole idea of a gothic setting in a modern novel, like Manderley, the giant mansion in Rebecca. And Oxford, where Jane’s love interest lives, provides a great setting for this fish out of water story, because it’s so different from Los Angeles, where she’s from. So the gothic element in the story is city of Oxford, and even England to some extent. There was a whole version of the book where she kind of limps back home to LA, and it was kind of cool. But at the end of the day, I wanted to keep her in Europe and then I wanted to have her go to the south of France — that was just fun because I always think of Keith Richards and all those great Rolling Stones pictures at Nellcôte.

How important were those kind of visuals to your writing process?

I had a mood board for the whole book, trust me. I had “casting pictures” for the characters. Because they were mostly designed in my brain, but sometimes I’d be like, “Hmm, would it be fun to just look at and stare into this face of this person, and find words that will describe them.” You know, I really didn’t know what I was doing. I just kept reading books and revisiting books that seemed thematically valuable to learn from. It’s like playing guitar, when I was younger, just saying to friends in the schoolyard, “How do you play that chord?” Maybe it’s laziness, but I’ve always just been about doing the self-taught thing.

And obviously, music had to have played a big part in your writing.

Oh yeah. I mean, songs informed everything. I made all these playlists for it, and the characters would just start talking as soon as I was listening to a song. And then, when I realized that songs could be chapter headings, it was like, I could do as much as I could with songs, because songs were driving the writing. Like, Marvin Gaye’s “Sexual Healing” — I would put on that song and be like, “OK, we’re in Oxford and this is the new love.” And like, how perfect is that song? It’s so sassy; I love it.