A masterful new Kafka book will bring you closer to the writer than ever before

Mark Harman’s new translation of Kafka’s stories may just be the best book published this year

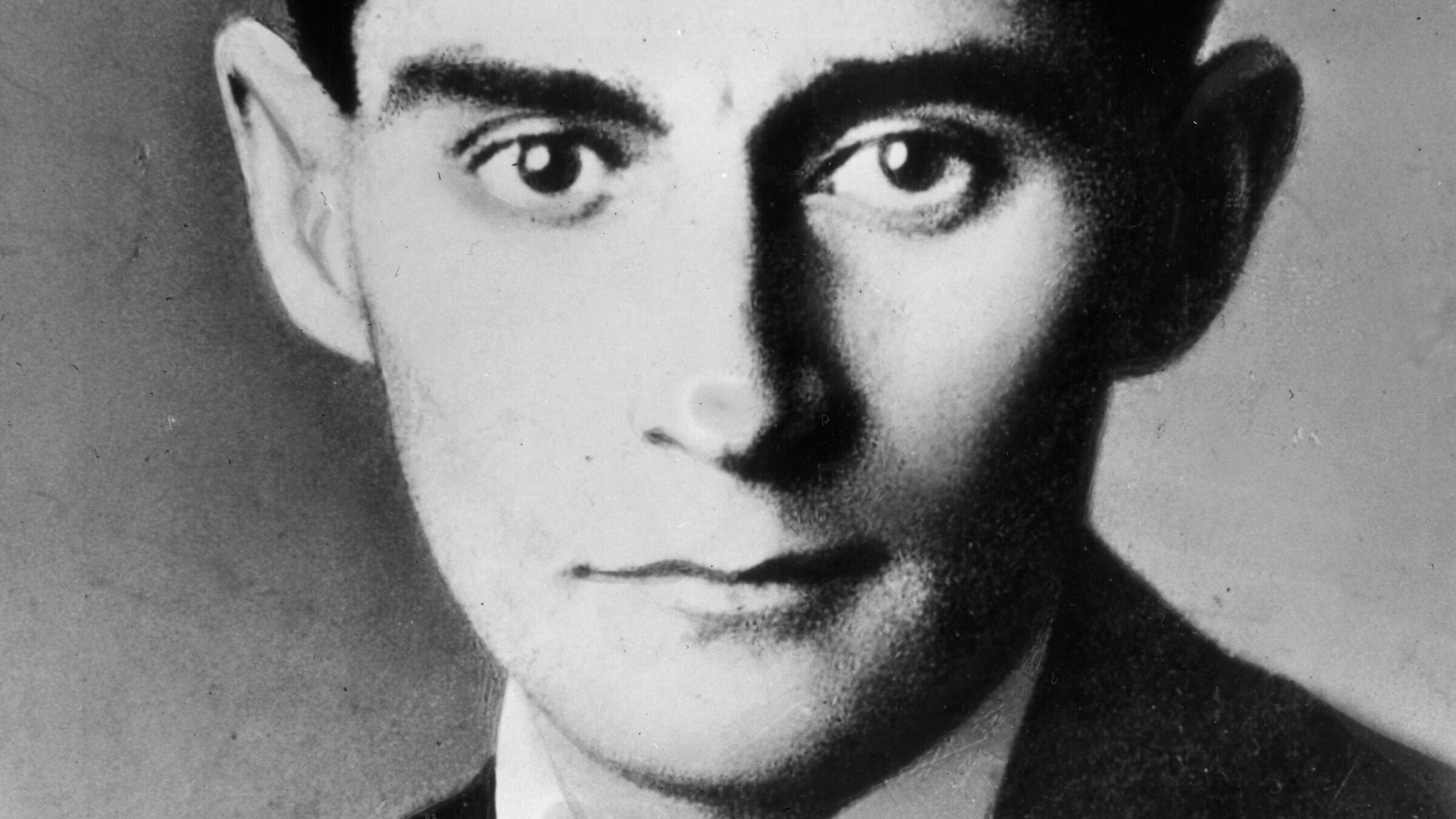

A portrait of Franz Kafka. Photo by Getty Images

Selected Stories

By Franz Kafka, translated by Mark Harman

Harvard University Press., 304 pages, $28

Franz Kafka was not a household name during his lifetime, but he was admired by the kinds of readers who could recognize greatness and immediately usher it into their house of reading — Rainer Maria Rilke and Thomas Mann. The Nazis banned Kafka’s books, yet that didn’t stop the great poet W.H. Auden from reading him and writing, in 1941, as the Nazis were doing their utmost to exterminate Jews and Jewish culture, that Kafka “was the artist who comes nearest to bearing the same kind of relation to our age that Dante, Shakespeare, and Goethe bore to theirs.”

I admit I was skeptical about what turned out to be the best book I have read this year. When I first heard about this new translation of Kafka’s stories, I wondered whether it was even necessary. Good translations into English exist, dating back to the influential postwar efforts of Willa and Edwin Muir, who introduced Kafka to English-language readers; there is also plenty of intriguing biographical information available, such as the lauded recent biography of Kafka by Reiner Stach, translated into English by Shelley Frisch. But it’s clear that there is far more to say, and that it’s a pleasure to learn how Gabriel Garcia Márquez reacted to reading Kafka, along with his effect on Auden, Rilke and Mann.

From its very first sentence, Kafka: Selected Stories, edited and translated by Mark Harman, dispelled all my doubts. Harman’s translation moved moved me deep into Kafka’s world, bringing to life Kafka’s friends, girlfriends, parents, sisters, and most of all, his concerns as a writer and as a Jew in a way no other book I have ever read has.

At every turn, and whenever possible, Harman — a professor emeritus of German and English at Elizabethtown College — brings the reader super-close to Kafka’s original German with notes that explain what might seem like minor moments in translation that are in fact essential in the German. And it must be said that Harman’s translation is not like other translations; for starters, Harman re-titles “The Metamorphosis,” “The Transformation,” and explains why. He traces how Kafka transformed himself to focus entirely on writing, creating “the compelling yet also stylized autobiographical persona that Kafka creates in his diaries and letters.”

Harman also tries hard to preserve what he describes as “Kafka’s shifting choices when it comes to punctuation,” which can lead to surprises for readers familiar with other translations. Through it all, Harman tries hard to stay very close to the German. He writes that he resisted the urge to “make the English more vivid, expressive, and colorful than Kafka’s plain and understated German.”

I guarantee that even if you have read a ton about Kafka, this 60-page introduction will reveal something about Kafka you never knew before.

“While working on this project, I kept discovering new things about Kafka that I had missed in four decades reading, teaching, and writing about his work,” Harman writes. “My hope is that readers of this book will also make their own discoveries.”

Among other tidbits, I learned that Kafka’s grandfather was a shochet, or ritual slaughterer; what Kafka’s writing desk likely looked like, that Kafka’s father forced his mother to work long hours in their store, and that his mother blamed the deaths of two of her sons in infancy on those interminable hours. Harman suggests that the roots of Kafka’s loneliness came from the mere fact that his parents worked all the time.

And there are plenty of fascinating and new-to-me details about Kafka’s high-stress, high-caliber education, which his parents very much wanted him to acquire, and which they themselves did not have. Some of the biggest surprises here come from quotes from people who knew Kafka. For example, I was deeply moved by this passage from the obituary that same Jesenská — his only non-Jewish girlfriend — wrote for Kafka:

“He understood people as only someone of great and nervous sensitivity can, someone who is alone, someone who can recognize others in a flash, almost like a prophet.”

It’s a beautiful sentence, and I couldn’t resist thinking about how so many Jewish writers seem to be fascinated by prophecy or described by others as prophets of sorts. Isaac Bashevis Singer, in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, said: “In the history of old Jewish literature there was never any basic difference between the poet and the prophet. Our ancient poetry often became law and a way of life.”

Harman seems to have read and watched everything related to Kafka, including the Shoah Foundation’s interview with Kafka’s niece. In that interview, she mentions Kafka’s three sisters’ amazement when they received posthumous royalties for their brother’s work. Only then did they realize he was a “real writer,” shortly before all three were murdered at a concentration camp.

Throughout this book, Harman also annotates everything worth annotating, so that the reader can get as close to the German as possible. One of his strengths is explaining when and why it is “difficult to interpret exactly what is meant,” which reminded me of what some Torah commentators sometimes say about thorny passages in the Torah; the great Rashi, famously occasionally comments eineni yodea, or “I don’t know.” *

Another pleasure of this book is how Harman traces Kafka’s increasing interest in Judaism as well as his ambivalence — “what do I have in common with Jews? I hardly have anything in common with myself, and should stand very quietly in a corner, content that I can breathe,” Kafka writes.

Harman details Kafka’s interest in Hebrew, as well as his interest in Hasidic rabbis, as evidenced by his encounter with the Belzer Rebbe, leader of the Belz Hasidic sect, at a spa in 1916. The photo of the Hasidim at the spa is one of the treasures of this book.

Then there is the role of friendship in Kafka’s exploration of Jewish identity. Harman writes of how Kafka befriended an actor in the Yiddish theater, Yitzhak Löwy, who had a deep influence on Kafka; so, too, did Georg Mordechai Langer, who grew up in an assimilated family, became a Hasid, and then returned to secular life in the big city but did not give up some of his Hasidic garb, to the horror of his family.

Harman relates that “the character in “The Judgment” known only as the “friend in Russia,” may be partly modeled on Löwy, who grew up in Warsaw while it was still under Russian rule and whose life as a nomadic actor became increasingly precarious.

Harman also explores Kafka’s relationships with women. “Although the relationship with Milena was short-lived, it nonetheless affected him deeply as a person, a writer, and a Jew,” Harman writes. “During the affair with Milena, his only serious relationship with a non-Jewish woman, Kafka began to see himself as the ‘most Western-Jewish’ of European Jews, a notion which covertly underlies his third and final novel, The Castle.”

The truth is that everything in this book is worth reading — the translator’s introduction; the actual introduction; the titles of the stories; the actual stories in translation; even the notes in the back of the book, which are a veritable treasure trove. From the notes, I learned that Auden’s 1941 essay in The New Republic, in which he praised Kafka as being in the same league as Dante and Shakespeare, was, amazingly enough, titled “The Wandering Jew.”

But I would be remiss if I did not mention that another important contribution Harman’s book offers is a window into history. It’s easy to forget that 50 million people died globally in the influenza epidemic of 1918-1920, according to one estimate; Harman slips this in as he mentions that Kafka managed to survive it. As we consider how the coronavirus pandemic, inflation, and ongoing wars are contributing to global political instability, those small historical details of the years of Kafka’s life add contemporary resonance — and of course, fear and foreboding — to the reading experience. It’s just another way Harman brings us into Kafka’s inner world.