How a legendary Jewish sociologist’s faith in reason is what we need in this dangerous, fist-pumping time

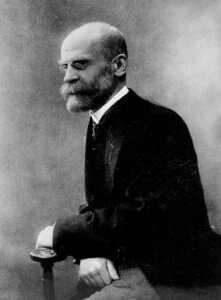

The son of.a French rabbi, Émile Durkheim understood the dangers of succumbing to our basest instincts

The former president makes a familiar gesture. Photo by Getty Images

150 years ago, a French-Jewish teenager told his father, a rabbi in the town of Épinal, that he had decided against entering rabbinical school, thus breaking with a family tradition that stretched back several generations. Yet this teen would never escape another family tradition where, he recalled, “the observance of the law was precept and example, and nothing intruded that might divert one from one’s duty.”

This young man, Émile Durkheim, went on to become one of the early 20th century’s most influential and original sociologists. Ranging from the forms of religious belief to the motives for suicide, Durkheim’s work in the late 19th century continues to influence of thinkers like Jonathan Haidt in the early 21st century. In fact, the French thinker’s insights on morality and politics have an especially tragic relevance for the eruption of violent events in our time.

Durkheim was no stranger to political violence and division. He stood fast during the Dreyfus Affair, when fin-de-siècle France was nearly torn in two by the fierce riptide of antisemitism. Not only did Durkheim champion the French Jewish officer wrongly convicted of treason, but he was also a founding father of the Ligue des droits de l’homme (League of Human Rights), which continues to play a crucial role in the defense of immigrants and refugees. Less well known but equally important, he persuaded his university classmate, the great Socialist leader Jean Jaurès, to rally the political left to the cause of Dreyfus.

Deeply private and apolitical, Durkheim nevertheless strode into the political arena. Given his unwavering faith in human reason, his unswerving attachment to scientific fact, and his unbending love of republican ideals, how could he do otherwise? “Once one has established the existence of an evil, what it consists of and on what it depends, when one knows in consequence the general characteristics of the remedy,” Durkheim affirmed, “the essential thing is not to draw up in advance a plan which foresees everything; it is to get resolutely to work.”

It does not take a doctorate in sociology to identify the many evils that confront us at this moment in our history. First, the effort to kill another human being — in this case, a once and perhaps future president — manifests an evil specific to the aspiring assassin. Second, that someone with murderous intent can buy an assault rifle as easily as others buy a kitchen appliance reflects a deep structural evil specific to our nation. Third, evil happens when leaders exhort their followers, whether for selfish or selfless reasons, to defy the rule of law and defile the civilized norms of society.

It does take a Durkheim, however, to insist upon the role that politics must play to serve as a rampart against such instances of evil. Like his contemporary Max Weber, Durkheim feared the froid moral, or moral chilling that accompanies the relentless process of modernization. It leads to a state of anomie, Durkheim’s famous coinage for the state of confusion and alienation that results from the fraying of the social traditions that once bound us together. When he announced that “the former gods are growing old or dying, and other have yet to be born,” he was warning us against the an individualism that runs riot and a morality runs in circles, unable to find a commonly agreed center.

Unlike Weber, Durkheim held fast to the primacy of reason in human affairs. As a student of religious practices, he had no illusions about the powerful pull of unreason in our lives. What more tragic reminder of this than World War I, the man-made cataclysm which took the life of his son André in 1915. At the same time, Durkheim was deeply attached to what he called the cult of the human person. This misleading phrase does not mean devotion to, say, my personal desires and demands, but instead to my ideal self that has been shaped by a society devoted to the cultivation of reason and the care for others.

This helps to explain the vital, nearly sacred role assigned to grade and high school teachers in republican France. The task of these men and women, Durkheim declared, was to teach “those principles which in spite of all divergences are from this time on the basis of our civilization, implicitly or explicitly common to all, and which few would dare to deny: the respect for reason, for science, for the ideas and sentiments which are the basis of our democratic morality.”

Of course, this was in a different time and a different country. As a result, Durkheim’s conviction that faith in reason and science could replace faith in older forms or gods, now seems perfectly quaint in an age of where the denial of climate change, electoral results, and even a shared reality has become commonplace.

But it would be tragically wrong to surrender Durkheim’s faith in reason, especially when the consequences of abandoning it are too great to contemplate. Consider the example set by his friend Jaurès, who was assassinated by a nationalist fanatic on the eve of the war he had striven to avert. His republican reflex was not one to appeal, with a fist pounding the air, to our base instincts. Instead, he moved millions by appealing to what is best in us. As he declared, in words that echo Durkheim’s own conviction, “Courage is looking for and telling the truth, not living by the law of the triumphant lie.”