It was a pioneering trans library — until the Nazis burned it

In Weimar Germany, the gay Jewish doctor Magnus Hirschfeld performed the first gender-affirming surgeries and collected research on sexuality. The 1933 book burnings destroyed his life’s work

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Just a few months after Adolf Hitler became Germany’s chancellor, pro-Nazi university students celebrated the nascent Third Reich by organizing public book burnings in 34 German towns and cities. These ceremonial destructions of “un-German” texts, often accompanied by parades, concerts and speeches, were carefully documented by Nazi officials and are now symbolic of the country’s descent into fascism. Some of the core images associated with the Holocaust show piles of books smoldering in the streets of Berlin, and the new regime’s antipathy for Jewish authors like Heinrich Heine and Max Brod is now well-known. But another category of literature that perished in the book burnings — troves of research on sexuality — goes largely unnoticed today.

One of the institutions ransacked by the Nazi student groups that organized the book burnings was the Institute for Sexual Research (Institut für Sexualwissenschaft). Founded by the pioneering sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, the institute was the first medical center devoted to the study of gender and sexuality. At the institute, trans patients received gender-affirming care, activists campaigned for the rights of queer Germans and doctors conducted research on gender-affirming procedures — much of which was lost forever in the book burnings.

Today, the United States is experiencing a moral panic about transgender rights, with attempts in many states to ban gender-affirming care and public expressions of queerness. Meanwhile, book bans are proliferating across American school districts, with activist parents agitating to remove books about marginalized groups and the United States’ long history of racism. Suzanne Nossel, the CEO of the free expression organization PEN America, described the book bans as a “relentless crusade to constrict children’s freedom to read.”

Comparisons between Weimar Germany and the current American political climate are often simplistic. But historic campaigns against transgender people and efforts to limit access to literature can inform us about the implications of such attacks today. Here’s an introduction to the Institute for Sexual Research, its radical vision and its tragic demise.

Who was Magnus Hirschfeld?

Born in 1868, Hirschfeld was a gay Jewish doctor, sexologist and activist. At a time when the medical establishment pathologized homosexuality, treating it as evidence of mental illness or moral degeneracy, Hirschfeld argued that queer people were acting “according to their own nature” and should be respected as such. He coined the phrase “sexual intermediaries” as an umbrella term to describe any person whose gender or sexual identities did not conform to cisgender, heterosexual norms, identifying Socrates, Michelangelo and Shakespeare as famous historical examples. Even more radical in the context of his own era, Hirschfeld also recognized that some people have no fixed gender identity.

In 1897, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, one of the first gay rights organizations. The group adopted the motto “Through science to justice,” reflecting Hirschfeld’s belief that if Germans could be persuaded that homosexuality was a biological trait, they would relinquish their prejudices. He lobbied against “Paragraph 175,” the section of Germany’s legal code that criminalized homosexuality.

Hirschfeld’s concerns were not limited to the rights of gay men. He also gave sex advice to heterosexual couples and argued for wider access to birth control. On lecture tours in America, his wide-ranging expertise earned him the nickname “the Einstein of sex.” He even played a fictional sexologist in the 1919 film Different From the Others, about a gay violinist who dies by suicide. The cameo was a testament to his reputation in Berlin’s gay community.

In order to put his ideas into practice, Hirschfeld founded the Institute for Sexual Research in 1919.

What did the Institute for Sexual Research do?

Housed in a gracious Berlin mansion, the Institute for Sexual Research offered medical care and education on issues like venereal disease, pregnancy and fertility. Hirschfeld, who lived in an apartment above the institute, performed the first male-to-female gender-affirming surgeries in 1930.

Hirschfeld also worked to protect his patients from the indignities of life in a hostile society. When some trans women could not find work after surgery, he employed them at the institute. And although his efforts to decriminalize homosexuality were unsuccessful, he procured “transvestite” identity cards for his patients, a stop-gap measure that helped them live openly as women without being arrested.

Besides serving patients, the institute housed offices for feminist activists and a printing press for progressive sexual health journals. The institute regularly hosted lectures and film screenings. Hirschfeld and his colleagues also developed an enormous library of rare texts and notes on gender-affirming surgery.

Why was all this happening in Berlin?

While the most famous and successful gay rights movements occurred in the late 20th century, historians have argued that the first attempts to gain public recognition for queer people took place almost a hundred years earlier in Germany. In 1867, a year before Hirschfeld’s birth, a lawyer contended before a German legal body that the government was punishing queer people for desires that “nature, mysteriously governing and creating, had implanted in them.” In 1869, an Austrian thinker coined the term “homosexuality” (in German, Homosexualität).

In the early 20th century, Berlin’s queer bar scene was famous enough to earn mentions in tourist guides. The city provided a safe haven for gay people from less hospitable countries. The British writer Christopher Isherwood, who lived in the city from 1929 to 1933 and whose work inspired the musical Cabaret, summarized the city’s vibe succinctly: “Berlin meant boys.” So while Hirschfeld was thinking far ahead of his time, he also worked within one of Europe’s most empowered queer communities.

How did the book burning happen?

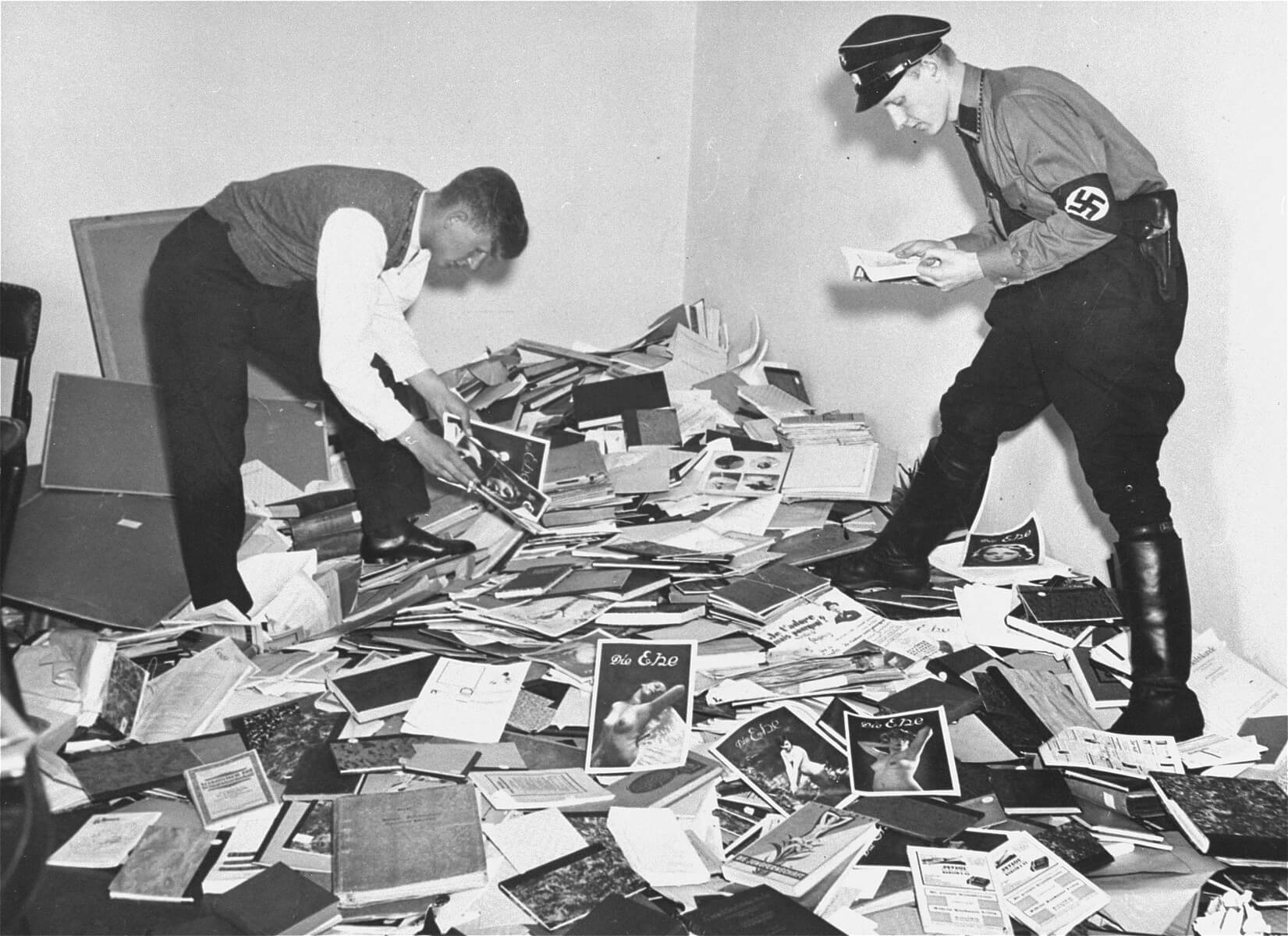

In 1933, after Hitler was elected chancellor, the government began to purge cultural institutions of “degenerate” art and the artists who produced it. Third Reich propagandist Joseph Goebbels drew on pro-Nazi student organizations for help in this project. In April, the Nazi German Student Association proposed an “Action Against the Un-German Spirit” that would culminate in a series of book burnings.

Students broke into and occupied the Institute for Sexual Research on May 6. Four days later, they burned its entire library, along with thousands of other “un-German” books. University students accompanied the burnings with torchlight processions.

Hirschfeld, who was working in Paris when the institute was ransacked, learned of the library’s destruction through a newsreel and never returned to Germany. He stayed in Paris until the threat of a Nazi occupation caused him to flee to Nice. En route, he died of a stroke on his 67th birthday.