Remembering Arnold Band, a towering figure in Jewish studies

Band, who has died at 94, brought a classicist touch to his studies of Agnon, Kafka, Yehoshua and countless others

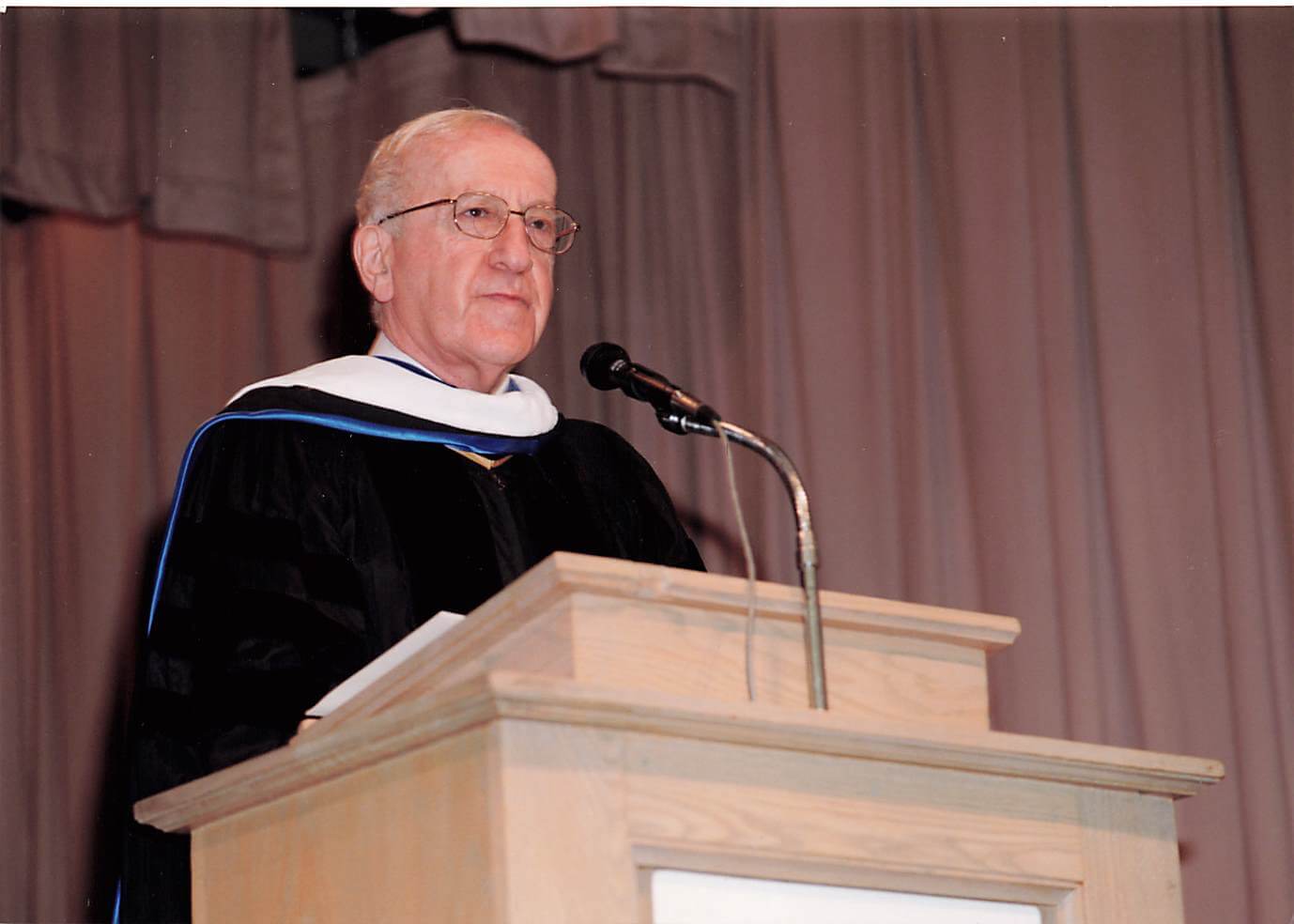

Arnold Band taught at UCLA for more than 50 years. Courtesy of Jonathan Band

Arnold J. Band, one of the great Hebrew literary scholars of the past 50 years and a towering figure in the global community of Jewish studies researchers, passed away Sunday, July 7, 2024, in Silver Spring, MD, at the age of 94. Arnie Band was a professor of Hebrew and comparative literature at UCLA for more than 50 years; together with Wolf Leslau and his fellow Bostonian Herbert Davidson, he arrived at UCLA in the 1950s and began to build a program in Jewish studies that is now one of the largest in the country. Beyond campus walls, Arnie, together with his wife, Ora, a renowned teacher of Hebrew, transformed their home in Beverly Hills into a salon for visiting Jewish studies dignitaries, local scholars in a wide array of fields, and other intellectuals and activists who treasured the warm hospitality and rich conversation of the Band home.

Arnold Band was born in Dorchester, MA in 1929, a bygone era in which that Boston neighborhood was a major center of Jewish life. His parents were immigrants from Eastern Europe, but the family home was not one in which Jewish learning or Hebrew language was readily imparted. For that, Arnie had to make his own way. He went five days a week to the Beth El Hebrew School in Dorchester, where one could emerge after six years of study, he noted in an autobiographical essay, with “a fair knowledge of Hebrew, still pronounced in the Ashkenazic dialect.” Band’s Hebrew learning continued at the high school Prozdor program of the Boston Hebrew College, whose teaching staff included first-rate scholars of Jewish studies who did not yet have an opportunity to receive university appointments.

What was unusual about Arnie Band’s education — or actually that of a cohort of young Jews in Boston — was that it proceeded along two parallel tracks. In the high school program at Hebrew College, Arnie, together with his friends and future scholars, Walter Ackerman and Isadore Twersky (who came from a very different background as scion of a Hasidic dynasty), immersed themselves in Jewish texts, history and literature. But this trio of young Jewish Bostonians also joined together on the path of secular studies. They attended the Boston Latin School, which afforded them and other children of immigrants (40% of whom were Jewish) a classical education that included Latin, Greek and French. From there, they moved on to Harvard College. Band, Ackerman, Twersky, together with Herbert Davidson, continued on for their doctorates at Harvard. While Twersky and Davidson worked under the tutelage of Harry Austryn Wolfson, who assumed the first chair in Jewish studies at a major U.S. university in 1925, Arnie Band took up graduate studies in classics and comparative literature, writing a dissertation on Aristophanes.

It is easy to forget this datum in his biography, because Band’s international reputation as a scholar was earned in the field of modern Hebrew and Jewish literature not classics. And yet, there always remained a classicist touch in his analysis of Hebrew literature. Arnie Band simply could not read a modern Hebrew text without paying heed to its ancient and medieval echoes. He understood well the claim of Gershom Scholem that an “apocalyptic thorn” was embedded in modern Hebrew language and literature, which, when pulled out, would unleash a torrent of unexpected traditionalist meanings. Band encountered Scholem during his year as a young visiting student at the Hebrew University in 1949-50, when he was first introduced to the stimulating and contentious intellectual ambience of Jerusalem.

It was in this world that Band would come to know the person whose writerly virtuosity would inspire his attention for the remainder of his career: Shmuel Yosef Agnon, the first and only Hebrew author to earn a Nobel Prize in Literature (1966). Agnon’s unparalleled command of Hebrew literature from the Bible to the modern revival, masterful wordplay, and devilish humor charmed and intrigued Arnie Band as a scholar. In fact, his most important monograph was Nostalgia and Nightmare (1968), a major study of Agnon that required organizing the author’s challenging and often changing literary corpus over more than a half century and organizing it according to the dual themes of a yearning for a lost past and a confrontation with the ravages of modernity.

Through his work on Agnon, Band became well-known in the scholarly firmament of Israel, admired by almost all (with the exception of a few characteristically sharp Jerusalem critics) and appreciated for his outstanding grasp of both written and (Boston-inflected) spoken Hebrew. Band wrote amply on Agnon and other major figures in Jewish literature including R. Nachman (of Breslov) M. Y. Berdichevsky, Ahad Ha-am, Chaim Nahman Bialik, Franz Kafka, and A. B. Yehoshua. His preferred form of scholarly writing was not the book, but rather the compact article or essay which allowed him the kind of measured control that he so valued. It was in his articles that one really encountered the genius of Arnie Band; his dazzling mastery of Jewish literature over the ages combined with the historian’s firm grasp of context and the theorist’s nuance in navigating among distinct and competing analytic approaches. Among the most treasured holdings in the Band literary vault are two wide-ranging volumes of his articles; one in English, Studies in Modern Jewish Literature, that was part of the Jewish Publication Society’s prestigious Scholars of Distinction series, and the second in Hebrew entitled She’elot nikhbadot.

Alongside his scholarly excellence, Arnie Band was an expert institution builder. He arrived at UCLA in 1959 and was hired to teach in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures not on the basis of his Harvard dissertation but rather on his deep knowledge in Hebrew literature. Over the course of a half century, Arnie was the most prominent figure in launching the university’s program in Jewish studies, teaching thousands of undergraduates and scores of graduate students, and hosting hundreds of visiting scholars and lecturers.

In 1994, he founded and served as the first director of the UCLA Center for Jewish Studies, a position that I inherited from him two years later. Band’s interests were not restricted to Jewish literature. He was also the moving force behind the creation of UCLA’s program (and later department) of comparative literature in 1969. In recognition of his contributions to UCLA, he was awarded the university’s distinguished teaching award in 1981 and was included among the institution’s most important personalities in 2019 on the occasion of its centennial. (It should also be noted that Band’s 1966 article in the American Jewish Year Book served as a catalyst to the creation of the Association for Jewish Studies, the leading learning society in the field.)

Notwithstanding all of his grand achievements as scholar and institutional player, Arnie Band was first and foremost a teacher. In this function, he conjoined the old-world rigor of the traditional melamed with the sophistication of a world-renowned literature professor. Hundreds of students had the unforgettable and terror-inducing experience of sitting in Arnie’s office reading Hebrew texts line by line, in which he let no error, minor as it might be, go uncorrected. For many future scholars at UCLA, Brandeis and Yale, Arnie’s tutorial was the singularly formative setting in which one learned how to read a text, attentive to its word choice, cadence, and form, as well as to the author’s biography and wider historical context. In my own case, the two classes I took with Arnie Band as an undergraduate at Yale in 1981-82 on modern Jewish and Hebrew literature so excited me as to consolidate my decision to go into the field of Jewish studies as a graduate student the next year.

A decade later, in 1991, I became Arnie’s colleague at UCLA. I didn’t know what to expect. Arnie could be intimidating, especially given his famously ornery demeanor. And yet, he taught me then and there one of the most valuable lessons I’ve learned over the course of my career; there is no greater thrill than seeing and encouraging a student to become a trusted colleague and friend. In Los Angeles, Arnie embraced me as an equal, and we spent decades dreaming, building up Jewish studies at UCLA, and even collaborating on a book project: the translation in English of Simon Rawidowicz’s long-lost essay from the early 1950s, “Ben `ever le-`arav” (Between Jew and Arab), in which he provocatively called for the repatriation of Palestinian refugees.

Rawidowicz’s Hebrew was exceptionally rich, idiosyncratic, and difficult — and the draft of the essay that survived was filled with mistakes. Over the course of several years, Arnie and I sat in his home study in Beverly Hills, parsing the manuscript, trying to divine Rawidowicz’s authorial intent, debating translation options, and finally producing a completed text in English. Although we had worked closely together for years, the time we spent on this project was an immense gift to me. I saw Arnie as he actually was beneath his forbidding exterior: an extraordinary font of erudition, an ever-present teacher, an equally willing partner and even student, a generous friend, and a person of great charm and constant humor. Arnie had a twinkle in his eye and a smile on his face as he challenged me with his complex Hebrew word play, an impulse he borrowed from his cherished literary hero, Agnon.

The room in which Arnie sat poring over texts with countless students was the atelier of a truly great scholar, teacher, and man — a monument to the power of words, language, and ideas. The world of Hebrew letters and Jewish culture was immensely enriched by the presence of Arnold Band, and now it is significantly diminished. May Arnie Band’s memory always be a blessing.