‘My head was exploding — how could one woman do this to another woman?’

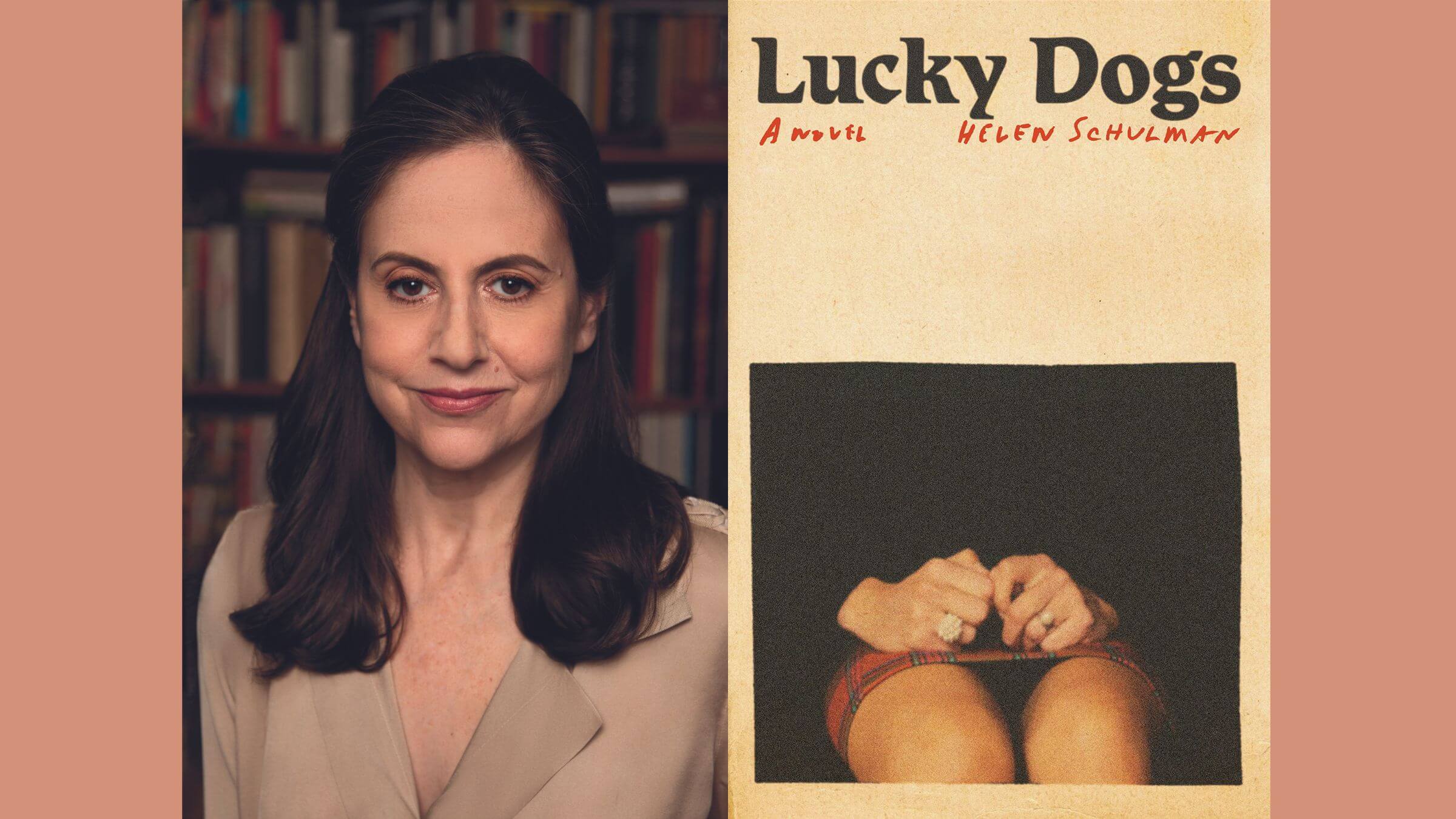

Helen Schulman explains the intersecting lives and shocking betrayals in her latest novel ‘Lucky Dogs’

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Over Zoom, Helen Schulman looks much the same as when I met her nearly 30 years ago at BreadLoaf Writers Conference. She was only 28 then, but already she had published her first book, a collection of stories, Not a Free Show, in 1988, and was teaching in the graduate program at Columbia University.

Since then, Schulman has gone on to publish eight works of fiction, including P.S., her magical novel about lovers impossibly reunited, which was adapted to a film of the same title in 2004, starring Laura Linney. Schulman’s newest book, Lucky Dogs, might be her finest novel yet. It introduces us to two women, Meredith (Merry) and Nina, whose disparate childhoods bring them together in Paris where Merry has gone for respite from Hollywood and the fallout from her assault by an infamous film executive. But the novel doesn’t just move in the compelling and intricate present; Schulman takes us into these women’s complicated and intersecting lives, and their shocking betrayals of one another.

We travel from Paris, to Sarajevo, to Tel Aviv and LA, on a riveting, immersive, and complex journey that is not easy to put down or forget. With the publication of her previous novel Come with Me, which examines the perils of technology and Silicon Valley, and her 2011 novel, This Beautiful Life, that looks at the perils of the internet and how it can explode family life, Schulman has established her place as one of the most astute chroniclers of how Americans live. I talked to her about what brought her to her newest novel and the way she is able to weave, with precise and elegant prose, the novelist’s weapon, her curiosity and deep concern about the global world and its history, with the haunted contemporary world.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Tell me a little bit about why you wrote Lucky Dogs.

I was reading so much about #MeToo and my head was exploding. I came across this piece of information, which was that on behalf of Harvey Weinstein, his lawyer, David Boies, went to Ehud Barak, who was the former prime minister of Israel, to find a spy to discredit Rose McGowan, the actress. She was writing a book and she was tweeting about Harvey, and so, Barak told Boies to go to Black Cube, an Israeli spy agency, full of ex-Mossad agents. The agent assigned to the Rose McGowan case was a woman who, as a child, lived throughout the siege of Sarajevo. Her family was airlifted to Israel because her great-grandfather had protected Jews during World War II and had died for it. That family he saved emigrated to Israel and later when they heard about the siege of Sarajevo, they petitioned the government to airlift them out. They became Jews.

I was stunned because I was thinking about Bosnia and civil war, as America was really on the verge of civil war. And I was thinking about Israel because Israel is always in a state of civil war. And then when I read this, I thought, oh, my God! It’s women in a civil war against each other. When I saw this story I just felt I was on fire. How could one woman do this to another woman? How could a woman re-victimize a woman of sexual assault for money to destroy her? I had to write my way to understanding. And that’s why I wrote the book.

Both women have been in a war, haven’t they. Why did you choose to write Meredith, who seems to be an amalgamation of many actresses, including Rose McGowan, in first person, so close in her thoughts, whereas Nina is written about in the more distant third person?

I feel very close to Meredith. She’s only 24, and I could relate to her feelings of anxiety and depression and loss and pain. I’m pissed off about how sexualized girls are. I grew up in the ’70s. We were like, we’re not wearing makeup. We’re into our own careers. And then I have a daughter, who, when I take her to find a bat mitzvah dress, can’t find one that doesn’t make her look like a sex worker. I’m just so disappointed in how overly sexualized women are.

Merry was easy to tap into. I found a younger self in her and some of her fragility, and she’s a pugilist and a fighter. She’s Jake LaMotta. You can kick her so she’s no teeth left, and she’s gonna kick you back. She makes a lot of mistakes. She does some terrible things in the book. She’s no hero. but her sheer perseverance and her refusal to just be a victim interested me.

I understood Nina’s childhood better, even though her experience is so foreign to me. Perhaps because it was written in a more episodic way. How did you get to know the Bosnia she experiences? Those scenes are very powerful.

I was at a lecture that Sasha [Alexander] Hemon was giving in Paris. It was just when Trump was elected, it’s 2016 January, and he began, “You think that you live in a beautiful city. And it can’t happen to you. But I am here to tell you that it can happen, and it did, and it will, and it’s going to happen now.” That you think you live in a beautiful city just stuck with me, and then I started to write that chapter. I wanted people to understand that what happened in Bosnia, what happened to our families in Europe, what’s happening in Syria, it can happen anywhere. And will. If we don’t protect it.

When my son was working in Buffalo for AmeriCorps, he lived 3 miles from that supermarket where all those people were shot. I mean it’s ridiculous, but the way that we try to distance ourselves from the possibility of these terrible things. That was the goal of that chapter, which is to say, you better preserve what you have now, because this can happen to you. It happens every day all over the world.

One can do all the research in the world but still you have to get it onto the page, which is a challenge. The precision is remarkable. I’ll never forget the scene with Nina’s father, who is lost in the war and how we get farther and farther away from him — or he from us — and we don’t know his outcome. No one does. You write about Bosnia and you also write about Israel. As you noted earlier, American Jews have a complicated relationship with Israel. How did you feel writing those sections?

I was writing about civil war through this book, and Israel is in a perpetual state of civil war. And I feel for Israel and the Israelis, who, like me, think peace is better than endless war and want to treat Palestinians as their fellow citizens and equals. I’m horrified by everything else. You always do better when you support people. Instead of tearing down houses, they should be building hospitals and schools. But I have to live with those complexities just like I have to live with the complexities of being an American right now. I don’t know if Israel can survive what’s happening to it now, and I don’t know if we can survive what is happening to us. To not write about this is to not do my job.

I don’t know Birthright personally, but this section was hilarious to me. You’re both skewering and celebrating that experience. There’s a really interesting moment at the beginning of the scene when the students are told to go to one side of the room if you support a two-state solution, and then the other is … One state? Is that the other option? At the end of the experience, the single-state side of the room is far more populated.

My son went on Birthright, and I don’t want to speak for him, but he really loved the country, yet he also felt the whole machine of Birthright is propaganda. Israel is a powder keg, and so are we. We’re all locked and loaded, and everybody’s full of hate. Yes, there’s a lot of beautiful things happening in our country. But there’s a lot of hate.

And yet the book is not all solemn. There’s also humor to it. So, I want to talk a little bit about the tone. Even with Merry: I’m on her side but sometimes I’m laughing at her. She’s this privileged celebrity, who has little contact with reality. Again, are we skewering her? Are we celebrating Merry? How are you walking that line?

Merry is so deprived, and yet she’s been coddled, and then she’s been hurt, and she’s never had real love, and she’s a hot mess. I think the job of a novelist is to get at the moment in the culture. One of the things that has both complicated my life and helped me, maybe as a writer, but maybe not so much as a person, is that I can always see everybody’s side. I embrace the grayness of it in terms of complexity. I want her to be funny. It’s not a dirge. It’s not homework.

Merry continued to work for him. I wanted to show how that can happen; many women just want to push it aside. So that’s how you get these women who Harvey Weinstein raped and then worked with. They also fell under his Svengali spell, and they needed the job, and he destroyed anybody who got in his path. So, there were women who were attacked by him who ended up in his employ. Some of them actually had consensual sex with him after it but that doesn’t mean that he didn’t rape them, and it doesn’t mean that they’re bad victims, which is what the press does to them. You know there’s a good victim, and there’s a bad victim, and like if your skirt’s too short, or you did a nude scene, you’re a bad victim. Merry is a terrible victim, but she’s a victim.

The women are really drawn to each other. Nina in the end, you realize, has been affected very much by Merry, probably because she has steered her life and career decisions in many ways. What draws them to each other?

I think Merry falls in love with Nina. But Merry has the life that Nina dreams of. It’s so American because for Merry, the life is cruel and punishing, and almost unlivable. And yet to the child who grew up during civil war in Bosnia, it’s the dream.

I think what happened to Merry was horrible. But what happened to Merry is familiar.

What happened in Bosnia we know on a much smaller scale. But the crimes were very similar to the Holocaust. The Children’s War Museum in Sarajevo shows toys and letters but there is also a picture of infants, who were swaddled up and put on to bus seats with a seat belt unaccompanied by adults. A bus load full of them like the Kindertransport-parents, mothers who gave their children to drive out of Sarajevo to safety. And you see these really cute little babies just all alone on these seats, in one picture, and then in the next picture they’ve all been massacred because the snipers shot low from the hills to kill the babies, and so it’s a busload of dead babies.

It doesn’t really compare to the experience of Americans. And so, we get anger from all around the world. Even though terrible, terrible things happen in this country, and the country was built on slavery, which is the most terrible, and it’s the thing that undoes us, but when you think about living in Syria now, or Sudan, if you think about living through the siege of Sarajevo, if you think about living in the West Bank, it’s really different. Nina is very jealous of Merry.

Do you see a connection with your earlier work?

I think what I’ve been doing in my work, maybe not on purpose, is being a cultural historian and making these little time capsules of the way we live. So that’s really hard.

And how do you move on? What are you working on now?

It’s during the war, and it’s in southern France, and we just went on my spring break to do some research. We hiked the Walter Benjamin trail from France into Spain and found the hotel where he died. It’s a powerful experience. You walk through that trail that oh-so-many Jews used to escape from France. As you know, he was carrying his manuscripts, and he was so out of shape and so frail. It is a gorgeous fucking hike through vineyards, and stone terraces, and waterfalls. You’re in the Pyrenees. It’s incredible. The experience of Europe is in opposition to itself, because the food is great, the wine is great, it’s completely gorgeous, the people have great taste, there’s wonderful art, and yet they massacred all these innocent people and gave them to the Nazis and you have to live with both while you’re climbing this gorgeous trail that they were climbing to save their own lives.

You are the fiction chair of the creative writing program at the New School. How do you think American fiction has changed in the last decade or so? Our students have lived through so much these past few years.

We have students from all over the world, all over the country. They come from every economic stratum. They are every gender, and the New School is a safe place for them in a really unsafe world. When I started teaching I was 28. I was so young, and I could relate to everything the students were writing. They don’t read the things that I used to read so a lot of my references are new to them. But their references are also new to me, and they keep me at least more abreast, I think.

Once someone handed me a page of Saul Bellow’s manuscript from More Die of Heartbreak, and I’ve always given it out for a day of class to show how writers revise. And of course, since that time everybody works on a computer, but this is revised on a typewriter with a pen, cutting and pasting and moving it around; it shows how deeply people go into it. But in the last 10 years only one student has ever heard of Saul Bellow. So, he’s gone. Contemporaries of mine that I thought were going to go down in history? Their books have lost their following. Nobody has heard of any of them. Writing and publishing? The whole world has changed.