Beloved and loathed, decisive or stubborn, icon or enemy of feminism — does Golda Meir deserve any of her reputations?

Deborah Lipstadt’s new biography aims for a fuller portrait of the prime minister

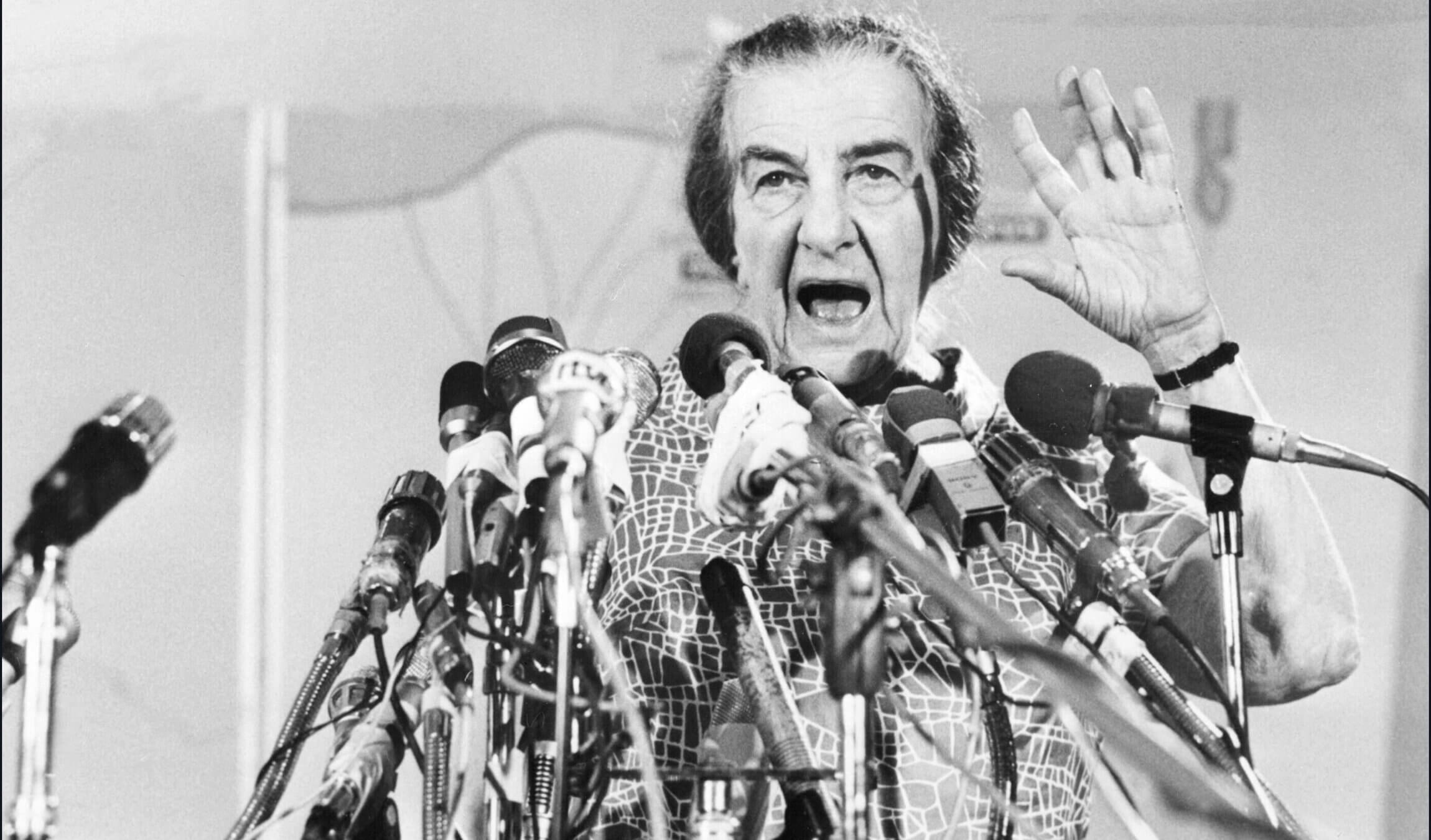

Golda Meir at a 1973 radio address after the Yom Kippur War. Photo by Gabriel Duval/AFP via Getty Images

Golda Meir: Israel’s Matriarch

By Deborah E. Lipstadt

Yale University Press, 288 pages, $26

The pivotal event in Golda Meir’s decades of public service takes up fewer than 10 pages of Deborah E. Lipstadt’s new biography — but, for all the good it did Meir’s political capital, it’s fitting that it’s all in Chapter 11. The 1973 Yom Kippur War was the moment Israel lost its confidence in her leadership, all but forcing a government reorganization that ended in her resignation a few months later. For better, but more often worse, it is the moment that defines her time in office.

While a new Helen Mirren-led biopic tells the story of Israel’s only woman prime minister during the costly conflict she deemed perhaps her greatest failure, Lipstadt’s book, Golda Meir: Israel’s Matriarch, is a holistic portrait. It neither neglects nor erases Meir’s shortcomings, but finds in them the same worldview that fostered her many successes.

Lipstadt, a historian and President Biden’s special envoy to monitor and combat antisemitism, has set out to write a profile that resists the hagiography or hatchet job of previous attempts to chronicle Meir’s life while coming in at under 300 pages. (Francine Klagsbrun’s hefty Lioness (2017), cited by Lipstadt, was received by some as a work of reevaluation and even rehabilitation and Pnina Lahav’s The Only Woman in the Room (2022) mainly reckoned with Meir’s legacy through a feminist lens.) As Lipstadt writes, Meir’s “long career encapsulates a microhistory of the Jewish state.” And so we are introduced not just to Golda Mabovitch, who never outgrew the fear of Cossacks outside her window or mastered the art of biting her tongue, but to a thumbnail history of Israel’s founding and the origins of problems that persist today.

Born in Kyiv in 1898, Golda saw her father board the doors of their house against pogroms, a formative memory that would convince her “Zionism represented an antidote to a hostile, Jew-hating world.” At 8, she moved to Milwaukee, prompted in part by czarist surveillance of her sister’s Labor Zionist meetings. She took to English quickly — she never would completely master Hebrew — and soon proved her skill as an orator, advocating for poor students in need of textbooks.

Her early reception in the U.S. (she was featured in the local paper for her textbook advocacy) anticipated the adoration that continues today in her second home. But Golda, whose Labor Zionist convictions drove her to make aliyah in 1921, is a more controversial figure in Israel. Clinging to the ideal of the Jewish state, she often missed the practical problems in front of her.

In the beginning of her life in the Yishuv, Golda proved invaluable to the pre-state community as a spokeswoman extraordinaire, whipping up enthusiasm and funds from working American women and eventually courting wealthy men to donate millions to the cause of the Jews of Palestine’s defense. It’s doubtful her sales pitch would have played quite so well had she not been convinced the nascent state was an investment, not a charity.

The investment paid off, and when Israel became a reality, Golda, now going by Meir, a hebraization of her married name, Meyerson, was a tough, arguably unyielding, negotiator on its behalf.

Remembering how little other countries did to save her coreligionists, her default as foreign minister was to speak plainly with a diplomatic style one journalist said had “all the subtlety of a Centurion tank.” She was convinced to the point of intransigence that Jews could only rely on themselves — a lesson learned in her dealings with the British in Mandatory Palestine and from her presence as an observer at the Evian Conference, where the delegates from over 30 nations decided it was too much trouble to take in Jewish refugees.

But domestically Meir’s way of playing politics, which, Lipstadt is right to note, has all too often been viewed through the filter of her gender, motherhood and later her age, often alienated those she’d meant to help and did even deeper damage to those she was indifferent to.

While she was the country’s most powerful woman, she often dismissed feminists as being in a “war against the male gender.”

Even as she advocated, as a successful secretary of labor and employment, for unrestricted immigration, she revealed a prejudice against newly-arrived Mizrahi Jews, suggesting they didn’t know how to work. Decades later as prime minister, when the Israeli Black Panthers, many of them children of that initial wave of Mizrahi immigrants, demanded her attention in light of their poor living conditions, she callously told them to “start working” to improve their situation.

Golda and the Ashkenazi leadership in her orbit “could not comprehend that this might be a problem rooted in ethnic discrimination,” Lipstadt writes. Meir so believed in Israel’s uniqueness as a haven for Jews, and the socialism that animated her particular brand of Zionism and the social programs she spearheaded, that she couldn’t detect the reality of its prejudice.

Concerning the Palestinians, Meir said in an infamous interview that “there is no such thing as Palestinians,” a remark she attempted to clarify by noting her own classification as “Palestinian” on her British-era passport.

“[S]he seemed unable to feel their deep sense of humiliation and deprivation,” Lipstadt writes of Meir’s attitude toward Palestinians. “Some of her critics consider her inability to see nuances among the Arabs as her Achilles heel, causing her to miss crucial opportunities to reach out to Israel’s neighbors.”

And yet, while she refused to withdraw from territories gained in the Six Day War as a prerequisite for peace talks, Meir was opposed, for demographic reasons, to keeping them in their entirety, and “disdained what she considered the fanaticism of those Israelis who supported keeping the territories on theological and historical grounds.”

We may not need to do much guessing at what she’d think of the settler movement today. And yet, we are still learning more about Meir. Recently declassified minutes from 1970 now show that she was open to the idea of a Palestinian state.

“I am ready to listen as to whether there is a glimmer of hope for an independent Arab statelet in Samaria and Judea, and maybe Gaza too,” Meir said, adding with her trademark candor, “If they call it Palestine, so be it. What do I care?”

The meeting was held on Erev Yom Kippur, and while it adds a shade of nuance to the woman we think we know, it will likely never be the Yom Kippur we remember her for.