The saga of an Israeli hostage inspires a song of celebration and defiance

‘Rimon’s Song,’ by David Brinn and Libbytown, tells the story of Rimon Kirsht Buchshtav’s captivity and homecoming

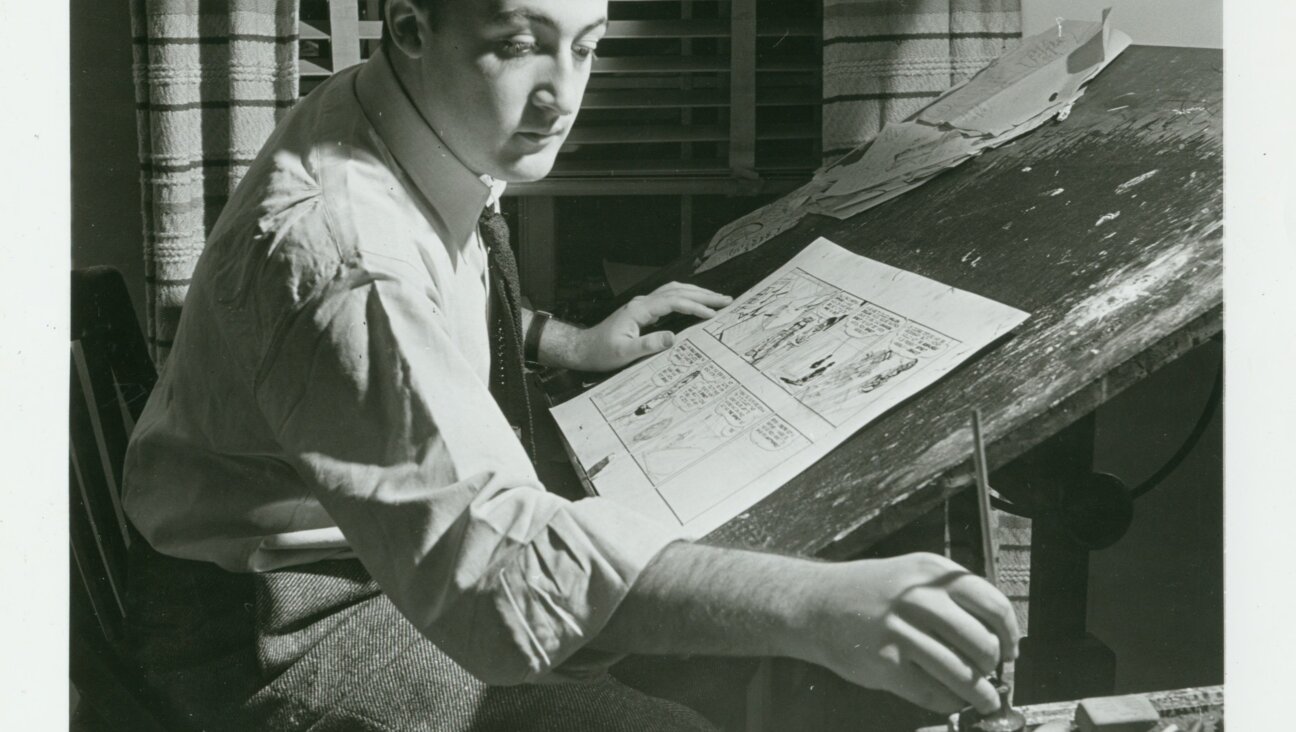

David Brinn, who wrote the lyrics to ‘Rimon’s Song’ is a senior editor at the Jerusalem Post. Courtesy of David Brinn

The protagonist of the song is a captive. “We’re sitting in a darkened room, can’t tell the night from day,” the vocalist sings. “But if I get out, I imagine just what I’d say.”

When she’s told she is being released she wonders if it’s a cruel ruse: Is it freedom or a trap? It’s the former. And, as she’s being escorted out of hell: “Only with a warm embrace did it seem like it was real / I hope someday those left behind can feel what I feel / A few more steps and we’ll be coming home.”

The voice belongs to Jane Brien. The haunting, sparse music is played by her husband, Joe Brien, the two being a Portland, Maine-based duo that records under the name Libbytown. The melody and lyrics were written by their friend David Brinn, a senior editor in the Jerusalem Post, in his home studio in Ma’aleh Adumim, a Jerusalem suburb.

And the woman whose inner thoughts they are striving to convey, is Rimon Kirsht Buchshtav, who was seized from Kibbutz Nirim by Hamas terrorists during the Oct. 7 massacre and kidnapping spree.

The tune is called “Rimon’s Song,” and it, with the accompanying video montage by Brinn’s son Koby, is slated to be on the big screen at the weekly Bring Them Home Now rally in Tel Aviv Saturday night. The rallies have been gathering up to 30,000 people. Kirsht Buchshtav, 36, spent more than 50 days in captivity. She was released in late November as part of a temporary ceasefire negotiation. Her husband, Yagev Buchshtav, 34, remains in captivity.

Brinn, who moved to Israel in 1984 when he was 25, built a studio in his home during the COVID-19 shutdown and started getting more serious about songwriting. “In November,” he says, on the phone from Jerusalem, “when a number of hostages were released, everyone was riveted to the TV, watching it unfold live, watching when Rimon was taken out of the Red Cross van by her Hamas captor. She went up to him face-to-face and stared him down. No fear at all. Amidst this tragedy of being captive for two months to still have that inner strength. She’s telling the older captive, who she has her arm around, ‘Walk tall, be proud, we’re almost home.’ That’s what I imagined her saying.

“The image stuck with me and it was broadcast over the news over the next few days and she was like a folk hero. I started thinking to myself ‘I wonder what’s going through her head, what she went through’ and the song was formulated through that. It took a couple of months. I laid down a basic track in my rudimentary style and I thought I had something special.”

He also knew he needed a strong female voice to sing it and a musician better than himself to flesh the song out, so heturned to his longtime friend, Joe Brien, someone he’d been exchanging demo tapes and links with for decades. (They grew up together in Portland and formed a band as kids called The Frog.)

“I love Jane’s voice,” Brinn says, “sort of a combination of Stevie Nicks and an Appalachian country sound and I thought she could do a nice job. Joe listened to it and said ‘We both love the song. Do you mind if we record the whole thing?’

“To be the song voice of someone’s experience you’ve got to be really careful,” Jane Brien told me. “You’ve got to be true to them, true to the experience. The song is definitely there to bring humanity to her story.”

Brinn said he felt a “natural transition” from writing text to writing lyrics “because you’re trying to choose words carefully, make sense, and tell a compelling story. My antecedent in writing lyrics that do that has always been Bruce Springsteen, who tells so much with few words that open up the listener’s imagination.”

Before hearing Brinn’s song, Jane says she began to feel somewhat disconnected from the hostage situation, which seemed as if it were fading away from view or being minimized in the wake of Israel’s offensive in Gaza.

“I feel people are forgetting because it’s been going on so long,” says Brinn. “So, this was a way to keep it in the public eye. The song is starting to get some traction in Israel. Hopefully, some big stations in Israel will pick it up, but my focus is more on the American audience.” (Brinn says he’s heard maybe half a dozen other songs dealing with the hostage situation, but all were sung in Hebrew.)

Joe used Brinn’s basic arrangement, but changed the key and worked with the phrasing. Jane shifted the melody around slightly. “She was letting it go around in her head,” says Joe, “and finally one night she comes up and says ‘I’d like to try singing that now.’ I put up the [backing] track and let her take four or five passes at it. I let her go for it so she could feel it uninterruptedly.”

Jane nailed it.

“I wanted a canvas Jane could put her voice on without a lot of other extraneous images in it,” said Joe. “I did put some electric guitar in the background toward the middle-end of the song to bring the dynamic up a bit.” Joe ended up doing 34 mixes of the song before he was satisfied. He sent it to Brinn and he, too, was pleased with the result.

There’s a duality to the song and video, a mournfulness cut with a glimmer of celebration and defiance. “I played a basic acoustic strumming track,” Joe said. “I dropped my E string down to D. It gives it that low drone, a reverb-y, weeping slide guitar. When you hit an open note with that low D chord, it’ll ring forever.”

“My voice is really weird.It cracks a bit,” she added. “[The song] is celebratory and it’s sad. Her husband is still a hostage, so half of her heart is not with her. She’s in the moment and she’s being strong in this moment for others. She’s very much a warrior.”

Once Brinn finished writing the song and the Briens had recorded it, he wasn’t certain he should use Kirsht Buchshtav’s first name, Rimon, in the title. So he got in touch with her mother and sent her the song.

“Then there was a phone call and she said she played it for Rimon and they both loved it,” Brinn says. “That it brought them to tears and they both said they’d be honored to have her name on it. So that gave me the authority to actually release it and [on May 20] for the first time, I got a phone message from Rimon herself who’d been very much out of the public eye since she’d been released. She hasn’t made any public appearances or made any statements, but she sent me a message and said how much this song moved her. That brought me to tears. I feel like no matter what happens now I did something good. All these years of banging away on this guitar to no avail, to have some reason for it now.”