She was a nice Jewish mother — and an organized-crime boss

Meet Fredericka Mandelbaum, who made a fortune from stolen goods and bank robberies

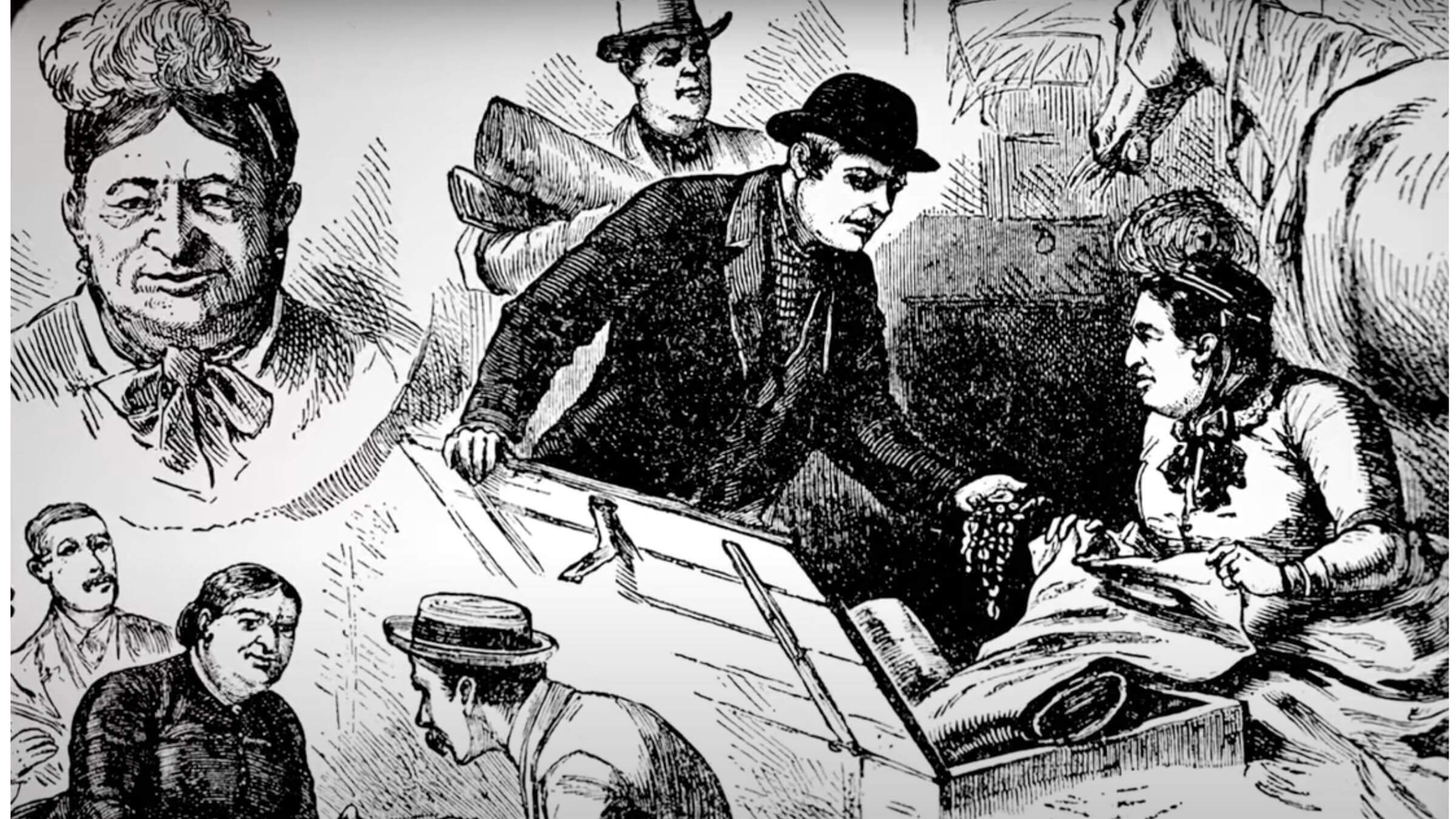

Detail from a montage depicting Mrs. Mandelbaum’s ill-gotten gains and the raid on her shop, from an 1884 issue of the National Police Gazette, a 19th- and early 20th-century scandal sheet. Courtesy of Van Every, “Sins of New York,” 1930

She was an adoring Jewish mother, a generous benefactor to her synagogue, Rodeph Sholom, and a proper 19th century lady who wore floor-length silk gowns.

But Fredericka Mandelbaum was also what her biographer, Margalit Fox, calls “America’s first major organized-crime boss.” She made a fortune selling stolen luxury goods — silk, lace, cashmere, jewels — and masterminded bank robberies carried out by her minions.

“How could the first major mob boss in America have been, not a big strapping guy with spats and a Tommy gun, but a nice, zaftig Jewish mother of four?” said Fox, a former New York Times obituary writer whose latest book, The Talented Mrs. Mandelbaum, published July 2. “It’s eye-poppingly strange and wonderful.”

Fox stumbled onto Mandelbaum’s story while looking for a new project after turning in the manuscript for her previous book, The Confidence Men, about British officers who scammed their way out of a World War I POW camp with a Ouija board.

She was looking in an encyclopedia of crime when it fell open to an entry about a school for aspiring thieves that had purportedly been run by Mandelbaum. Eventually Fox determined that the school story was an urban legend. But she found plenty of other material on Mandelbaum, including court records and hundreds of 19th century newspaper clippings. “Fredericka Mandelbaum was always there for the taking, but her life had to be put together like a mosaic,” Fox said.

A path to wealth from the Lower East Side

Mandelbaum was a German Jew who followed her husband Wolf to New York in 1850. They settled amid other poor immigrants in Kleindeutschland, a German enclave of the Lower East Side. Wolf worked as a peddler, as he had in the old country, while Fredericka started selling lace door to door.

But Fredericka “recognized quite early that that sort of low-paying wage work would never allow for the economic advancement that entrepreneurship could,” Fox said in an interview. “By the end of 1850, she was apprenticed to a couple of the big fences of the day, two Jewish men, and she learned to be a sharp-eyed judge of luxury fabrics — silk, cashmere, lace, seal skin — that passed through their hands.”

She began buying those goods from “young Oliver Twists” who pinched them from warehouses, wagons and ships unloading at waterfront docks. Then she resold them at a hefty profit. “The thief paid nothing for a bolt of silk because he’d stolen it,” Fox explained. “Mrs. Mandelbaum would pay the thief something like 10 to 25% of the wholesale price and then she’d turn around and charge the buyer — be it a housewife who sought her out furtively, or a tailor who needed raw materials — half to two-thirds of wholesale.”

Eventually, Fredericka bought a building at Clinton and Rivington streets and sold her ill-begotten goods from a modest ground-floor haberdashery while living upstairs in Versailles-like splendor.

“The few reporters that got to see it all remarked at the unlikeliness of having a dwelling like that in a milieu like the Lower East Side,” Fox said. “It was unheard of. She could have lived on Fifth Avenue, and she chose not to. She never forgot where she came from.”

A fortune in fabric

It’s a little hard to imagine, in today’s world of cheap fashion, just how precious fine fabrics were in Mandelbaum’s era. One example: A single cashmere shawl from that time would sell for the equivalent of $45,000 in today’s dollars.

“Remember how ubiquitous bolts of fabric had to be, because there was no ready-to-wear,” Fox explained. “Women’s shirtwaists were not available in shops until the end of the 19th century. Women’s dresses — this blew my mind — were not available to go into a store and buy until after World War I. So every woman, rich or poor, either had to make her own clothes or had them made.”

‘Marginalized three times over’: An immigrant, a woman, a Jew

Most women in Mandelbaum’s time who embarked on a life of crime were either shoplifters or prostitutes, and neither option suited her.

“Shoplifting was really penny ante stuff; you could never make a fortune doing that,” Fox said. “And for a proper married woman like Fredericka Mandelbaum, prostitution was beyond contemplation, so she really carved out a niche that few if any other women of her time did. There were plenty of other women in the criminal world, but I’m aware of few, if any, who rose so high and held that position in such a sustained way.”

Women haven’t been prominent in 20th century organized crime, either. “Think of the mob now and we think of the more recent generation of Italian men,” she said. “And in the earlier 20th century, there were lots of Jews who were running things. But even in that generation, which was a generation or two after her, women were gone from the upper ranks.”

It wasn’t just her smarts and ambition that drove Mandelbaum’s success, though: She was also in the right place at the right time. The country was shifting from an agrarian economy to one fueled by capitalism, and she built her fortune by skimming profits from legitimate commerce. At the same time, corruption had been normalized in New York by the political machine known as Tammany Hall.

“You greased every palm, from the cop on the beat all the way up to Boss Tweed,” Fox said, referring to the Tammany chief. “Mandelbaum saw that was the way business got done. For people like her, marginalized three times over — immigrant, woman, Jew — she wasn’t going to be able to do business like the Astors and the Vanderbilts on Fifth Avenue. But was there really that much difference between the way the upper-crust and the underworld did business? It’s just that one was legal and one wasn’t.”

So Mandelbaum became “a mogul of illegitimate capitalism,” turning the “disorganized crime” of violent hoodlums who had previously dominated the city’s underworld into “a lucrative, well-oiled business enterprise.”

The tide turns

Mandelbaum ran her operation with impunity for more than two decades. “Everyone knew what this woman was doing,” Fox said. “Yet strangely, the police were never able to arrest her. And of course, the reason was, she was wining and dining them.”

Eventually, though, the reformers had their day. Mandelbaum was cutting into the profits of bankers and business, and public sentiment was turning. A new district attorney went after her by deploying the Pinkertons, a private detective force. They entrapped her and then watched her house round-the-clock to make sure she didn’t get away before trial.

But she outsmarted them with a body double and hopped a train to Canada. When her case finally came to trial in December 1884 and the court clerk called her name, there was no answer.

Was her Jewishness ever mentioned in news coverage of her sensational misdeeds? Not much, Fox said, perhaps because it was assumed from her name that she was Jewish. However, a drawing of her from Puck magazine had what Fox describes as “a caricatured nose,” and a New York Times story about her downfall described her as a “gross” woman, and a “German Jewess” with “coarse masculine features.”

A dramatic return to New York

Mandelbaum sneaked back into town in 1885 when her beloved 18-year-old daughter Annie died of pneumonia. The body was laid out in the house at Clinton and Rivington and Mandelbaum was determined to kiss the girl one last time. She slipped into the building in disguise via the hidden entrances once used by thieves.

Someone suggested that Annie be buried in a Christian graveyard so that Mandelbaum could attend the funeral. “But Fredericka would not hear of it,” said Fox. “So Annie, at her mother’s insistence, was buried in accordance with her faith,” in the family plot in Rodeph Sholom’s Union Field Cemetery in Queens.

Fredericka did not attend the interment; she slipped back to Canada, and died there at age 68 in 1894. Her body was returned to New York; she’s buried in the same Jewish cemetery as her daughter.