How a sly Jewish playwright wrote ‘the Citizen Kane of horror movies’

Despite unassuming beginnings, Anthony Shaffer’s ‘Wicker Man’ has become a cult film of gargantuan proportions

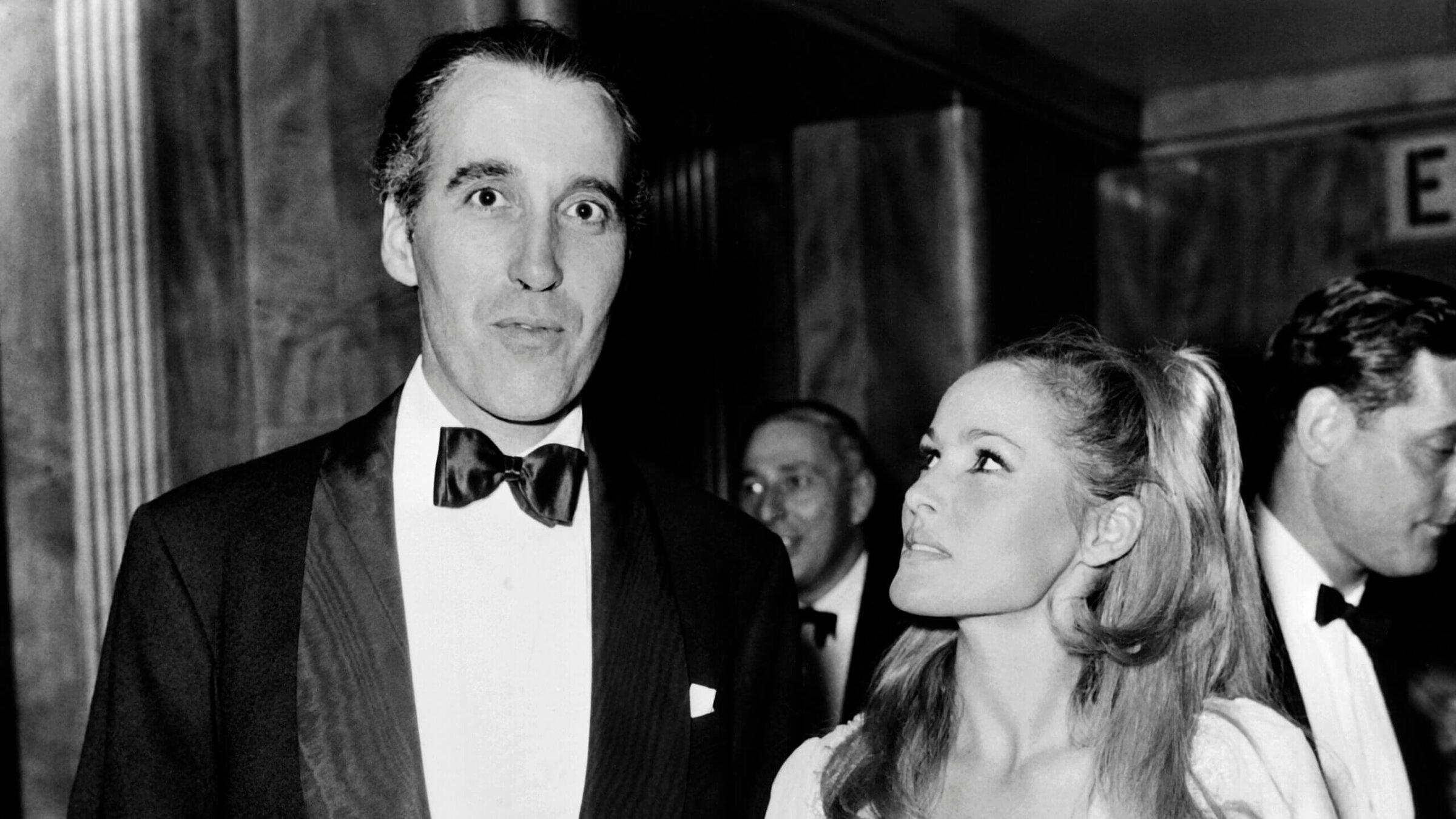

‘Wicker Man’ star Christopher Lee with Ursula Andress. Photo by Getty Images

Fifty years ago this week, the film The Wicker Man was test-screened to the public for the first time. Shot in haste on a small budget, its production badly beset by weather and studio politics, and ham-fistedly edited for release at the behest of British Lion executives whose reactions to the film ranged from sheer confusion to outright loathing, the horror film would be officially released to UK theaters in early 1974 with a prohibitive “X” rating, as the undercard of a double feature with Nicolas Roeg’s more acclaimed Don’t Look Now. After several hiccups with American distribution, the film would finally appear stateside that August as an R-rated drive-in feature with little to nothing in the way of promotion or press coverage.

And yet, despite such unpromising beginnings, and despite the fact that a fully restored version of the film has yet to surface, over the subsequent five decades, The Wicker Man has gradually assumed a rather gargantuan cult stature. Now considered a massively influential cornerstone of the folk horror subgenre, the film went on to win the Golden Licorn for Best Film at the 1974 Paris International Festival of Fantastic and Science-Fiction Film awards, and Best Horror Film at the 1978 Saturn Awards in the US. The Wicker Man regularly appears on “greatest horror films of all time” lists, and the continuing interest in the film has spawned both a sequel (2011’s The Wicker Tree) and a predictably awful 2006 remake starring Nicolas Cage.

The film’s extensive influence has also impacted the music world — via both Paul Giovanni’s haunting original soundtrack and the various narrative elements that have inspired songs and videos by everyone from Iron Maiden to Radiohead —and the annual Burning Man is just one of several festivals to emerge in the film’s wake to feature neo-pagan themes and the torching of a giant effigy.

British actor Edward Woodward, who plays the film’s protagonist — a devoutly Christian police officer investigating the disappearance of a young girl on a remote Scottish island where a form of Celtic paganism has supplanted Christianity — considered it one of his finest performances. Horror legend Christopher Lee, who plays the laird whose family restored the worship of “old gods” to the island a hundred years earlier, considered the film the best of the hundreds he’d acted in. Lee went to his grave in 2015 still hoping that the original edit of The Wicker Man would one day resurface.

The tart exchanges between Woodward’s Sergeant Howie — a puritanical, self-righteous, by-the-book copper who’s absolutely appalled by the islanders’ sex-positive, nature-worshipping ways — and Lee’s rakishly charming Lord Summerisle provide some of The Wicker Man’s more humorous moments, making the story seem at first like something of a dark fish-out-of-water comedy.

“And what of the true God?” a frustrated Howie demands, “Whose glory, churches and monasteries have been built on these islands for generations past? Now sir, what of him?” “He’s dead,” Lord Summerisle smirks. “Can’t complain, had his chance, and — in modern parlance — blew it.”

Though many viewers and critics through the years have understood The Wicker Man as a showdown between Christianity and paganism, with the former (as represented by Sergeant Howie) receiving a well-deserved if deeply disturbing comeuppance at the film’s conclusion, Anthony Shaffer — the Jewish playwright and screenwriter who wrote the screenplay — always maintained that he wasn’t taking a particular side.

“I didn’t write The Wicker Man as an atheistic picture,” Shaffer explained in a 1977 interview with Cinefantastique. “If you look at it in one way, it’s Christianity that is the new boy — it’s only been going for 2,000 years. The [pagan] stuff in our film has been going on for thousands and thousands of years.”

Along with his twin brother, the even more famous playwright Sir Peter Shaffer (Equus, Amadeus), Anthony Shaffer was born to a middle-class Jewish family in Liverpool, England in 1926. Shaffer’s own degree of observance is unclear — several sources claim that his parents were Orthodox, but Shaffer’s longtime business partner and collaborator (and director of The Wicker Man) Robin Hardy remembered him in 2007 as “very much a Reformed Jew.” In any case, Shaffer saw The Wicker Man not as a religious statement, but rather as an opportunity to explore the horror potential of Celtic mythology.

“I don’t think a serious film on the subject had been done before,” Shaffer, who died in 2001, told author Stephen Appelbaum. “The subject opened the world of horror and terror, but also had an intellectual content which gave us a chance to do something quite provocative.

Then came the question that unlocked things, or the McGuffin, as Hitchcock would say: What makes the perfect sacrifice? How do you choose that sacrifice that’s going to placate the gods, make the crops grow, or whatever the sacrifice is for?”

The inspiration for the screenplay came from David Pinner’s 1967 horror novel Ritual, in which a puritanical Christian police officer investigates the ritualistic murder of a child in rural Cornwall. Christopher Lee, a friend of Shaffer’s, was looking for a project that would be a little more highbrow than the Dracula series he’d starred in for Hammer Films, and he, Shaffer and Peter Snell — then the managing director of British Lion Films — bought the rights to Pinner’s novel. Shaffer, who had recently won a Tony for his play Sleuth, ultimately found Pinner’s source material unworkable, but was convinced by Lee and Snell to build a new story from the germ of Pinner’s original idea.

“The importance of Sleuth as an antecedent to The Wicker Man is hard to exaggerate,” Hardy wrote in 2007. “Sleuth is the quintessential games-player’s play… the pawns in the games of which I speak are human.” While Hardy insisted to Cinefantastique in 1977 that, “As to the pagan culture, everything you see in the film is absolutely authentic,” the islanders’ “heathen ways” in the film were not based one specific variety of paganism; rather, Hardy and Shaffer actually cherry-picked them from a number of sources, including Julius Caesar’s accounts of his Gallic Wars and Sir James G. Frazer’s The Golden Bough, weaving them throughout the screenplay as increasingly intensifying clues that “normal, everyday” life on the island is anything but.

“Terror comes from that feeling of everydayness,” Shaffer explained to Cinefantastique. “It’s like the scene in a sweet shop when they’re talking about everyday matters, and suddenly [the shopkeeper] does that thing where she puts a frog in the little girl’s mouth, to take away the ‘frog’ in her throat. It’s real! And then she gives the girl a sweet to get rid of the nasty taste, like any mother would. You see, you go between the worlds. And because it’s so normal, we can feel the terror beating very heavily.”

The music of The Wicker Man takes a similarly broad approach, mixing traditional songs, instruments and imagery with modern folk and psychedelia. Though the film’s soundtrack was composed, arranged and recorded by American musician and playwright Paul Giovanni, it was Shaffer who engaged Giovanni’s services and directed him to use the song collections of English folklorist Cecil Sharp as a musical template.

“My brother Peter had a boyfriend called Paul Giovanni, who was a damned good musician, though I didn’t know this at the time,” Shaffer recalled. “Peter said, ‘Why don’t you give Paul a crack at this?’ I didn’t like the idea at first, because it was like saying, ‘Use my cousin.’ But I talked to Paul and was impressed by his enthusiasm and knowledge. He took the challenge and rose to the occasion.”

As with the pagan customs of the townsfolk, Giovanni’s pastoral Wicker Man soundtrack — which has since exerted a profound influence on 21st century indie-folk and electronica — still seems both familiar and deeply unsettling. The music works beautifully in conjunction with Shaffer’s screenplay to impart the same sense of misdirection (and the building sense of terror) to the viewer that Sergeant Howie experiences in his dealings with Lord Summerisle and the villagers.

The police officer picks up on some of the clues that Shaffer’s script has dropped for him, but he doesn’t decode them quickly enough; he only realizes that he’s been a pawn in Lord Summerisle’s game during the film’s shocking final moments, when it becomes clear that (spoiler alert!) he’s about to be burned alive in a giant wicker effigy in order to ensure a bountiful spring harvest.

For Shaffer, Howie’s fiery ritual sacrifice represented not the triumph of the old gods over a newer one, but rather the perils of blind faith. “If we’ve learned anything at all, we realize that what affects us is precisely what we ourselves are prepared to do and not what a third force will do for us,” he told Cinefantastique. Howie’s blind faith leads him to die a martyr’s death, just as the blind faith of the islanders requires him to do.

Lord Summerisle, fully aware that his ancestors reintroduced paganism to the island in order to mollify and manipulate its populace, may be the only character in the film who doesn’t blindly believe in one religious tradition or another.

And yet, Summerisle’s pragmatism dictates that he must “play to the crowd” by having Howie ritually killed. We see a flicker of unease cross the laird’s features when Howie insists that his own death will do nothing to right the island’s failing crops; if they fail the next year, he says, it will be Summerisle who takes the fall. But it’s too late — maybe a century too late — for Summerisle to turn back now. “They will not fail!” he bellows, clearly trying to convince himself of what his villagers already believe.

“We don’t know if Summerisle’s sacrifice fails,” Shaffer explained to Cinefantastique. “The apples could come tumbling out of the trees that year, but if they don’t, the people will have to have another go next year. And they must go back to the community for the victim, and who’s the top banana there? The Summerisle character.

“You have to be left with a certain doubt,” he continued. “This time we leave the people in a very happy state; they’ve burned this man and they go home as if they’ve been to a football match… Now that’s real horror. However, for them, it’s not horrible because they believe in it.”

The unsettling ambiguities of The Wicker Man are not limited to Shaffer’s script or Giovanni’s music. Hardy’s direction places broad moments of comedy uncomfortably alongside hallucinatory tableaux; the film contains both genuinely erotic moments and nudge-nudge sex humor (both involving Britt Ekland, whose paramour Rod Stewart supposedly offered to buy up all the prints of The Wicker Man and have them destroyed); and there are several eccentric casting choices, including that of gorgeous Hammer vampire Ingrid Pitt as the town’s prim librarian, and the flamboyantly gay dancer and mime Lindsay Kemp, who can’t help but camp it up as Ekland’s innkeeper father.

But for many viewers, this unusual mixture of moods and characters is part of what makes The Wicker Man so compelling. The execs at British Lion didn’t think so, though — and then there was the issue of the film’s ending, where all of its amusing, mysterious and distorted elements give way to sheer terror.

“They were shocked by The Wicker Man,” recalled Shaffer. “When the lights went up at a screening we’d arranged for them, it was as if stalactites were descending from the ceiling. It was cold as a witch’s tit. Utter shock. They couldn’t believe that the hero was allowed to die in the end. Where was the cavalry? They had no idea how to sell the film and it was buried.”

Shaffer got the last laugh, however. Not only did he leave the project with a new love on his arm — Australian actress Diane Cilento, who played the island’s schoolmarm (and whom he would marry in 1985) — but he lived to see The Wicker Man become one of the great cult films of his time.

“The fact that it survived at all, let alone ultimately became something of a cult triumph, is a credit to the picture, the strength of the story, I think,” he reflected in a 1994 interview with Movie Collector magazine. “And the acting. I think a lot of the actors playing the locals are so good. You get a real sense of proper support playing. You often don’t get that in so-called horror movies, and I think they all played extremely well.

“Anyway, it survives in one form or another and eventually won the garland from an American movie magazine [Cinefantastique] ‘the Citizen Kane of horror movies,’ which is something that one treasures.”