How using words like ‘redemption’ and ‘civilian’ shapes the thinking on Israel’s war with Hamas

Given the gravity of current events, it’s easy to ignore the nuances of language — but they’re crucial

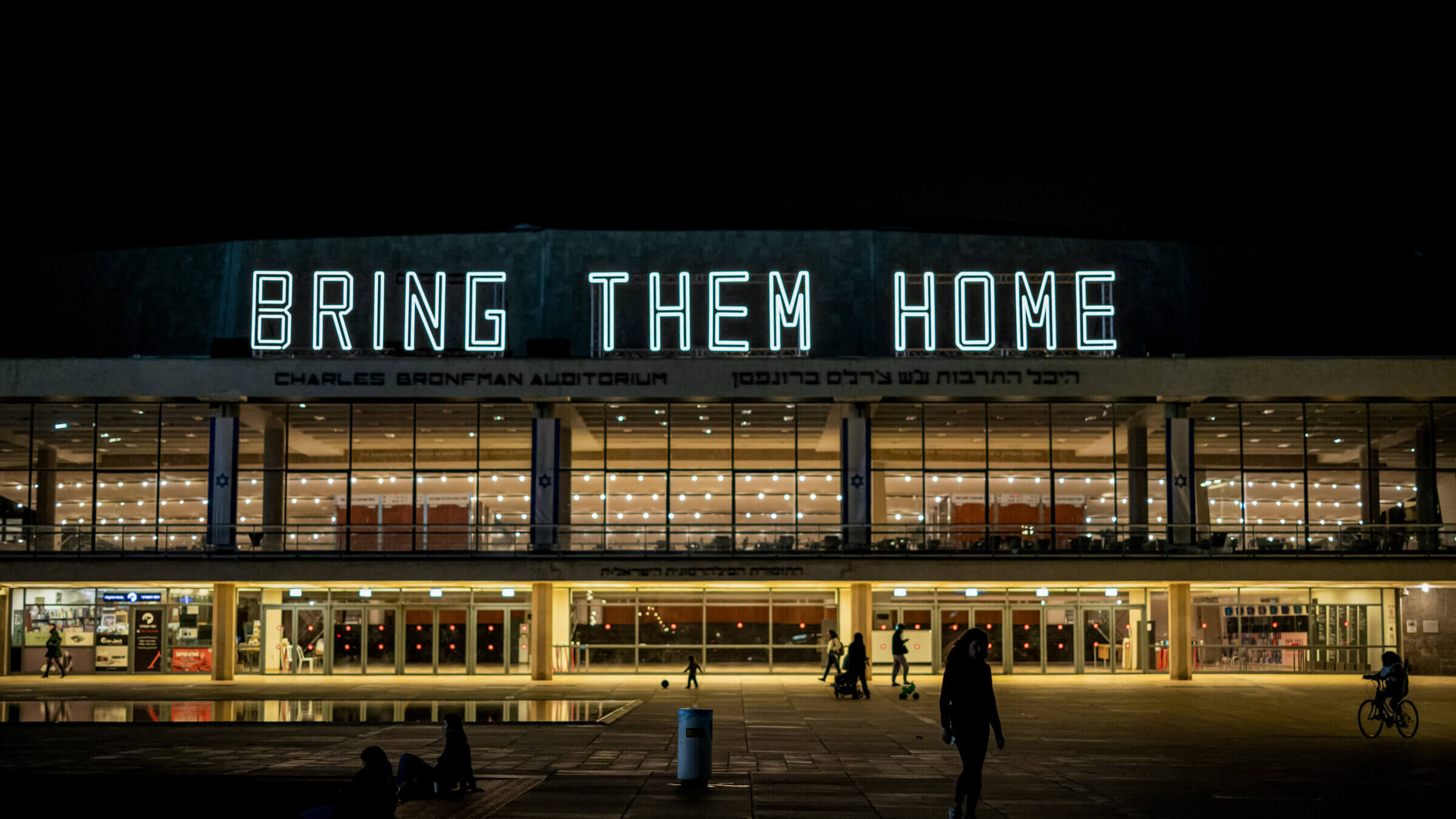

A view of the Charles Bronfman Auditorium in Tel Aviv. Photo by Getty Images

A former foreign correspondent in Israel sent along an intriguing email with the subject line: “Redemption of Hostages.” The email was from the Government Press Office in Israel, and she wanted my take on it.

At a time when 129 hostages are still held by Hamas and other terrorists, it may be hard to focus on language, but that was what the journalist wanted to discuss. She pointed out that her Hebrew-speaking husband didn’t think the phrase came from Hebrew.

“Redemption of hostages” is an interesting word choice, because it departs from the Hebrew l’shachrer et ha’chatufim, or, literally, to release those who were grabbed or stolen, which is what Israeli news media is calling the effort to get the hostages out.

“Redemption” is instead a nod to religious language — and the mitzvah of pidyon shvuyim or redeeming captives.

In fact, in his translation of the Talmud into English, Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz renders pidyon shvuyim as “redemption of captives.”

“The Gemara asks: What is the reference to animals of the righteous, about whom it is stated that God does not generate mishaps through them? It is based on the incident when Rabbi Pinchas ben Ya’ir was going to engage in the redemption of the captives, and he encountered the Ginai River.”

An old problem rears its head again

That phrase “going to engage” — a translation of the Aramaic hava k’azil — or literally, as he was walking, reflects the regularity of the captivity problem in Jewish history, which is one of the many reasons Jews feel like we are living through terrifying historical flashbacks.

For centuries, Jews were grabbed and then imprisoned. The only possible way out was money, usually lots of it. And the state of Israel has a long history of doing everything possible to release soldiers who have been kidnapped — such as the 1027-for-1 deal for Gilad Shalit — though the current situation, with civilians, including women and children, all held for months by Hamas, is unprecedented.

“Redemption” makes the release of hostages into a religious obligation, not just a national-security quandary.

But wait a minute. Consider the other side of the equation: Does that mean Hamas is now being cast in the role of “redeemers”?

It’s fair to assume that the Israel Government Press Office is not trying to praise Hamas with its language, but many news outlets are seeming to intentionally or unintentionally praise Hamas with their choice of words, every time a hostage leaves captivity.

Consider this headline from Reuters: “Hamas frees eight hostages to Israel as talks seek to extend Gaza truce.”

The use of the word “frees” makes Hamas sound magnanimous, acting out of the goodness of its heart. It unfortunately has the echo of “freedom fighters” too.

By contrast, Israel’s i24 News went with the word “released”: “President Herzog calls for release of Hamas hostages in New Year’s message.”

What hostages are saying about their experience

The language issue extends to what former hostages are saying about their time in captivity.

21-year-old Mia Schem, whose family chose not to speak with The New York Times, did give two extensive and harrowing interviews to Israeli television. I watched both, spellbound; one has been translated into English and can be seen on YouTube. (I hope the other one will get English subtitles, soon, as it should be required viewing )

Schem described being held in the home of civilians in a small room — just 2.5 meters by 2.5 meters — with her male captor staring at her all day and all night. She was not allowed to shower for 55 days.

When she was initially taken captive, she was shot in the arm; and after several days, she was taken to a hospital where a veterinarian operated on her without anesthesia. The vet told her she would not make it out of Gaza alive. She was then sent back to the home of an ordinary family in Gaza.

Schem describes the man’s wife and children — how the wife would bring coffee for her husband but not Mia, how there were days she did not give Mia any food at all.

“She did not like that I was in the same room with her husband, so she would taunt me. She would bring him a meal — and for me, nothing,” Schem tells the interviewer.

“It was like I was an animal,” she said.

They are all Hamas over there, just one big family, she said. Her testimony makes one wonder just what we mean when we use the word “civilians.”

What does ‘civilian’ mean?

Schem is not the only hostage who has specifically reported being held by civilians, not Hamas fighters. In an incident that deserves far more coverage, one hostage, 25-year-old Roni Kriboy, managed to escape but was nabbed and returned to captivity by “civilians.”

In The New York Times, Ruti Munder, a 78-year-old Israeli grandmother, related her experience with both “hospitals” and “civilians.”

“Over the next 49 days, I spent most of my time locked in a small room on the second floor of a hospital. My jailer, who went by Mohammad, called himself a soldier of Hamas, but he didn’t look like a soldier. I was being guarded by a man in civilian clothes and held against my will in a civilian building,” Munder reported.

The role of ‘women and children’ in holding hostages

The saddest part of Mia Schem’s interview is that it forces viewers to reckon with the constant news coverage on the deaths of “women and children.”

That’s not a phrase that usually requires explanation. The connotation is that “women and children” are both innocent and vulnerable, in need of protection.

But if women and children are holding hostages, and deeply aware of their plight, as Schem and other released hostages have described in excruciating detail, should news outlets make that clear to viewers?

This is no ordinary war, and the combatants are not ordinary soldiers. That’s why the language of hostages, including the word “redemption,” matters.

These hostages returned to Israel at a price. As in the days of old, there was a ransom — not money, but a pause in fighting and the release of prisoners with records of violence.

Maybe “redemption” doesn’t cut it. Maybe we should say “bartered,” “traded” or “brought home in exchange for more blood somewhere else.”

Who is being released

I spent a heartbreaking hour watching Israeli victims of prior terror attacks on television, saying that while they supported doing everything to help the hostages, and bring them home, they also thought the security of Israeli citizens mattered, and that certain prisoners should not be released.

No one should forget that Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar was one of the prisoners released in exchange for Gilad Shalit.

And no one should forget the high price of resisting Hamas. Sinwar was in Israeli prison for murdering two Israeli soldiers and four Palestinians, suspected of collaborating with Israel.

In August, according to Agence France-Press, “A military court in the Gaza Strip on Sunday sentenced seven people to death by hanging for ‘collaboration’ with Israel.”

On Nov. 23, in the West Bank city of Tulkarem, two Palestinian men suspected of helping Israel were killed, with their bodies “hung on an electricity pole and later dumped in the trash as crowds called ‘traitors.’”

Gazans are undoubtedly living in awful circumstances. Yet polls show continued strong support for Hamas — 72% of Palestinians believe the Oct. 7 attack on Israel was correct, according to the Palestinian Center for Policy Survey and Research. That breakdown is 52% of Gazans and 85% of West Bank respondents.

All of this makes it easy to avoid thinking about words we take for granted — like “redemption” and “civilians.” But language reflects lives, and language shapes history. We ignore it at our peril.