How James Earl Jones became a true friend of Jewish artists and the Jewish people

The legendary actor worked with such luminaries as Stanley Kubrick and Joe Papp

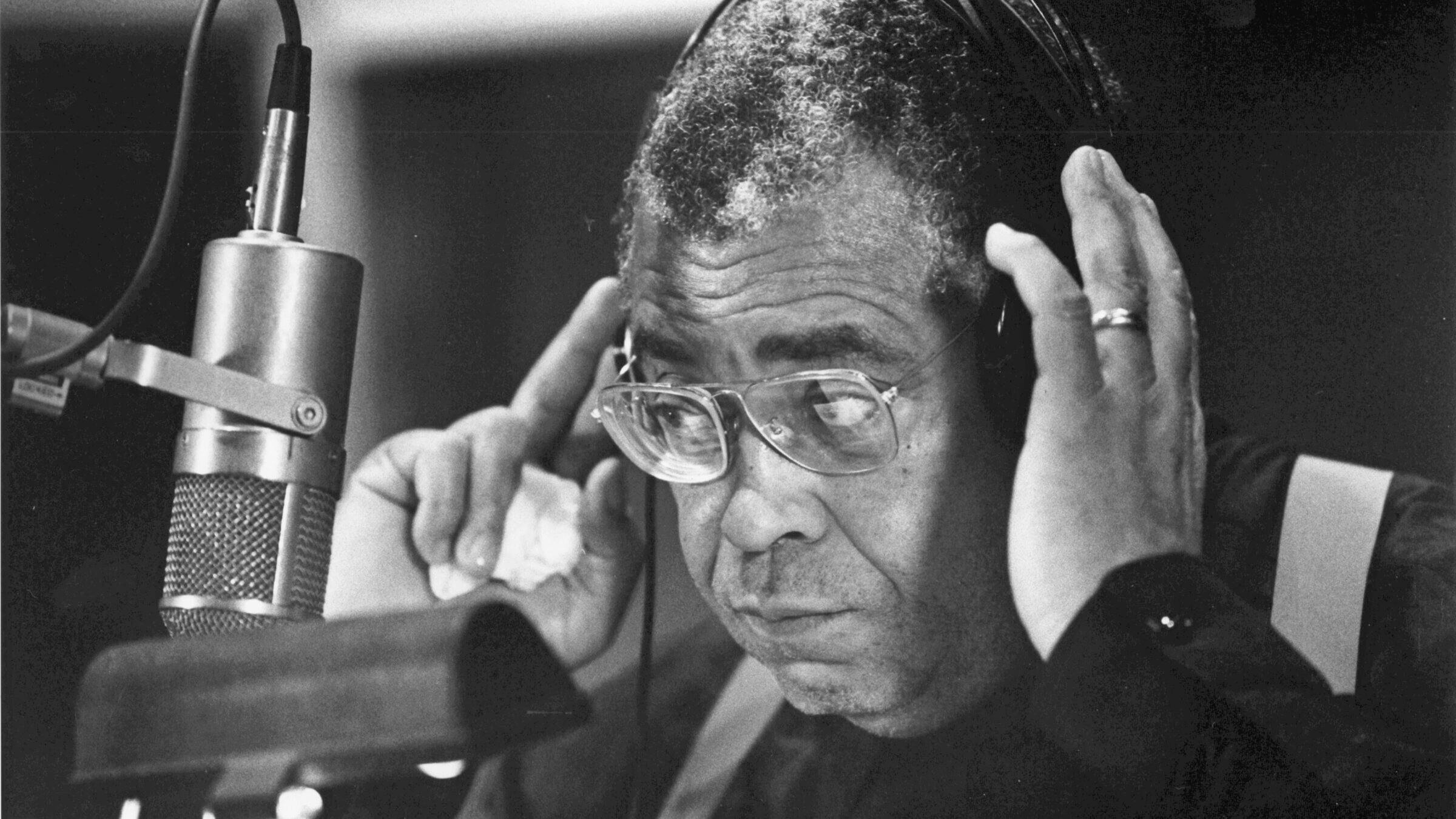

James Earl Jones adjusting his headphones, 1991. Photo by Getty Images

James Earl Jones, the actor celebrated as the voice of Darth Vader who died Sept. 9 at the age of 93, modestly claimed to be merely “special effects” for the Star Wars films; in a similar way, Jewish history and culture might be said to be part of the special effects of his storied career from its very beginnings.

Forty years ago at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, Jones participated in a Days of remembrance 1984 event organized by the United States Holocaust Memorial Council, alongside other speakers such as Elie Wiesel and actors Joseph Wiseman and Lorne Greene.

With empathy and familiarity, Jones narrated introductions to Zog nit keyn mol (Partisan Song), a Yiddish anthem of Holocaust survivors with lyrics written in the Vilna Ghetto by Hirsh Glick.

As part of the program, Jones also introduced segments on such texts as “A Journal of the Warsaw Ghetto” by Chaim Aron Kaplan, a Hebrew scholar who was murdered at Treblinka in 1942, as well as another text on the Łódź Ghetto.

James Earl Jones was no stranger to such charitable endeavors, or to modern Jewish history. In 2001, he and Mandy Patinkin co-chaired a fundraising dinner for Tzivos Hashem, a youth group of the Chabad movement, partnered by the Joseph Papp Children’s Humanitarian Fund.

On less public occasions, Jones could also display Yiddishkeit, as the comic actor Leslie Jordan noted in his autobiography about a Passover seder in California, hosted by the uncle of Jordan’s manager. Jones was asked to narrate the karpas ritual about dipping vegetables in salty water to remind guests of the tears shed by Jews during their slavery in Egypt.

“I looked around the Passover table and everyone was misty eyed. I got choked up and I’m not even Jewish,” Jordan wrote. “James Earl Jones, reading ancient, sacred words from the Torah.”

Although karpas in mentioned in The Book of Esther and commentary by Rashi and not in the Torah, the sonorous voice of Jones was so persuasive that listeners might believe its authenticity extended anywhere in Yiddishkeit.

Small wonder that around 1951, when Jones was toiling as a janitor and stage carpenter to subsidize his nascent career as a young actor, the Jewish writer Howard Fast enlisted him to recite a prose poem. The work by Fast unified Jewish and black culture, and was read by Jones at a concert of the Jewish Studies division of the Jefferson School of Social Science in New York.

One year earlier, according to Fast’s biographer Gerald Sorin, Jones was hired to act in a production of Fast’s play The Hammer, about the struggles of an American Jewish family during the Second World War.

As Fast recounted the story later, the Jewish parents entered onstage, portrayed by diminutive Jewish actors. Then their son appeared, the strapping James Earl Jones, with a “bass voice that shook the walls of the little theater.”

Before long, Jones was on Broadway as Edward the butler in the 1958 play Sunrise at Campobello by Isadore “Dore” Schary. In 1963 he was cast in East Side West Side, a TV series created by David Susskind and two years later, he appeared in a daytime drama, As the World Turns, created by Irna Phillips, the Chicago Jewish doyenne of soap opera.

Jones was soon starring in Shakespeare in the Park productions by Joe Papp (born Papirofsky) but his real breakthrough was 1968’s The Great White Hope by Brooklyn Jewish playwright Howard Sackler, a drama inspired by the troubled life of the champion boxer Jack Johnson.

Sackler, whose ear for dramatic dialogue was honed by directing over 200 recordings for Caedmon Audio featuring legendary English thespians, must have kvelled at the already renowned vocal prowess of Jones.

By then, Jones had already made his film debut as a bombardier in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove after Kubrick had attended a Joe Papp production of The Merchant of Venice to see another actor, but was reportedly impressed by Jones’ performance in a supporting role.

Jones’ early film career went on to feature a portrait of an African American family, Claudine (1974), produced by the Jewish leftist Hannah Weinstein and directed by John Berry (born Jak Szold of Polish and Romanian Jewish origin). As detailed by film historian Wil Haygood, the seriocomic, empathetic portrayal of the characters entrusted to Jones and other actors in Claudine were carefully honed by the Jewish creators of the movie.

Such was the powerful allure of Jones’ vocal effects, personality, and dramatic talent that he was cited even in a Jewish ritual context.

A book on ancestry by David Hertzel includes an interview with an adherent of Mormonism who recounts how he attended services a few times in a Utah synagogue where the chazzan was an “African American guy with a voice like James Earl Jones.”

The effect of the Jones soundalike chanting “in Hebrew these incredibly beautiful, powerful Psalms” inspired total acceptance from the congregation: “This person is of Israel, he’s been adopted in.”

By the early 70s, Jones was likewise adopted for roles with some ancillary Jewish resonance. An early version of the film Blazing Saddles by Jewish screenwriter Andrew Bergman planned to feature Jones in the lead role of the sheriff, before Mel Brooks became involved and the project was revised.

Another rare missed opportunity for Jones was a 1981 BBC-TV film of Shakespeare’s Othello where the English Jewish director Jonathan Miller failed to protest when the British actor’s union insisted that all roles in the Shakespeare series should be reserved for Brits.

According to his biographer, Miller dismissed Jones without an argument on the grounds that he would have been the only actor in the cast with an American accent. Instead, the title role was performed by Anthony Hopkins in blackface.

Such mishaps were rare in a career that was mostly triumphant, from revivals of the American Jewish author Alfred Uhry’s Driving Miss Daisy to George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s You Can’t Take It with You.

The geniality and impression of being a true mensch radiated in all his appearances, as recounted in a 2009 account by Steven Keslowitz of the lives of his grandparents as Holocaust survivors. Keslowitz notes that when bubbe and zayde once happened upon Jones unexpectedly in a Prague Jewish cemetery, he took the time to chat with them, warmly taking an interest in their experience with quintessential haimish attentiveness.

This humanity intertwined with affectionate involvement with Judaism throughout his long trajectory as an actor made James Earl Jones a true friend of the Jewish people. His memory is already a blessing.