Is it really so wrong to be into Nazi kink?

A new book mixes memoir and theory to consider what’s tangled up in Holocaust sex scenes, and Jewish identity at large

A few covers from Nazisploitation films and stalag fiction. Graphic by Canva

Kink is less taboo than ever today. Phrases like “don’t yuck somebody’s yum” are part of everyday parlance. 50 Shades of Grey was a huge hit as both book and movie. Feeld, a kinky dating app, just started a glossy print magazine; The New York Times covered the launch party, where the city’s youngest and hottest literati rubbed shoulders with, uh, Woody Allen.

Yet for all the mainstreaming of bondage or spanking, some desires remain taboo. Perhaps top amongst those is Nazi kink. Roleplaying and BDSM may be nothing to be ashamed of, but when an SS uniform is added to the mix, that seems to cross a line.

Leora Fridman encountered this phenomenon while talking to a therapist friend. The friend theorizes that BDSM is a way to process trauma through reenacting it, and opines that “all coping mechanisms are legitimate.” Well, all except one, apparently.

When Fridman mentions that she’d been watching some Nazi porn, and was curious about the genre, the friend gets upset. “I just don’t know why you would go there,” she says. “I wish you didn’t feel you had to do this.”

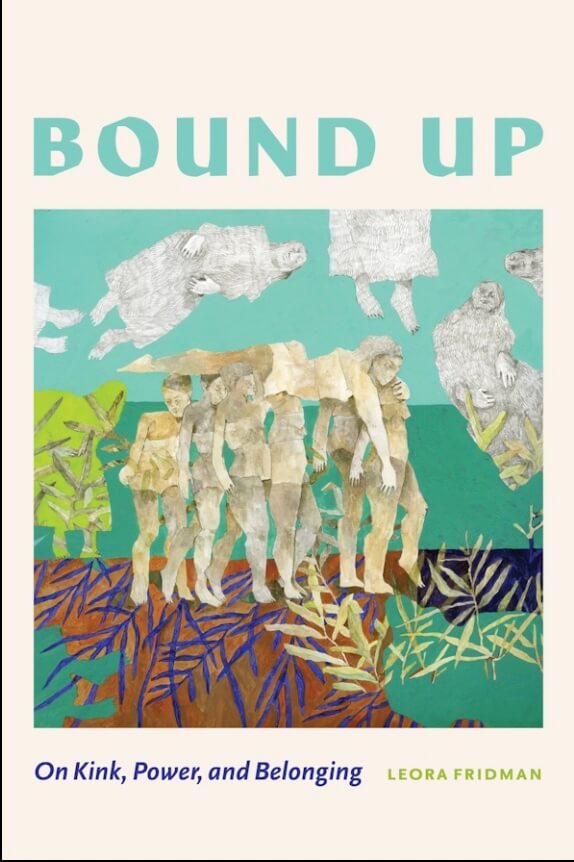

Fridman writes about the conversation in Bound Up: On Kink, Power and Belonging, a work that weaves together Fridman’s own experiences of desire with political theory and historical research. It’s the product of years of digging into strange corners of the internet, sure, but it was prompted less by Nazi porn than by the questions evoked by living as a Jew in Berlin, and a white woman in the U.S. In Germany, she was constantly viewed through the lens of her Jewishness; while engaged in activism for racial justice in the U.S., she was seen as a white woman.

Early in the book, Fridman recalls a date in Berlin with a German she met as a teen in a Jewish summer program. He’s drawn to her, and to Jewishness, perhaps out of a sense of cultural guilt. She’s drawn to him because she’s so aware of their differences; she calls him “her Aryan.” This attraction sparks her interest in Nazi kink.

But the rest of the book is digressive, often leaving the kink behind to wander into a memory of being a Jewish teenage girl with too-curly hair or thoughts about the symbolism of the “diaspora garden” at a Jewish museum. But for Fridman, these thoughts are all part of the same question about what it means to be Jewish today.

For her, the most interesting, most immediate way to work through these themes of identity, oppression, body and history is through sex. When we spoke on Zoom, she was careful to emphasize that her exploration of these questions through Nazi kink, or through sex at all, is her own journey, not necessarily one she’s recommending to others. Still, for her, kink provides an intersection of the physical and the emotional, and of transgression and play, that makes for fertile ground for exploration.

“For me it feels very much connected to the question throughout the book of what happens when generations upon generations of Jews are obsessed with their own victimhood,” Fridman told me. “What does it do to our understanding of our own bodies?”

Nazi kink through the ages

None of this is, exactly, new. As Fridman details, Nazi kink has been around for only a few years less than the Holocaust. In the early days of Israel’s statehood, survivors wrote erotica called stalag fiction, purporting to be true stories of male prisoners being abused by female guards in the camps; at the end, the prisoner almost always overpowers and rapes his busty blonde tormentor.

On one hand, these tales reinforced the nascent idea of the “new Jew,” the Israeli sabra, no longer a victim but instead able to overpower their oppressors. But the erotica was also educational; in the immediate aftermath of World War II, when survivors barely talked about the camps, these books, with titles such as I Was Colonel Schultz’s Private Bitch, were one of the only ways people processed, or even learned about, what happened.

Then there’s a whole genre of Nazi exploitation films, perhaps most famously Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS, which was widely criticized but nevertheless a financial success. Disgust, Fridman points out, requires fascination as well.

But at a certain point, however, these kinds of movies seem to have stopped; the Holocaust became too sacred.

Nazi kink subcultures still exist online, however, if you look hard enough. The intensity of their transgressiveness, however, is evident in how difficult they are to find; major sites like Pornhub won’t even let you use search terms like “Nazi” or “concentration camp” or “Jew,” even though they have entire categories for other controversial fantasies such as, say, having sex with your step-sibling.

Instead, Fridman finds strange and fascinating crossovers between fetish communities. In the furry community — a sometimes-sexual subculture where people identify, and dress, as animals — one man, who identifies as a wolf, also wears an S.S. armband, and the erotica includes, somehow, Aryan forest critters.

Perhaps it’s only in the alternate reality of furry culture that there’s enough distance between reality and fantasy that Nazi kink seems, at least partially, allowed.

The politics of kink

It’s obvious why people are uncomfortable with the idea that anything about the Holocaust might appeal or attract. Even if it’s roleplay, heavily staged and kept at a dramatic distance, it brings Nazis into a deeply intimate space. Even if the Nazi in question is a wolf.

But that sort of complaint can also be applied to just about any kind of BDSM play; isn’t it just as problematic that people are attracted to imagery of abuse and violence, even if it’s not real? Is Nazi kink really so different from any other form of sexual play with power and domination?

Indeed, plenty of people complain that all of these genres of kink are dangerous. Some researchers worry that the imagery of BDSM, no matter how consensual and carefully controlled with safe words and boundaries, normalizes and eroticizes violence or incest. Adult websites often use racial stereotypes in their categories, or only employ non-white performers in scenes that reinforce social stigmas. Fantasies, however divorced from reality, don’t exist in a vacuum.

These other concerns, however, have been grappled with so much more, and more openly, than Nazi kink. Slave Play, a controversial work by Jeremy O. Harris about interracial couples bringing plantation slavery into their sexual life, even made Broadway. Critics lauded it, and seemed able to consider its delicate questions of how sex can be a venue for working through history, trauma and identity — the back half of the play takes place in a sex therapist’s office as the couples work through what emotions and desires the plantation sex scene brought up, and how the kink accessed deeper needs.

Of course, Slave Play is a play, not an actual porn scene and, in its later acts, it leaves the sex behind to discuss what it means. None of the actors need answer for their transgressive desires since those desires are not actually their own, nor performed for the benefit of the audience’s sexual gratification.

Fridman grapples with this near the end of Bound Up, exploring the idea that “role-play is not exclusively imaginary, but meaningful because it takes place inside reproduced racial and gender norms.” She references the research of anthropologist Margo Weiss, who wrote that bondage performance is “erotically and politically powerful” because social forces remain in tension within the imagined scene.

It’s these social forces that draw Fridman to Nazi kink. When we spoke, she said that, in a way, victimhood is in fact a comfortable identity; imagining herself as an Anne Frank figure hiding in the attic is familiar.

“In my reunderstanding of Jewish victimhood narratives in this book, I feel this kind of solipsism. We’re in the attic, we’re always going to be in the attic,” she told me. “I’m not actually in the attic. What do I need psychologically to get out of the attic?”

But even after a whole book of wondering about Nazi kink, Fridman still doesn’t quite have an answer to whether it holds the key to resolving her identity. Perhaps that’s because, as she told me, she still hasn’t really found anyone who wants to play the Nazi.