Claire Messud did not realize she was writing such a prescient novel

‘This Strange Eventful History’ is a sort of generational family saga, but its consideration of occupation and diaspora seems particularly timely

Claire Messud’s latest novel is ‘This Strange Eventful History.’ Courtesy of Claire Messud

Claire Messud is, for me, the epitome of a thriving working writer in America, her success evidence of a literary world, a system that often does not reward the most deserving of artists, for once getting it right. She is a true artist, who also sells books, not least her bestselling novels, The Emperor’s Children and The Woman Upstairs. Messud is also a formidable critic, a true literary citizen, writing saliently and consistently about the work of her global peers — until recently, she wrote a monthly “New Books” column in Harper’s Magazine.

Messud’s newest novel, This Strange Eventful History, examines a fictional version of her own family, including her grandfather, who was one of the French nationals occupying Northern Africa during the period of French rule, her father, and his never-married sister, who have been flung into the diaspora.

In ancient Greek, diaspora means “to scatter about,” and the Cassar family of the novel were indeed scattered, their post-Algerian War for Independence lives spent in Toronto, Sydney, Buenos Aires, Toulon, and Cambridge, Massachusetts. But it’s Algiers that many of these characters long for: its light and its proximity to the sea, the bakeries, the language, and domestic life before the war. But an inheritance that has been wrested away is also a legacy, even as Messud’s generation (whom we see through the character of Chloe) is heir to a lost identity. The novel throws into question what occupation means for the occupiers who have not yet lived through history and are making urgent decisions in real time that history will not smile upon. Messud investigates the Cassar family with both intimacy and a broad sweep, traveling across an ever-changing world, whose past conflicts have a profound effect on the world we now see shifting before us.

It feels like Messud has needed to live every moment of her life to write such a consequential novel. The book is masterful in its handling of time and perspective, a love letter to both the past and literary history, testament to fiction’s truth and timelessness. Through her lucid and elegant prose, Messud guides the reader through this complicated, nuanced and riveting generational story.

I spoke to Claire Messud via Zoom from her home office in Cambridge, a place she is now packing up, downsizing her domestic life to give more room to her writing life.

Jennifer Gilmore: Your book investigates your own family’s generational experience in a diaspora. Francois and his family’s dispersion from Algeria, and then from France, made me think of the Jewish diaspora. It also reminds me of Salman Rushdie’s Imaginary Homelands, that seminal collection of work that has that same ache for home, even though home is a complicated place. I think we write about the past to somehow say something about the now through the prism of history. I know you’ve been working on this novel for a long time, but I’m wondering if the political aspects of it — I am thinking about colonization and decolonization — or the ideas of history are speaking to you about the present as well. So why now?

Claire Messud: Yes, so to start there, it’s strange that there are these questions of, if you will, colonization, decolonization, which seem in this moment to be a focus around the conflict in Israel and Palestine. For the first time that I know of, that conflict is being framed in this country directly in that way, or has been laterally, and that’s been strange but also resonant. And it was not something that was on my mind obviously in the writing of the book, which is about my family history. History gets flattened into just dates and facts and anonymous narratives of peoples and when I have tried to explain, my father’s family was on the wrong side of history, it was absolutely right. Algeria should be an independent nation, and the horrors of colonialism are legion and rife.

From the position of these very devout Catholics that my grandparents were, there was a sense of mission — and it sounds so appalling now — but then it was enlightenment, like: “We are bringing French education and French culture and French everything you know, roads and lights and running water.” It wasn’t framed for people 100 years ago, or not for most people 100 years ago, as oppression. Partly what I was trying over the course of the book to convey is just how one’s beliefs at any given time shape our understanding of the events. And so that’s a question: If you’re super-religious and you’ve been given a green light by the head of your religion, there’s no hesitation, right? Whereas if you’re outside that bubble, that cone of faith, it’s like whoa, that’s insane.

I was trying to make people understand what it was like to be my grandparents, whose own ancestors had been over a hundred years in Algeria. And when you read their letters from when they were young, they talk about [how] they loved the land, they loved the flowers, they loved the birds, they loved the light. They believed in building something there that, in some absolute sense, they had no right to, it wasn’t their nation. I’m not in any way defending the French colonial state in Algeria but it seems to me, as writers, we can only capture what peoples’ realities are so that somebody who is ideologically at the opposite completely, who has never been able to see a French colonial person as a human being, could read my novel and suddenly say, “But that is a human experience.”

I feel as though that state of diaspora is something that people with very different histories have in common, and maybe a place where people can find understanding. Maybe.

Francois refers to himself sort of as a wandering Jew. He sees himself as a wanderer. You’re putting these characters’ consciousness on display: who they were, and just who and how the notion of home in a diaspora becomes family. Did you have to confront any family myths? I’m wondering if there was any friction between what you know, or what you researched and found out versus what you’ve internalized as a member of the family?

That’s a really good question. I’m wondering if you’re asking it in relation to anything specific.

I guess I’m asking in relation to what you’re saying about the word: occupation. You’re building that world for us as a writer. I’m wondering if that world was built for you in the same way. It’s not a trick question!

So humanly in my family life, no. It’s worth saying that my father never said anything about his upbringing. Eventually there were a couple of childhood stories, just local stories about him and his sister playing, but he never said anything about Algeria ever.

Then how do you know all this?

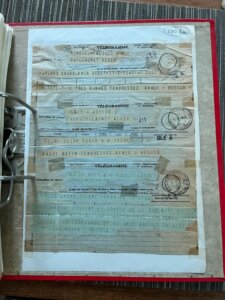

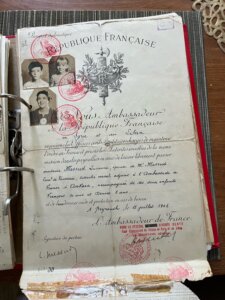

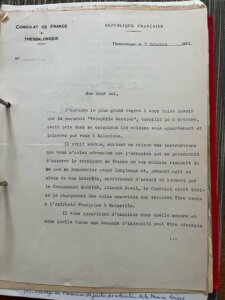

If I had been a different person, I could easily barely be aware of it. My grandmother lost her memory, was demented when I was very young. But my grandfather was somebody who was incredibly present in our lives, and he spent all this time in his retirement writing this memoir of this time, which is very specific: 1928, when he and my grandmother got married, to 1946, which is the end of the war. 1200 pages! I have in the garage the five binders, all handwritten with everything stuck in, and photographs, telegrams. So that was a huge chunk of it in terms of understanding them, and then their letters.

They were all letter writers. I have from the time that my dad was at Amherst. I don’t have his letters home, but I have all the letters that his family wrote to him: his sister, his mother, his father, his barely literate aunt. I so lament the loss of letter writing. It’s so much somebody’s voice. It’s not on show. It’s not for the public. It’s how they’re thinking and who they are and what they choose to share with whomever they’re writing and the funny little details. I could hear the people they were before I knew them, before I was alive, in those letters. It collapsed time.

And there are other letters like the letter at the end of the Salonika [Greece] section, that’s a letter that my grandfather’s ADC [a military officer who is personal assistant to a senior officer] wrote to him, which was like, ‘Okay, you’re not going to go, but I can’t not heed the call of De Gaulle.’ But then to think of this moment where you don’t know how the war will turn out. Grandfather doesn’t know if De Gaulle is a quack. He doesn’t know where his wife and kids are; he hasn’t heard from them. In May of that year a journalist came to Salonika and went out for lunch with my grandfather, and said, “Everybody in Paris needs to believe that the army is coming. Please, can you confirm for me that that army is on its way?” It was a totally non-existent army. And the journalist hoped he would say, “don’t worry, don’t worry, of course, we’re not disorganized like that. There’s a huge army on their way.” And it was literally fake news.

That moment was in particular where I felt, “Oh, my gosh, he’s making the wrong decision because history hasn’t played out yet.” And also, he’s French. You capture being in that moment so well.

I think if we try to imagine: how would we behave in such a moment, right? We can’t know, we have no idea, but just that idea that you really don’t have the facts.

You’re talking about going through all these family archives, and it’s so lovingly done. I consider you a fairly private person. I don’t want to call you a private writer, because I always feel very welcomed into your books, but you are more contained, and your writing is so elegant and precise, and it’s still elegant and precise, but it’s more sprawling here. There’s more openness to it. I apologize in advance for this question, because I know that you’ve suffered a lot from both of your parents being recently deceased or relatively recently, but I’m wondering if that freed you up to do this in some ways.

I certainly couldn’t have done it when they were alive.

Like you couldn’t have gone through the material, or you don’t think you could have freed yourself as the writer to write?

I couldn’t have written it when they were alive. I’m imagining characters obviously, it’s not them, and there’s that fictionalization, but I’m imagining effectively what it was like to be them in some way, and I wouldn’t have done that while they were living. We were a small family. My sister is the only one with me here, and she’s read it, and she said she feels good about it. There’s lots of reasons why I couldn’t have written it sooner, but also I think of my grandfather’s memoir, he called it “Everything We Believed In.” There’s this moment in it, where he includes a letter that they wrote for their children — my father and my aunt — if my grandparents should die in the war. It’s very sort of Frenchly orderly, and my grandfather says, “This is what you should know about us. We are Mediterranean, we are Latin, we are Catholic, we are French, in that order.” That’s basically genus, species. We are Mediterranean, we are Latin, we are Catholic, we are French, and I am officially none of those things, right? So, there is this way in which he was giving us some sense: This is where you come from.

And I became aware, in a practical sense, around the time of Trump’s election, that the world I grew up believing in, everything that I believed in had become historical in the same way. The very fact of my parents’ marriage, which was sort of weird and radical at the time in the 50s, their post-war faith, like things had been to the nadir, the earth had been to the worst possible place, but now the Phoenix rising from the ashes, and we were going to build a better world which was a capitalist world inevitably, with international cosmopolitan boundaries coming down, hybridity, marriages across cultures and races, and the opposite of tribalism and the opposite of nationalism and the opposite of specific identity politics. Just being like, “Let’s blow it all open,” which you can see the 70s in some way sort of as the logical eventuality of that time of rebellion.

With that was also still a teleological belief that the world could get better, and that we would try to make a better world, and if you think back at the moment that we all lived through in 1989, where we were like, “Look, it’s happening! It’s happening! The better world is on its way!” And then you can look again to the Arab Spring and be like, “Look, it’s happening!” And I think at this point, in 2024, it’s just pretty hard to feel like it’s happening.

There was an optimism, and there was a faith, and there was a sense not of an atomization, but a “We can do this together” At the same time, my father was a cog in an international corporate machine that was involved in the massive extraction of the minerals and resources of developing nations. This site, Weipa in Queensland, Australia, where they mined bauxite for 40, 50 years, and now it’s Rio Tinto that owns it, and they’re returning it to the Aboriginal people and while I haven’t been there, I can’t help but wonder, what are you giving back?

I’m interested in this investigation of marriage in this book, too, and the way that marriage becomes the home. Family does. There is a beautiful marriage here, and it only works because the roles are so cemented, and then we get the next generation, the complications of the second part of the century, where the roles change, and we have more choices, and it gets more complicated. I feel like we write generationally to see the psychic effects of history and the effects of what the other generation has done to us, but I’m wondering, your take on that. Were you intentionally looking at marriage in all these different ways?

So yes: There are the events, and there are the narratives and the myths. The myth of our family always was my grandparents’ perfect marriage. They never had an argument, and my mother hated my grandmother, not because my grandmother was ever anything but sweet, but precisely because, enough with this saintly bullshit. So, there’s the broader thing which is like, “the perfect marriage, the perfect marriage,” but the actual factual truth of their marriage is a little bit disturbing. But it is also the perfect marriage. Hopefully, your reader will have some sort of colonialism moment where they’re like, “Oh, people going through colonialism being like great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great!” And then suddenly being like, “Oh.” Right? It’s both of those things together. You can go your whole life with a belief that something is a great thing and just not have all the facts there, or your perspective is altered by your faith, a set of beliefs that are so internalized, you don’t even know they’re beliefs.

The whole family changes.

The whole family changes.

So why not a memoir? I do feel like I know the answer to that, but I want you to tell me. It’s obviously very novelistic: the dramatic distance of the beginning of the novel. And we think it’s going to be this sweeping novel, which it is, but we also get closer and closer narratively speaking. That distance between the reader and the characters gets closer and closer, and to the point where it turns into first person.

I’m a novelist, not a memoirist. I read somewhere that it says in the Torah that you can’t raise pigs on the land of Israel, and my understanding is not that there are no pigs in Israel, but that they, the pig farms, have the pigs on pallets. Maybe it’s not true. We don’t need to think of it as Israel. You can think of pigs on paletts anywhere. My point is that’s what fiction is. Fiction is: You raise the space between the history and the story. I’m interested in people. I’m interested in motivations and psychologies and relationships, like in Zadie Smith’s wonderful essay on “The Imagination is Free,” in the New York Review of Books a few years ago, and she basically says, “As a kid, I just imagined being other people the whole time.”

For me, that act of imagining what it was like to be these people whom I loved but had, as we do, complicated relations with over many years. But if you go back over time, it was complicated. Politically, not only am I not Catholic and not Mediterranean, but I was also marching in left wing marches in my youth, so I was in every way far from my grandparents but loved them and I don’t think they were bad people, and so I didn’t want to observe them from my perspective. I wanted to try to understand them from within their own skins, and with the beliefs that they had.

The other thing I would say about the change in the narrative over time is that it was very deliberate. It’s about getting closer to what is known, for the writer, intimately known, but it’s also about the evolution of narrative, over time, and that sense that just in the broader world, this for me is also about the whole second half of the 20th century. It’s about the fact that just by living, you end up in weird, historically significant experiences but also, narratively, there’s this evolution towards greater interiority, towards auto fiction eventually.

[W.G.] Sebald said in a conversation with James [James Wood, Messud’s spouse] not two years before he died, “We can’t write in the third person anymore. You can’t. All we have is the first person because all those great certainties, those 19th-century certainties about narrative that would allow you to have a godlike perspective, they’ve dissolved. We only have our individual subjectivities.” And so, in my mind, at least, the narrative structure of the very earliest, certainly the 1940 sections, is much more 1940ish, and I hope that there’s some sense of the fluidity or evolution of narrative form as well as everything else.

That space that you’re talking about, which is why I do think fiction might be harder to write, the analysis that you’re doing is implicit in the consciousness or in the metaphor. A memoir is two stories: the thing itself and then the analysis and reflection of the thing, and in fiction we have to do it together. You’re really making the reflective aspects, the analysis of the world that you’re talking about in these characters, and that’s part of what makes them so complicated and so beautiful.

I would just also say, I feel strongly, and it may not be a popular perspective in this exact moment, but I feel it strongly about the literary endeavor that I’m with Chekhov. It’s not my job to tell you horse thieves are bad people. It’s my job to tell you what this horse thief is like.