How a few judiciously placed slices of New York Jewish cheesecake changed the world of rock ‘n’ roll

Richard Gottehrer’s trip to pop music immortality began with good timing and good dessert

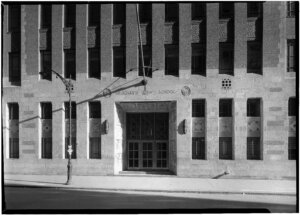

For Brill Building regulars, Jack Dempsey’s restaurant was the most convenient spot for cheesecake. Photo by Getty Images

Never underestimate the power of New York cheesecake.

There are many reasons that Richard Gottehrer has enjoyed six decades of success in the music business — a sharp ear for a good hook, a sharp eye for changing musical and technological trends, a natural ability to click with up-and-coming artists, and a lifelong passion for music itself. But knowing how and when to leverage one of the Big Apple’s tastiest delicacies hasn’t exactly hurt, either.

Back in the 1960s, when the songwriting and production team of Gottehrer, Bob Feldman and Jerry Goldstein (a.k.a. FGG Productions) was cutting hits for the likes of The Angels, The McCoys and their own band The Strangeloves, the best way to tell if a recording was a potential smash was to hear how it sounded over the AM airwaves — but few radio stations were willing to spin pre-release acetates, unless of course there was bribery involved.

“In order to hear if the song’s mastering was right, you wanted to hear it on the radio,” recalls Gottehrer while seated comfortably in the casual confines of a conference room at the Greenwich Village headquarters of Orchard Music, the Sony-owned music distribution company he co-founded in 1997 and where he currently serves as Chief Creative Officer.

“We had some DJ friends at WKBW, a 50,000-watt station in Buffalo, New York,” he said. “So when we’d finish mastering a single, we’d get a New York Jewish cheesecake from Jack Dempsey’s Restaurant in the Brill Building, we’d package it in dry ice, and we’d put the acetate of the single on top of the cheesecake and send it to WKBW. They couldn’t get cheesecakes like that in Buffalo.

“When they got it, they’d call and tell us when they were going to play the record. There was a place out by LaGuardia Airport in Queens where you could go and pick up the station’s signal, so we’d drive out there at the appointed time and get the 50,000-watt playback through the car radio — and that way, we could decide if the record needed remastering or not.”

In the late 1960s, after Gottehrer had amicably split with FGG to co-found Sire Records with Seymour Stein, the cheesecake connection once again came in handy.

“There was a shift in the music business,” he said. “All the hits were still at AM radio, but records were starting to be made in stereo, and FM radio was on the rise because the kids could now experience music with a wider spread. So we started traveling to Europe and the UK, and licensing finished recordings by new bands that were perfect for FM radio, but the American companies didn’t want to release them because they were not hits in the UK.

“So when we would go to the UK labels, we’d go straight to their export divisions. And at first, you know, you’re nice, you bring a gift, and we would bring the cheesecakes — I think we were getting them from the Turf Cheescake Company on the Upper East Side by this point. Next time we’d go back, they’d say, ‘You got the cheesecakes?’ And I’d say, ‘Of course! What do you got for us?’

“And that’s how Sire began to grow,” he said.

‘I kept writing songs’

Born in the Bronx in 1940 to Jewish parents of Austrian and Russian-Polish heritage, Gottehrer first fell in love with the big band sounds of Benny Goodman before he became obsessed with the blues and boogie-woogie. He got an early education in the congenial hustle and unconventional workings of the record business at the age of 14, when a passerby happened to hear him banging away on his family’s piano through an open living room window.

“It turned out that the guy was a songwriter that had a small publishing company in 1650 Broadway, which is part of that area that we call ‘the Brill Building,’” Gottehrer said. “So I went down and I got a little taste of the business; someone he brought me to made a few demo records with me. I knew nothing about making records at the time, and nothing came of the demos. But it got a bug going with me, and I kept writing songs.”

By the early 60s, Gottehrer was on track to become a lawyer, enrolling at Brooklyn Law School after graduating from Adelphi University with a B.A. in history. But he couldn’t shake the songwriting bug, and he began stopping off in Midtown Manhattan on his way from the Bronx to Brooklyn in order to pitch his songs to various Brill Building publishers.

“You’d knock on doors and if they liked your song, they would take an option on it and give you a $25 advance, and they would try to place it with an artist. Artists were not writing their own songs in those days; they were looking to these particular publishers.”

By 1963, Gottehrer was doing well enough with his song pitches that he stopped going to school all together.

“What you had at that time was a business where they knew things were changing,” he said. “The majors didn’t really care that much, but the smaller publishers and the independent record companies, were interested in kids my age and a bit younger — basically, white kids that could interpret this, quote, new environment; you’d write sort of popular songs, but they’d have R&B beats and other things going on. I met two other guys, Bob Feldman and Jerry Goldstein, who were shopping their wares to the same publishers, and we became a writing team.”

The trio signed an exclusive deal with Roosevelt Music, where they formed a winning alliance with Wes Farrell, an experienced songwriter and promotions man.

“He would make the contacts, we’d go and play ‘em our songs, and we’d make demos of the songs they liked. And by making demos, we learned how to produce records,” said Gottehrer.

They didn’t come from the land down under

The FGG songwriting and production team first struck serious gold with The Angels’ girl-group classic “My Boyfriend’s Back,” which, 60 years ago, topped the Billboard Hot 100. Several other singles followed, but without much success — times were again changing, as indicated by the title of The Angels’ 1964 song “Little Beatle Boy.”

“The whole Brill Building thing began to fall apart as the Brits were coming in, writing songs themselves,” Gottehrer said. “Bands like the Stones, the Beatles, they at first did songs from our era, but they started writing their own. So we put out our own record as The Strangeloves, and on the record, Bob Feldman did a narration with a fake British accent.”

Though that Strangeloves single — 1964’s “Love, Love (That’s All I Want From You)” — wasn’t a big hit, it somehow blew up in Virginia Beach, Virginia. “A DJ there invited us down to play a show, but he said, ‘You know, because of the accent, everybody thinks you’re from England.’ I said, ‘Well, we can’t be from England; nobody would believe it.’ So we became Australian, because most kids in America in 1965 had never met an Australian.”

And so it came to pass that three Jewish guys from New York reinvented themselves as Giles, Miles and Niles Strange, three Australian brothers who’d left their family’s sheep farmers to find fame and fortune playing rock n’ roll. The endearing absurdity of the ruse was further compounded by the band’s visual accoutrements, which included spears, African drums and zebra-skin vests.

“We had all these things that had nothing to do with Australia,” Gottehrer said with a chuckle. “But they had a foreign element to it, and that was enough.”

Top of the pops

Ultimately, The Strangeloves succeeded not because of their goofy gimmick, but because they made some truly indelible rock n’ roll records. “I Want Candy” rode a stomping Bo Diddley beat to #11 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the summer of 1965, and its pounding follow-ups “Cara-Lin” and “Night Time” both made it into the Top 40.

All three songs would be covered repeatedly over the ensuing decades by artists including Bow Wow Wow, the Fleshtones and the J. Geils Band. (The bandwagon-jumping “Australians” also did quite well in the UK, where the FGG-penned song “Sorrow” was recorded by The Merseys and David Bowie, and received a shout-out by George Harrison on The Beatles’ “It’s All Too Much”.)

The Strangeloves were signed to Bang Records, an independent label run by New York songwriter and producer Bert Berns, whose many accomplishments included co-writing the Vibrations’ 1964 R&B hit “My Girl Sloopy” with Wes Farrell. Retitled “Hang On Sloopy,” the song had become part of the Strangeloves’ live set, with Gottehrer, Feldman and Goldstein viewing it as an eventual follow-up to “I Want Candy,” which was then just starting to climb the charts. But when tourmates the Dave Clark Five expressed interest in cutting the song themselves, the FGG team sprang into action and recorded “Sloopy” with the help of a young Ohio band called The McCoys, which featured a 17 year-old Rick Derringer on lead guitar and vocals.

“We had already made the track to ‘Hang On Sloopy,’” says Gottehrer. “We signed the band to a production arrangement and had them sing and play a guitar solo over the track we had. And it became a hit record.”

Released on Bang, the FGG-produced “Hang On Sloopy” wasn’t just a hit record — it went all the way #1 in October 1965, paving the way for several other successful collaborations between FGG and the McCoys. The song also brought Gottehrer and Seymour Stein together for the first time.

“Seymour was doing independent promotion, and Bang hired him to promote ‘Hang On Sloopy,’” Gottehrer said. “So we met during the course of that, and decided to become partners and go into business together. It’s not that I left Bob and Jerry, but we’d reached a point where Jerry wanted to go to California, and it wasn’t really working the same. So I wanted to move on. But the great thing is, we all stayed friends.”

Though Gottehrer and Stein’s new Sire Records began as a production company — the legendary 1967 single “Garden of My Mind” by British psych-rockers The Mickey Finn was one of Gottehrer’s first productions for the concern — it soon shifted to cheesecake-assisted record distribution. Within a few years, Gottehrer and Stein bought an interest in the British label Blue Horizon, the original home of British blues bands Fleetwood Mac and Chicken Shack, and successfully introduced Dutch prog band Focus — whose yodeling rondo “Hocus Pocus” became a surprise US Top 10 hit in 1973 — to these shores.

‘A whole different approach’

Sire would go on to play a significant role in the punk and new wave movements, signing bands like the Ramones, Talking Heads, The Dead Boys, The Undertones and Richard Hell and the Voidoids, and would become a commercial powerhouse in the eighties thanks to acts like Pretenders, Depeche Mode and Madonna — but Gottehrer was already long gone by then.

“We signed the Ramones to Sire while I was still there, but I sold Seymour my shares at Sire, because it had become a sort of uncomfortable environment — we’d both gotten married, and our wives didn’t get along,” he said with a shrug. “So I left, and started hanging around down at CBGB, and got involved with some of the artists out of the punk scene. It was rooted back in sixties music, but it was real — it wasn’t manufactured or contrived.”

Gottehrer produced Blondie’s first two albums — 1976’s Blondie and 1977’s Plastic Letters — as well as Richard Hell’s 1977 debut LP Blank Generation and several records each by NYC rockabilly revivalist Robert Gordon and British roots rockers Dr. Feelgood. These projects led to him producing hit albums by Joan Armatrading (1980’s Me Myself I) and The Go-Go’s (1981’s Beauty and the Beat and 1982’s Vacation), as well as Marshall Crenshaw’s landmark, self-titled 1982 debut. Gottehrer has stayed active as a producer to the present day, with several albums by Dion, Dum Dum Girls and The Raveonettes on his 21st century resumé.

“I’m probably better suited for working with an up-and-coming artist than someone who’s already successful,” he says, when asked about the many stellar debut albums he’s produced over the years. “I don’t know why, but I guess part of it’s a challenge — the idea of taking something from the bottom and seeing the value of it, recognizing it and allowing them to be able to really express it. So it’s a whole different approach.

“And sometimes producing records is very difficult, because you don’t find success all the time. It doesn’t mean it’s not great; it just means you don’t find the success. In this business, when things start drying up and you’re not successful, people may like you, but they’re unwilling to pay you for the privilege anymore,” he laughs. “People move on to different producers, and I understand that. If I were giving a talk and trying to inspire somebody, I would tell them, ‘It’s not the heights that lead you to greater heights. It’s when you are in the middle and the bottom falls out, how do you pick yourself up and get back up even further?’”

‘The music still excites me’

In 1997, the wheel once again landed on Gottehrer’s number. Sensing an opportunity in the then-nascent world of internet music distribution, Gottehrer and Scott Cohen co-founded The Orchard, which began as a distributor of independently-released CDs but soon branched out into digital music sales.

The Orchard, which now has offices in over 45 cities worldwide, continues to grow in a variety of directions. In 2021, the company signed a global distribution partnership deal with the Latin American label Rimas Entertainment, an arrangement which resulted in a #1 album this spring — Un Verano Sin Ti by Puerto Rican rapper Bad Bunny. And this summer, The Orchard formed a partnership with Just Call Me By My Name, a new label formed by the non-profit Daniel’s Music Foundation to release music by artists with disabilities.

“The music still excites me,” says Gottehrer, “but what excites me more than that is the change in the environment of things — you know, how the music business changes, and how society changes because of technology and the changing world around them. I like that Bad Bunny was #1, not just because we have him, but because he’s a symbol of how we respond to a changing world, where a different culture can influence us. It represents not just the Spanish-speaking population, because his music clearly gets a response from many people who don’t even know what he’s saying.”

When Sony, which acquired a majority stake in the company in 2012, paid over $200 million in 2015 for the remaining equity in The Orchard, Gottehrer could have easily taken his cut and retired. Instead, he continues to run the recording studio in the company’s New York office, produce Orchard artists, and serve as, in his words, “an ambassador for the company.” Most of his friends and colleagues from the Brill Building days are retired or gone — Seymour Stein and Bob Feldman both died this year — but at 83 years of age, Gottehrer is still having too good a time to think about slowing down.

“It’s simply what I do,” he said, eyes twinkling with obvious delight. “What everybody else does for entertainment at a holiday, I do every day. I eat where I want. I travel around the world to all the places that we are involved with. I just never thought that there would be a time that I wouldn’t do it; I don’t get that sort of thinking. I know people try to accumulate whatever it is they need to accumulate to retire and then enjoy life, but I basically enjoy life anyway. What am I gonna do? Work in the garden?”