‘When did you learn your grandfather was a Nazi?’ — Burkhard Bilger’s redemptive journey through a complex family history

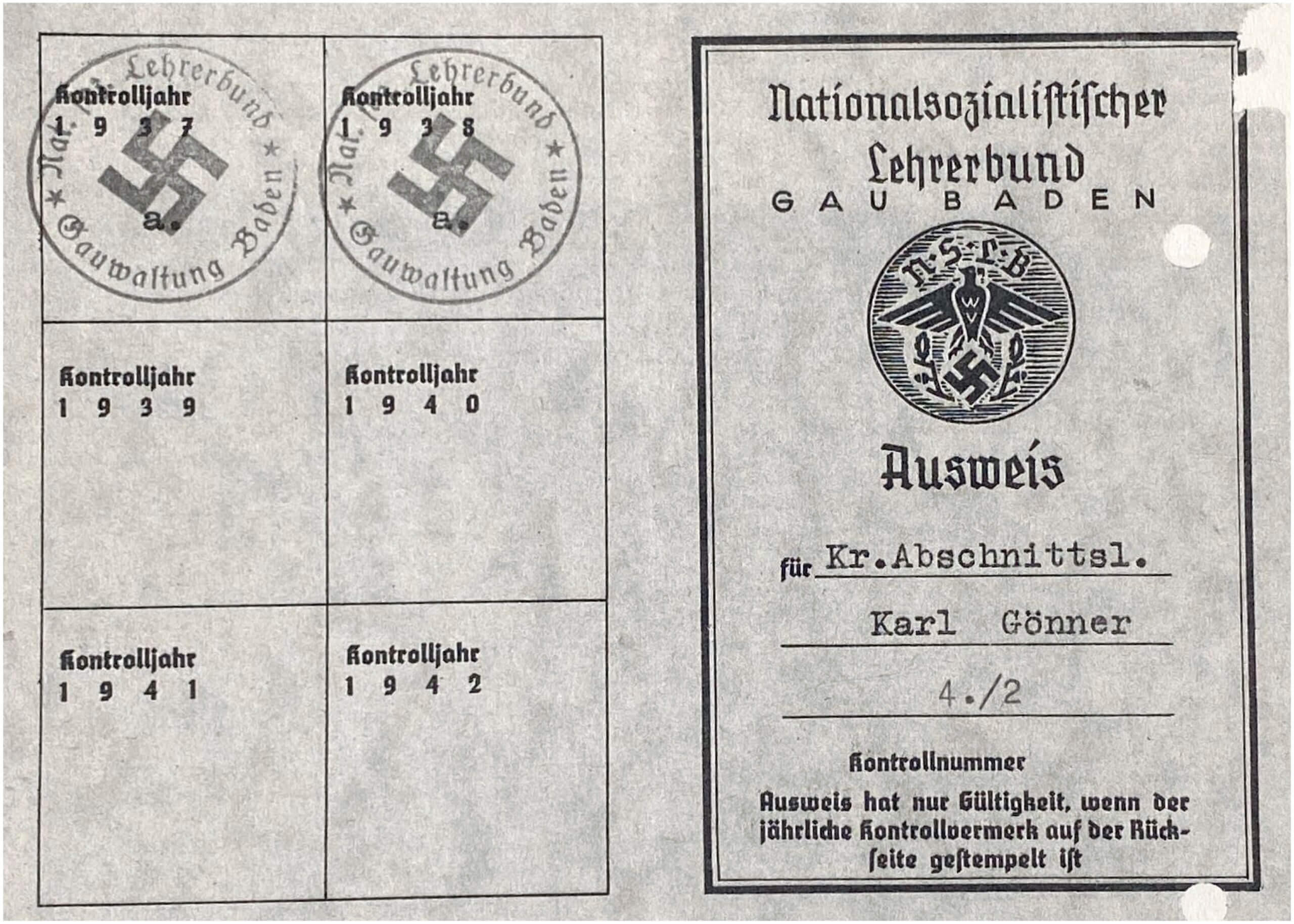

In ‘Fatherland,’ the acclaimed New Yorker writer considers the case of an elementary schoolteacher named Karl Gönner

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

In his new memoir, Fatherland, Burkhard Bilger poses a provocative question: What do we owe the past? This question is especially poignant when the past brings to light uncomfortable revelations about our family history.

Fatherland delves into the complicated legacy of Bilger’s maternal grandfather, Karl Gönner, an elementary schoolteacher from the Black Forest who held a leadership role in the local branch of the Nazi Party during the occupation of France where he organized events and promoted Nazi ideology. In the memoir, Bilger reflects on this family history and grapples with personal legacy, guilt and forgiveness.

Bilger and I have been friendly since just after the millennium when I read his essay collection Noodling for Flatheads, a fun, breezy book in which the Oklahoma-born author took readers on a tour through lesser-known Southern subcultures, relating stories about coon hunting, catching catfish with your hands, frog farming and moonshining, all told with a sharp wit and an eye for the absurd.

In late 2000, I was raving about the book at the offices of Discover Magazine where my friend, who worked as an editor there, stopped me mid-sentence to tell me that Bilger was just down the hall, working on a koala story. “Hey, Burk!” he called out. “My friend was just saying she digs your book.”

Not long afterwards, I bumped into Bilger on the F train; he told me he had been hired as a staff writer at The New Yorker, where he still works. Bilger’s widely acclaimed writing style, which he has perfected there, involves delving into the stories of unusual individuals such as the short-order cooks of Las Vegas and a cheesemaking nun, and is characterized by his ability to connect with his subjects.

He worried: How would readers react?

Bilger and I met at the Condé Nast cafeteria on the 35th floor of One World Trade Center to discuss Fatherland. Looking out the window at the Hudson River, the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, I couldn’t help but think about my Jewish grandparents, who fled antisemitism and arrived in America before the clerks at Ellis Island started processing paperwork. It felt a little surreal to be sitting across from the enlightened grandson of a Nazi leader.

Bilger is 59 years old. This was the first time I’d seen him since the pandemic and his thick brown hair had become a shock of white. I asked him to describe himself the way he might write in a New Yorker profile.

He grinned. “His downturned eyes and gap in his teeth are two of his most distinctive features. His flexible face can make animated expressions, but his resting face is stern,” he said.

We both laughed hard.

Fatherland, I told him, was unlike anything I had read of his before (and I read everything he writes). He agreed that the book was a significant departure. In his previous work, he said, he had always played the role of Sancho Panza in the Don Quixotes he covered. “If I pop up at all, it’s for occasional comic relief,” he said. Turning his attention to his family history for the first time forced him to write in a different and more introspective style, which was a hard slog.

I asked him why the book took so long to write, then apologized. “Is that too insensitive?” I asked.

“Not at all!” he said. “As a magazine writer, I’m used to working with tight deadlines, so initially, I thought it would take me three or four years to complete. Oh, this embarrasses me now, even saying that! But I quickly realized I wanted to approach it with a level of detail that took me nine years to fully achieve.”

I asked if he worried about how people would react learning about his family’s history or if he put that out of his mind while he was writing.

“Man, I worried terribly!” he said. “When I started working on Fatherland, I was concerned about how readers might perceive me and my intentions. I was concerned about being seen as an apologist for my grandfather’s actions. I knew that for readers to trust me as a narrator, they needed to believe that my heart was in the right place and that it was imperative to show that I was not trying to whitewash my family history or downplay the horrors of the Nazi regime.

“Finding that balance was a challenge. I wanted to acknowledge the complexities of my grandfather’s character and actions and condemn his involvement in the Nazi party. It was a delicate line to walk. I worried about offending readers. In the end, I believe I conveyed my honest feelings about the situation while also acknowledging and respecting the suffering of the victims of Nazi rule.”

Before he learned about his grandfather’s history, Bilger said he knew Karl Gönner mostly as an old man with a glass eye in a German nursing home and whom he visited on childhood visits abroad.

“When did you learn that your grandfather was a Nazi?” I asked.

He sighed.

“Yeah, a biggie, right?” he said. “I found out about his war crimes trial when I was 28, that back in 1946 he was being tried for the murder of a farmer named Georges Baumann. But I first learned about his membership in the Nazi party back in high school.”

High school was in Oklahoma, where Bilger’s father, Hans Bilger, was a physics professor at Oklahoma State. I asked if his fellow students in the American heartland ever made fun of him for his name.

He smiled. “What do you think? Brickhead Belcher!” he said. “We went to Germany for a year when I was 4 and 5, so I came back, and I started first grade in Oklahoma, and my first week, my mother dressed me in lederhosen.” He effortlessly shifted to an Oklahoma accent, “What the hell is that boy wearing?”

“In the beginning, we absolutely stood out,” he said. “I remember my mother would come to PTA fundraisers and make some strange German dessert; she had this extreme German accent. But when my mom went back to grad school in 1974, we started eating like Americans. She got that Pillsbury Bake-Off crescent roll kick.”

From a young age, Bilger was immersed in multiple languages, learning English and German simultaneously, and French during a family sabbatical in Montpellier, France, during sixth grade when he was enrolled at a local school, which helped with the reporting and writing of Fatherland. Speaking local dialects allowed him to put his subjects at ease when he was conducting interviews with elderly men and women in German and French villages.

Although Bilger’s mother earned her Ph.D. in history with expertise in Germany, she rarely talked about her father’s connections to the Nazi party or his role in World War II. Bilger first learned of a more tangled history when, in 2005, his mother received a yellowed packet of letters from a relative in Germany, written in a strange cursive, from villagers in Alsace who had testified on behalf of Bilger’s grandfather just after the war. They had been found in his grandfather’s desk.

The letters offered conflicting testimonies about Karl Gönner, painting him as both a savior and a tyrant. One letter accused him of ordering police to beat a local farmer to death. Was he a war criminal, Bilger wondered, or a man doing his best in the face of an unfathomable regime? The more he learned about his grandfather’s story, the more he found himself uncovering complex truths about his family’s past.

In early drafts of Fatherland, Bilger took a novelistic approach, at times delving into his grandfather’s thought process and writing his internal monologues. Two colleagues at The New Yorker — David Grann, who had Jewish relatives killed in the Holocaust, and Raffi Khatchadourian, who lost relatives in the Armenian Holocaust — advised him to pull back on that approach, for fear that he might appear to be defending his grandfather. They advised him to focus on presenting the facts and letting the record show what he learned.

But even with this refinement, he struggled to find the right balance between acknowledging the complexities of his grandfather’s character and actions and condemning his involvement in the Nazi party. As he says of his mother, at the end of Fatherland: “She came to think of [her father] as a soul undone by history and then spared by it — a man whose reckless, blinkered idealism led him to the Nazis, then gave him the nerve to resist them. “‘Angst het er nit g’ha,‘ she told me. Fear wasn’t in him. But she could never truly forgive him.”

‘History can be redemptive’

For Bilger, Fatherland isn’t about blaming a particular community, but rather taking responsibility for addressing broader issues. He rejects black-and-white thinking and instead presents a nuanced exploration of the humanity of everyone involved. This challenges readers to recognize the potential for violence and prejudice in all societies, not just in well-known examples like Germany, Russia, China and Rwanda, but in the United States as well.

Although he considers himself agnostic, Bilger says he has found solace and community within the Old First Reformed Church, which he joined on his wife’s suggestion. The Park Slope church’s sermons and parables provide Bilger with opportunities to reflect on moral issues, mysticism and life’s biggest questions.

Through his introspective approach, Bilger encourages readers to confront uncomfortable truths about their family histories and the importance of historical memory. His words remind us that vigilance and self-reflection are key to building a more compassionate and just world. The legacy of the past can continue to shape the present if left unexamined, and Bilger’s work encourages us to engage in the vital work of self-examination.

“History can be redemptive,” he notes. “It doesn’t have to be a burden; it can be a gift.”