What New York lost when it lost the Jewish cafeteria

Looking back at Dubrow’s of Kings Highway with photographer Marcia Bricker Halperin

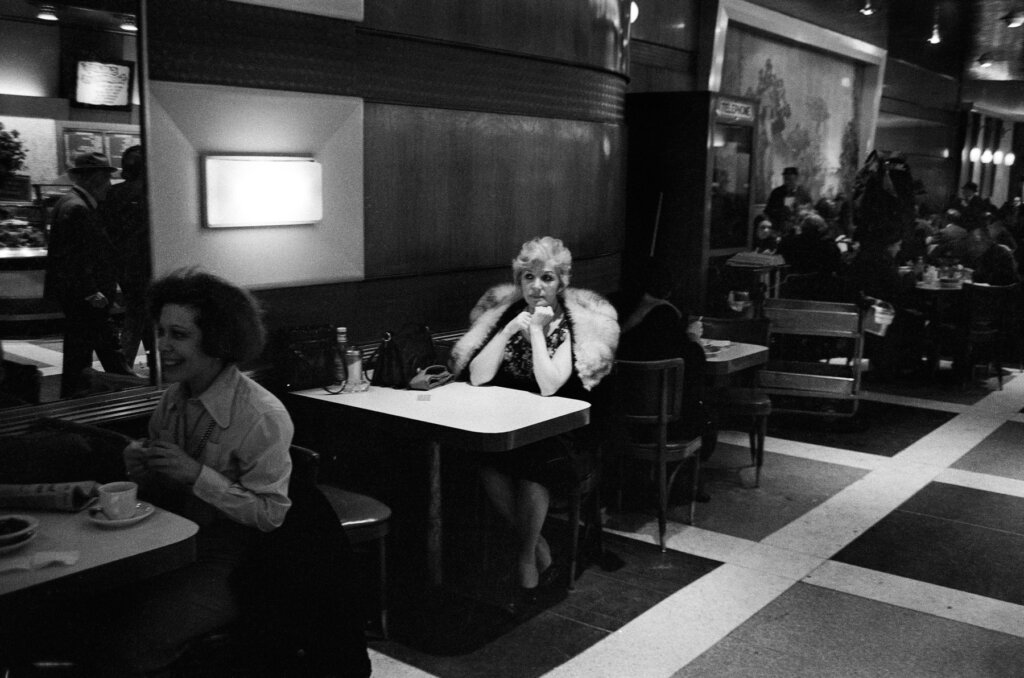

Evening out, 1975. Photo by Marcia Bricker Halperin

There was a time when, for New York’s Jews, the word “cafeteria” conjured up something far grander and more full of hope than sterile lunch counters that serve soggy pizza to elementary school students.

By the 1930s, Jews had embraced their own version of the city’s beloved cafeterias, counter-service restaurants with satisfying, affordable food and no limit to how long customers could sit. Here, one could catch up with friends, read the news, and find love — all while noshing on a blintz or a Danish.

“Conversation flowed freely at Dubrow’s, and it was not unusual for patrons to walk around and greet friends at various tables as if they were at a large private party,” photographer Marcia Bricker Halperin wrote in Kibbitz and Nosh: When We All Met at Dubrow’s Cafeteria, a book of photos she took of the scenes and characters of Dubrow’s, a Jewish institution in the neighborhood of Flatbush where she grew up.

In 1975, Bricker Halperin stumbled into Dubrow’s and was “wonderstruck” by the opulent space and the colorful characters who dined there, she wrote in Kibbitz and Nosh. “It was the most idiosyncratic room I had ever seen. My eyes followed the sweeping, amoeba-shaped ceiling half an avenue to the back where it ended at a sparkling mosaic fountain.”

That chance encounter sparked a years-long love affair with the Kings Highway cafeteria. She spent the next three years photographing what she said she sensed was a “vanishing world on its last legs.” She was right: Dubrow’s Flatbush location closed in 1978.

Her photographs reveal a cast of Brooklyn characters, often elderly and smiling warmly at Bricker Halperin, who, she wrote, “became a celebrity at Dubrows.” Four older men in suits and top-hats sit at a square table in Over-Eighty Club, named for the the informal group that regularly met at Dubrow’s. In Housewives, 1975, two women chat hunched over a table before the restaurant’s grand mural, a marker of a post-war opulence that the place embodied.

Though most of the photos do not feature food, behind the camera, food was part of what made Jewish visitors comfortable.: Dubrow’s may not have did not separated meat and milk in their kitchens, nor did they necessarily elide non-kosher foods like shrimp, but they did serve Ashkenazic treats like matzo ball soup and pierogies while avoiding goyish dishes like baked beans.

Dubrow’s was a haven for Jews, but it was not so for all New Yorkers: In an essay in Kibbutz & Nosh, historian Deborah Dash Moore wrote that “when Blacks and Puerto Ricans moved into Brooklyn after the war, they were not welcomed at Dubrow’s” and faced discrimination citywide. Dubrow’s clientele were “a multiethnic but primarily white crowd,” she wrote — at their Kings Highway location, this meant largely Jewish, Italian, and Irish. .

Dubrow’s was a haven for Jews, but it was not so for all New Yorkers: In an essay in Kibbutz & Nosh, historian Deborah Dash Moore wrote that “when Blacks and Puerto Ricans moved into Brooklyn after the war, they were not welcomed at Dubrow’s” and faced discrimination citywide. Dubrow’s clientele were “a multiethnic but primarily white crowd,” she wrote — at their Kings Highway location, this meant largely Jewish, Italian, and Irish. .

After retiring from a 35-year career as an educator, Bricker Halperin embarked on a mission to research and document Dubrow’s, poring through archives and interviewing members of the family as well as people connected to former staff and diners.

I talked with Bricker Halperin about the people she met at Dubrow’s, whether the cafeteria would appeal to New Yorkers today, and how Dubrow’s reminded her of her grandmother’s apartment.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

There’s a great photo in the book of a side view of a man reading the Forward.

Nobody really noticed — including me — that underneath the Forward was the The New York Times. That says a lot of that generation. They’re clinging to their old world. He still wants to read Yiddish and he wants to know whatever that news is, but he’s also assimilated. He’s gonna read and find out what’s going on in this world.

Did you grow up around the types of people you met in Dubrow’s?

When I started taking photographs, I took pictures of my family a lot. I took a lot of pictures of my grandmother. She was quite a character. She lived in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. And I would go over and look at her white hair, you know, with the light on it — the wrinkles. She was 80 or so, but she just really appealed to me. And she lived in this old world apartment with old, dark, heavy furniture.

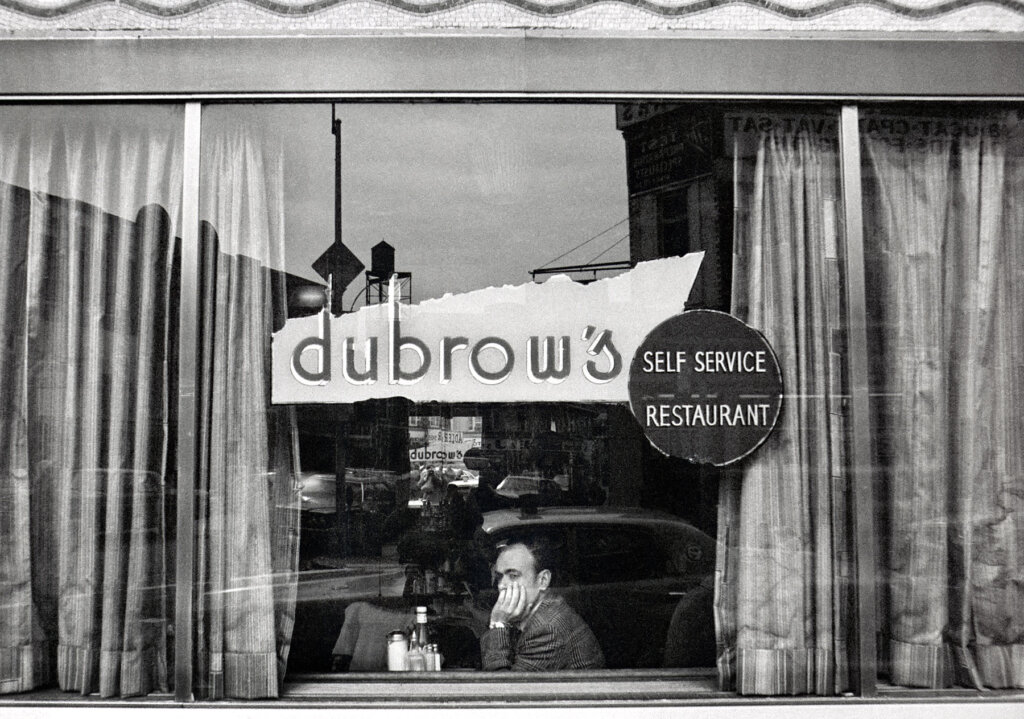

So I’m photographing that at the time, and I’m studying the photographers of the Photo League, who had documented changing New York, like Jacob Riis, who had photographed the Lower East Side in How the Other Half Lives. The idea of documenting your neighborhood.

And so I go out, and I’m documenting the streets of Flatbush, and the window of Dubrow’s. Then it got too cold, and I went inside the cafeteria and I saw this old world — like my grandmother’s apartment — except it had modern chrome and mirrors.

I had a feeling New York was changing. And I did see other cafeterias in the city that I went to, close. And I felt like I was racing the clock.

Are there any conversations with patrons of Dubrow’s that have stuck with you to this day?

Are there any conversations with patrons of Dubrow’s that have stuck with you to this day?

There was this one very professorial kind of guy. He wore a beret. He wanted to teach me about photographers. Now, understand, it’s not like you could go to the internet. The Strand bookstore used to have photo books remaindered on tables; there were some magazines; I learned about photographers in school. This one gentleman took it upon himself to send me typewritten letters where he talked about different photographers. Not only am I learning about Eddie Fisher and old movie stars — vaudeville, they used to talk about — but now I’m even learning about my field.

Otherwise, the conversation was general. There was some political debate, of course. And they would talk about how unsafe the city is — drugs, or whatever.

But he stands out, because, you know, he taught me stuff. I have the letter he sent me about W. Eugene Smith, the great photographer.

Lots of women with heartache stories.

Any in particular?

Oh, no-good husbands who left them; no-good children who left and moved out of the city. I mean, it was a kibbitz place. Not-that-earth-shattering conversations, but company. And someone to let a little bit of your heartache on.

I think a lot of the older people there, they always came there with hope that they were going to meet somebody, because it was a very social environment.

They used to have dances in Brooklyn for divorced people. They were a big deal back then — the “parents without partner dance.” And they would go to Dubrow’s after, because if they didn’t meet anyone at the dance: One last chance! We can go to Dubrow’s!

In your essay you wrote that you had a friend whose Chinese father became a night manager at Dubrow’s. Were there a lot of non-Jewish people there as diners or staff?

That neighborhood was probably equally Jewish, Italian and Irish. A middle class neighborhood. But that’s it. I mean, let’s be real: Brooklyn in those days — [the area around Kings Highway] was a white neighborhood. There was a lot of white flight from Brownsville to Long Island.

It was maybe half Jewish. But, you know, it always kind of felt like it was a Jewish cafeteria because it served gefilte fish, it had matzah — but it also had shrimp salad.

Was it a type of place where you’d see the Italian, Irish and Jewish people hanging out with each other?

Yeah. The over-80 club that met every morning, there was definitely a Jewish guy and an Italian guy in that group. They were a mix. But you’re talking about middle class Jewish, Italian and Irish families. So, you know, it’s not that diverse.

And the staff?

There were two groups. There were the unionized guys behind the counter. Some of them wore their local 325 buttons to talk union stuff.

Now, a lot of the busboys on the floor would have been immigrants from all over the world, who found their way to work there, somehow.

They really wanted photos showing them working in America. One guy, he would run behind the counter and put his hand on the shoulder of one of the union guys, like, ‘My buddy!’ And he’d send it back home, like, ‘Hey, I’m working with the Americans behind the counter.’ It made him feel very important, you know — to show the family success.

We’ve been talking about the kibitzing part of it. What about the nosh part?

Everyone would have a coffee and a roll with butter because it’s one dollar. Coffee and a danish you could do for a dollar. There was a lot of that going on. You could spend three hours, coffee and a danish, handicap your horses, get some tips.

There was a big water fountain in the back where you could drink water. At one point, it had seltzer.

Now, that’s not to say that people weren’t filling their trays with a full meal. There were meat sandwiches and, you know, cooked chicken, and potatoes, spinach, and then coming back to cheesecake for dessert.

What do you think was lost with the closing of Dubrow’s and spaces like it?

Sometimes you hear it said that “cafeterias were democratic environments.” Anybody could come through the door who had a quarter. Of course, in New York, it’s expensive to eat out otherwise.

So there was that. And the space: Cafeterias were very large, and beautifully decorated. Because, as it turned out, in 1939, Benjamin Dubrow had made a lot of money through the Depression with this other cafeteria somehow, and put it into investing in this. It was good times again. He painted this mural — no expense was spared. It was opulent for Flatbush.

Do you think that Dubrow’s would appeal to people today?

First of all, a place like Dubrow’s couldn’t survive — the space, and people sitting, with the price.

We have coffee shops all over the place where people hang out. Usually you come with your friend or your laptop. There’s not that much in between. I think that’s what they’re trying for — ”We want to be the community place.” Everybody wants a place like that.

Our tastes are so much bigger today.

In the space where the Garment District’s Dubrow’s was is now a food court. And of course, there’s a sushi counter. It’s much more international. We’ve outgrown what a cafeteria counter could have possibly provided. But at Dubrow’s, I got to have my first shrimp salad!

Do you think the social culture that made Dubrow’s special is harder to find now?

Yeah. I do. And there was a trust there because we were all of that community. I took rides from people I met at Dubrow’s. This is the summer of the Son of Sam, and I’m letting guys walk me home. It was the New York of kids playing in the streets, of people on stoops.

Now, I think people are searching for community and trying to do it in little ways. It’s a much more transient city. People were there, they went to school in their community. They worked, shopped in their community. We don’t anymore. We’re all over the place.

Maybe that’s the bottom line: People feel the need for personal connection with people — the opportunity for chance meetings. The idea of striking up a conversation with someone on the subway. It doesn’t happen as much anymore.