BINTEL BRIEFI’m losing my religion thanks to the war. Can Jewish tradition guide me?

Bintel says: Jewish tradition contains things you’ll love and things you might hate

Jewish wisdom contains both violent and pacifist ideas. Graphic by Mira Fox

A Bintel Brief, Yiddish for a bundle of letters, has been solving reader dilemmas since 1906. Send yours via email, social media or this form.

Dear Bintel,

Ever since the horrific events of Oct. 7, I have been so terribly confused. As a Jew, I was devastated by the loss and capture of so many innocent lives. I was terrified for my family in Israel.

But as Israel invaded Gaza, as its government rejected hostage deal after hostage deal, as months of brutal ground and air assaults took the lives of tens of thousands of Palestinians, I began to question what I thought my faith had taught me about the value of human life.

Because no matter how hard I try, I simply can’t blame everyday people in Gaza for the tragedy of Oct. 7. I can’t hold 2 million people responsible for the actions of the militants.

So I want to ask, in no uncertain terms: Does Judaism teach us that we have a responsibility to punish the many for the crimes of the few? Does it teach that the ends always justify the means? (And only when they are our ends — because we decry the phrase “by any means necessary” when applied to Palestinian freedom, and then turn and utter those same words to the end of bringing the hostages home?)

If it does, I’m not certain how I can put my faith in it any longer.

If it doesn’t, I’m left with the other question: Why do we not scream with every breath that is left to us against the bombs raining down on the refugees in Rafah?

The only answer I can see (and this scares me more than anything) is that our community does not see the value of Palestinian lives as equal to Jewish lives. If we don’t believe in an eye for an eye, if we don’t believe in revenge killing, if we don’t believe that the son should die for the crimes of the father, and yet we don’t do anything to stop the war in Gaza, does that mean we have accepted, in our hearts, that Palestinians aren’t people?

Signed,

Heartbroken for Humanity

Dear Heartbroken,

I can hear both pain and confusion in your writing — and you’re far from the only one.

Jews of all generations and backgrounds are struggling with how to feel about the war, about Israel and about their Jewish communities. Many of us have complex, tangled relationships to Israel, whether because of loved ones there or because of what we were taught growing up. Maybe it’s just because at some point, it seemed to become mandatory for Jews to have some sort of Big Feeling about Israel. And it’s all coming to a head in a very public way these days.

The first thing I’d say to you is that there’s not really one answer to what Jewish tradition says about war, or morality, or proportionate response. There’s not one answer to much of anything in Jewish tradition.

That’s what makes Judaism beautiful, in my opinion. But it can also be frustrating in a time like this.

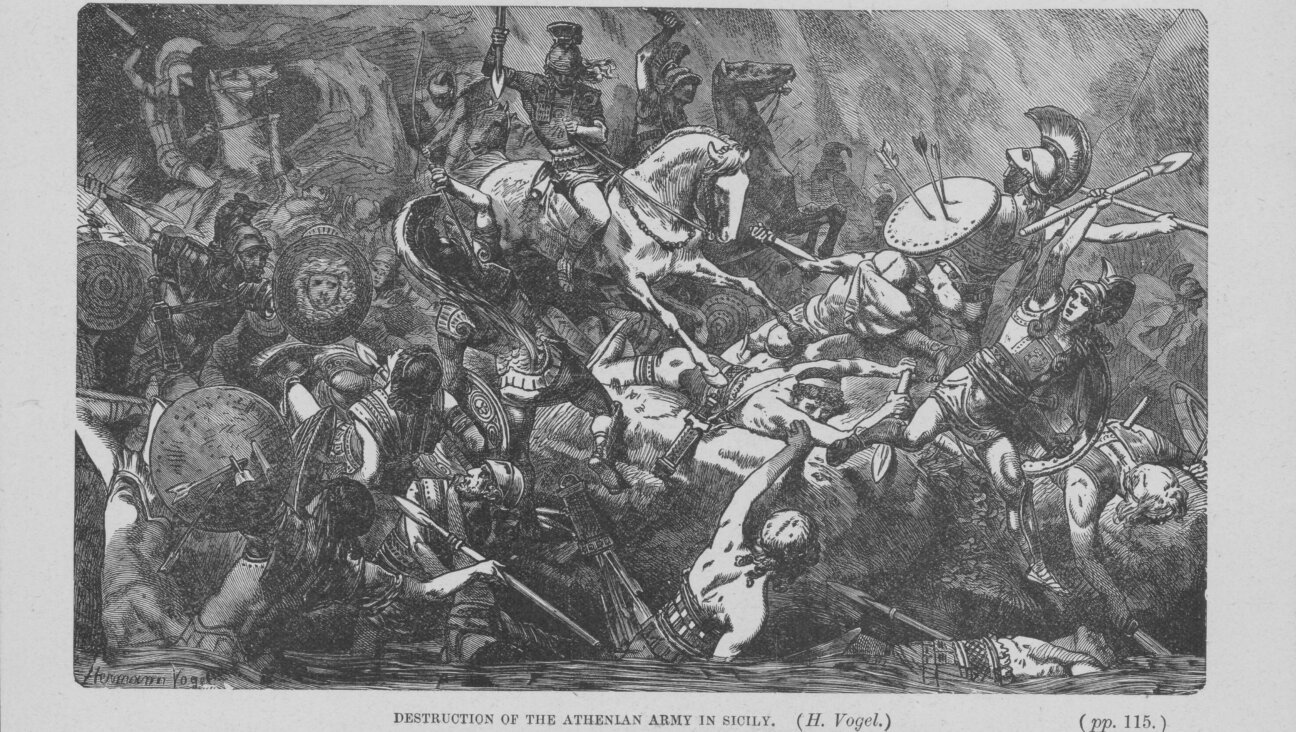

When you look at the Torah, there are passages commanding the total destruction of various enemy nations. After Amalek attacks the Israelites, God commands they all be killed; there’s no room for the idea of innocent Amalekite civilians. Indeed, the idea that Haman, the villain of the Purim story, is a descendent of Amalek is often cited as an example of why no Amalekite can be allowed to live. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has invoked Amalek in talking about the current war in Gaza.

On the other hand, Talmudic discussion and centuries of reinterpretation by revered rabbis have tempered these commands. And Judaism today is a rabbinic religion that relies on the writings of such sages codified in the Talmud and books of interpretation such as the mystical Book of Zohar, which sees Amalek as an allegory for evil, and the Shulchan Arukh — perhaps the most famous codex of Jewish law — which completely leaves out the command to destroy Amalek.

I’m not going to try to walk you through every Jewish text debating war or every text about ethics — it would be an entire college course, and then some. But you should do that work before you decide to throw out your religious identity.

Judaism contains multitudes; just because some people are using it to support something you stand against doesn’t mean you can’t use it to stand against them. There’s plenty of Jewish teachings that adamantly, vehemently emphasize the value of human life. Even some of the most seemingly black-and-white laws in Judaism — like not eating pork — can be overridden to save a life.

That still leaves your second question: Why aren’t more Jews speaking out against the suffering of civilians in Gaza?

First of all, many Jews are — there are Jews deeply involved in protest movements on campus, and Jewish groups such as IfNotNow, Jewish Voice for Peace and T’ruah that have been calling for a ceasefire. Rabbis and committed Jews of all denominations have written and preached about the need to end the war, condemned the civilian toll of Israel’s actions, and lobbied for more humanitarian aid to enter Gaza.

This might not be prominent in your community. So look around for other Jews whose views and actions align better with your own, and ways to ground your opposition to the violence within Jewish tradition.

Maybe that’s a Jewish antiwar movement, or maybe it’s a text-study group focused on learning more about what the rabbis have written about war and peace. Maybe it’s just having Shabbat dinners with like-minded people. If you live somewhere with few Jews, there are online options.

It may feel unsatisfying that my answer is, essentially, to do some research; it sounds like you feel that the situation is morally clear-cut and want a more definitive answer. But Judaism is a deeply human religion. The texts offer perspectives, unresolved debates, stories and examples, but ultimately leave it up to us, as a community and as individuals, to find our own answers. That gives us the flexibility to adapt while remaining grounded in our tradition, but it also leaves an uncomfortable amount of space for disagreement.

Think about the example I gave above — halakha, Jewish law, says we can break the rules of kashrut to save a life, but we’re the ones who have to determine whether the situation is, indeed, dire enough to require that. Your role, as a Jew in a time of war, is to learn enough about the text, the tradition and the current situation to advocate for the interpretations you find most compelling. And it’s that very debate that enriches us, as a community, and continually challenges us to do what’s right.

It’s a trite joke that wherever there are two Jews, there are three opinions, but it’s also a deep truth. The hard part is finding the Jews and opinions that resonate with you.

Beg to differ? Send your advice for Heartbroken for Humanity to [email protected], or submit a question of your own via our anonymous form.

Your turn

A recent advice-seeker wrote Bintel to say how disappointed she is that her non-Jewish friends don’t acknowledge Jewish holidays. Bintel suggested inviting them over for blintzes on Shavuot or a Hanukkah party.

One reader shared the frustration, and said she had even learned to say “Gung hay fat choy” — “wishing you prosperity” in Cantonese — to Asian friends for Lunar New Year and still never gets a Rosh Hashanah greeting in return. “If I can be aware of their holidays, why can’t they respond in kind?” she asked.

To which Bintel says: Only a nudnik could disagree with that.