What we mean when we say ‘never again’ depends on where we’re from

An Israeli-American reflects on assimilation and antisemitism after Oct. 7

At a ceremony for Yom HaZikaron in 1962, Itamar’s grandfather (third from right), who served as the chairman of Yad Vashem, stands next to Prime Minister David Ben Gurion (second from right). Courtesy of Itamar Kubovy

My first American Passover was in Connecticut in 1973. We were newcomers to this country, recent immigrants from Israel, and the family who invited us saw it as a mitzvah. The hostess was also an immigrant, a survivor of the Holocaust. The other guests had ancestors who came through Ellis Island at the end of the 19th century. We returned to this Seder for years; it was my family’s first real exposure to Jewish America.

For these Reform Jews who had ascended into the suburban middle class from the tenements of Brooklyn or the Lower East Side, Passover seemed mostly to be a day of gratitude for such success — like Thanksgiving, except with matzah, maror, and kugel instead of cornbread, cranberry sauce, and stuffing. The Seder was a chance to celebrate how well Jews in America were doing by reminding the children that it was not always so.

This was done by holding up a Seder plate and explaining that each item — parsley, horseradish, a roasted egg, charoset — represented some aspect of Jewish suffering. The shank bone in the center, always a bit shriveled, symbolized the strong arm of God that helped end that suffering. Next, came the Four Questions and a haphazard retelling of Exodus. Then, dinner.

I recall, too, a kind of Passover parlor game where we went around the table, youngest to oldest, listing injustices in the world that deserved more attention. Some were personal, others political: A Little League coach who made all the Jewish kids run around the field not once but twice before the start of practice. A B+ in math from a teacher who pronounced Amanda Brownstein’s name with an exaggerated shteyn. Civil rights, unequal pay for women, Vietnam. Older guests added historical traumas: the Crusades, expulsion from Spain, pogroms in Russia and Poland.

The list always culminated in the apotheosis of all our afflictions: the Holocaust. Someone — usually a recently divorced uncle, perhaps having brought a new, non-Jewish girlfriend — would quiet the table to pose a question: What was the most important lesson from the Holocaust? When no one answered, he’d repeat it. With all eyes focused on him, the uncle would intone: never again. The adults nodded somberly in agreement as the uncle lowered his head, closed his eyes, and quietly repeated: never again, never again, never again. I remember the kids looked up at their parents, and then at each other, wondering when they could have ice cream.

To most of the people at those 1970s Seders, the Holocaust was something that happened to other people back in the old country. They’d learned about it in Hebrew school, experienced the horror in the third person, confident that while the genocide was taking place in Europe, the U.S. had remained a safe place for Jews. Their tone was caring, but contained an air of pity for those whose families hadn’t gotten out. There was a sense that American Jews — the successful, unthreatened branch of the tribe — had agreed to chip in and help in part to compensate for the victims’ bad judgment.

The way my father saw it, lecturing as he drove me to flute lessons in New Haven, American Ashkenazi Jews could be broken down into three groups. There were those few who came to the U.S. in the 19th century, mostly from Germany, made money, and assimilated completely. Then there were the nearly 3 million who flooded in at the beginning of the 20th century, who fled antisemitism in Eastern Europe only to experience it again as new immigrants; these maintained a strong Jewish identity even after a generation or two and supported the idea of Israel. The third and smallest tranche, according to my father, was the one to which my family belonged: the “lucky” few who made it out of Europe after Hitler came to power, torn from their large families who clung too long to old-world values and paid the price. I remember feeling ashamed that our ancestors had trusted too much and called it wrong.

From the Holocaust to Yad Vashem

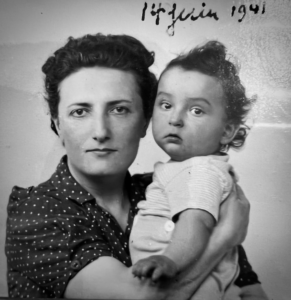

My father was born in a convent near Bordeaux after his parents and 18-year-old sister escaped from Belgium in 1940. They crossed the Pyrenees into Spain, then trekked on to Lisbon, where they bribed their way onto a ship to New York. For the next five years, my grandparents tried to save their relatives, friends, and neighbors trapped in Europe.

Operating out of a small apartment in Brooklyn, they wrote letters to Congress and lobbied allies in Europe, figured out train routes and tried to arrange visas. Their efforts were in vain — all but five of their 40 relatives were killed in the gas chambers. In 1946, my father’s father, Aryeh Leon Kubovy — then Kubowitzki — became the Secretary General of the World Jewish Congress, in charge of global rescue operations for the displaced. Two years later, the family moved to the new Jewish state, where my grandfather became the head of Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial and museum. After his 1966 death, a street in Jerusalem was named for him.

I was born in Jerusalem 22 years after the liberation of the camps where my relatives were murdered. But I never voted there or served in the military. My father moved us to Illinois in 1971 so he could do a postdoc in psychology. We moved to New Haven in 1973: dad was a professor at Yale, mom taught Hebrew school in the nearby suburb of Hamden, and I started first grade. My parents came to expand our horizons, not to save our lives. Still, we had come to the U.S. from the burnt side of the ocean, and I felt I had to hide my family’s scars to fit in.

I yearned to be like that uncle at the Seder who said “never again” from a place of confidence. He knew antisemitism remained a threat and that Israel was embattled, but he was convinced that in the U.S. Jews had finally found a place that would protect us forever. Even at a Seder, he was an American first, then a Jew. “Next year in Jerusalem,” was said with a wink, imagining a vacation touring David’s tunnels or tucking a note into the Western Wall, not a return to live in the promised land or fight for its survival.

I envied that wink, envied the uncle and the others at the Seder for having ancestors who made the right choice. I could never assimilate if it meant thinking about antisemitism only when we chant “never again” at Passover.

But I also felt that their confidence was mistaken. It went against the most foundational lesson of Jewish history: that a Jew is never safe. Jews in Berlin, Paris, Rome, Brussels, and Vienna had also felt secure for a very long time. This unquestioning trust in America seemed dangerous.

To my family, “never again” was self-recrimination for not having been able to imagine the horror of the Holocaust before it happened, for misjudging how long we had before we could no longer escape. We were suckered into our own genocide, and we were never able to forgive ourselves for it. Shame on us for believing that the administrative, financial and judicial systems of society we helped build and manage would protect us.

‘We have only us to save ourselves’

Trust crumbles like an avalanche; it starts with a quiet rumble. Small, insignificant relationships fall away first, followed by larger, more threatening betrayals, and then it’s too late. The gradual collapse of relationships that preceded the genocide — experienced one betrayal at a time — must have destroyed every deportee before they boarded the train.

None of these betrayals compares to the rupture Jews had with God. Many remained forever estranged from their faith, unable to forgive what was allowed to happen. My uncle on my mother’s side, a lawyer in Israel who encapsulates pain in aphorisms, reminded me of this a few months ago, as the new war broke out with Hamas. “During the Holocaust, we believed God would save us,” he said when I called to ask how his son — a young soldier — was faring in the war, “We saw how that turned out. Now we know we have only us to save ourselves.”

I understand why European-descended Jews living the direct legacy of their family’s destruction might teach their children to mistrust early death. In this Jewish world from which I came, mistrust was the 11th commandment, the key to Jewish survival. “Never again” wasn’t a memorial for Jewish suffering, it was a preparation for its return; a promise to keep Jewish children scared so they would stay alert.

“Never again” meant learning to recognize the moment when the non-Jewish majority suddenly sees us not as an integrated and vital part of society, but as a secret, nefarious tribe trying to take it over. This kind of thinking means that however old or rich you may be, you must always have an escape plan, a go bag — a wad of bills, a few pieces of jewelry, a small album of childhood photos, and as many passports as you can possibly acquire.

To the assimilated Jews I grew up with in Connecticut, and to most Jews across North America today, this level of mistrust seemed unreasonable. In the U.S., making a stink over antisemitism was unnecessary and embarrassing; seeing it as a serious threat seemed paranoid. Antisemitism was a problem abroad, in distant places where Jews were always Jews, never fully citizens of the country they inhabited. Here, they were fully naturalized: Americans who just happened to celebrate Passover instead of Easter.

These two “never agains” — one that assumes the horror will return and we must be prepared, and one that allows us to relax into our Jewishness as one of America’s many tribes — are irreconcilable. No one is comfortable around someone who feels threatened. But Jewish compliance — staying polite, waiting to get all the facts, and letting the system do its job — costs time that could make escape impossible.

An inner nightmare made real

The Hamas attack on Israel last October was staged to remind Jews of the Holocaust: ovens, dismemberment, rape, immolations, and door-to-door executions of people in their beds. Like the Nazis, these terrorists documented what they did. Only this time, it was not historians who recovered evidence after the fact. These killers posted high-resolution close-up views of the snuff-film cosplay as it was unfolding, as if it were a TV pilot for what a future genocidal project might look like.

The nightmare that rests in all of us was made vividly real: “never again” happened, live on social media. The state of Israel was founded to prevent future attempts at Jewish genocide; on Oct. 7, it failed its reason for existence.

Perhaps I am naive, but the explosion of explicit calls for the elimination of Israel in the aftermath of the attack caught me by surprise. I was particularly shocked by the blurring between criticizing Israel’s policies toward the Palestinians and its existence as a Jewish state.

I understand why Israel’s response to the Hamas attack, like all of its political and military actions, causes violent disagreements in the diaspora. I get why some millennial Jews, two generations further from the Holocaust and disconnected from Israel in every way, see Oct. 7 as a desperate act of resistance executed in the service of a morally justified, ongoing struggle for Palestinian independence. But I did not expect that underneath the banner of Palestinian justice, millions of people in the U.S. and around the world would rush into the street to call for the elimination of the Jewish state, and by extension, Jews. That they not only wanted to punish Israel for what it has done to Palestinians but also to combat Jewish power.

My American Jewish self is telling me to view this uprising through the eyes of my liberal American values – that words are not actions, that anti-Zionism is not necessarily antisemitism, that even antisemitic screeds are different from antisemitic violence. This liberal Jewish lens insists that we can rely on democratic systems and principles to protect us.

But my never again alarm is ringing loudly. I had heard about the lava-spewing eruptions of the volcano of antisemitism all my life; now, I have lived through an eruption that reveals hate at scale. I am reminded of the words sung at the Passover Seder: “For not only one has risen against us to annihilate us, but in every generation, they rise against us to annihilate us.” Is this how it begins?

Never again

It has been 53 years since my first American Seder. During this time, I have aspired to the old uncle’s sense of security as a mark of being fully American. I married a woman whose large Ashkenazi family prospered in New York for the last century and has a Seder much like the one I attended in Hamden as a boy. My children feel deeply protected as Jews in America. None of the Jews close to me watch their backs. I hope they are right; no one would deny that faith in a safer life is a better life.

Yet the public tolerance for antisemitic speech in U.S. cities and on college campuses since Oct. 7 gives me a nauseating sense of vindication. I worry that the mistrust I was taught was justified. I wonder if the peaceful history of Jews in America has created its own maladaptation, a blindness like the one that made our predecessors in Berlin, Paris, Rome, Brussels, and Vienna fail to see the oncoming threat. The last 100 years have been good to Jews in America, but the last 2,000 have ended badly for Jews everywhere, always.

I was talking to a friend about Israel the other night, and she could not understand why Jews ever thought it was a good place to go, given the hostility of the surrounding neighborhood. We went, I know, because, as dangerous as the Middle East seems, it was worse everywhere else. From where we sit here in the U.S., 75 years and an ocean away, it is hard to understand that kind of choice. But it is the reality of our history — again and again, in every generation — that we should not allow ourselves to forget.