Paintings of unbearable life in the Lodz Ghetto

An exhibit in Warsaw displays artwork created by Jews as a strategy for staying alive.

“The Fecalists / Feces Disposal”, painted by the prisoner Jozef Kowner, 1944 Courtesy of the Jewish Historical Institute

All images in this article are from the Collection of the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland in the deposit E. Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw

An exhibition of art from the Lodz ghetto might sound like a paradox. How could Jews have made art in the hellish conditions of a World War II ghetto?

“Capturing the Ghetto: Artistic Portrayals of Everyday Life in the Lodz Ghetto,” on view at the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, allows visitors to understand that making art in the Lodz ghetto was a strategy for staying alive. It also helped artists cling to a sense of humanity in desperately difficult conditions.

Before the war, Lodz had the second largest Jewish population in Poland, after Warsaw. Many Jews worked in its numerous textile factories. The city had a vibrant Yiddish cultural life, and many of its residents were writers, journalists and artists.

In early 1940, the Nazis created the Lodz ghetto, and 160,000 Jews were forced to move there before it was closed off with barbed wire on April 30. By the time the ghetto was liquidated in summer 1944, more than 200,000 Jews had been interned there. They endured starvation and disease, made worse by overcrowding and poor sanitation. Around 45,000 died. Most who were still alive in 1944 were deported to Chelmno or Auschwitz and murdered.

The Lodz ghetto was administered by the controversial “Elder of the Jews,” Chaim Rumkowski. (Day-to-day life in the ghettos was typically run by Jews appointed by the Nazis.) Rumkowski’s mantra for Lodz was: “Our only path is work.” If Jewish prisoners did useful work and made themselves indispensable to the Nazis, they might survive. He organized an elaborate system of departments and workshops, devoted to all kinds of small-scale manufacturing.

Under harsh conditions, prisoners turned out shoes, clothing, carpets, wood and metal objects, paper products and more — mainly for use by the Nazis. Several of these handmade items are included in the exhibition. Some items are inscribed with the names of Nazi officials. Decorative objects like cigar cases were also made by prisoners as gifts for Rumkowski and his inner circle. Since Rumkowski controlled food distribution in the ghetto, the prisoners apparently hoped to receive a little more food in exchange for the gifts.

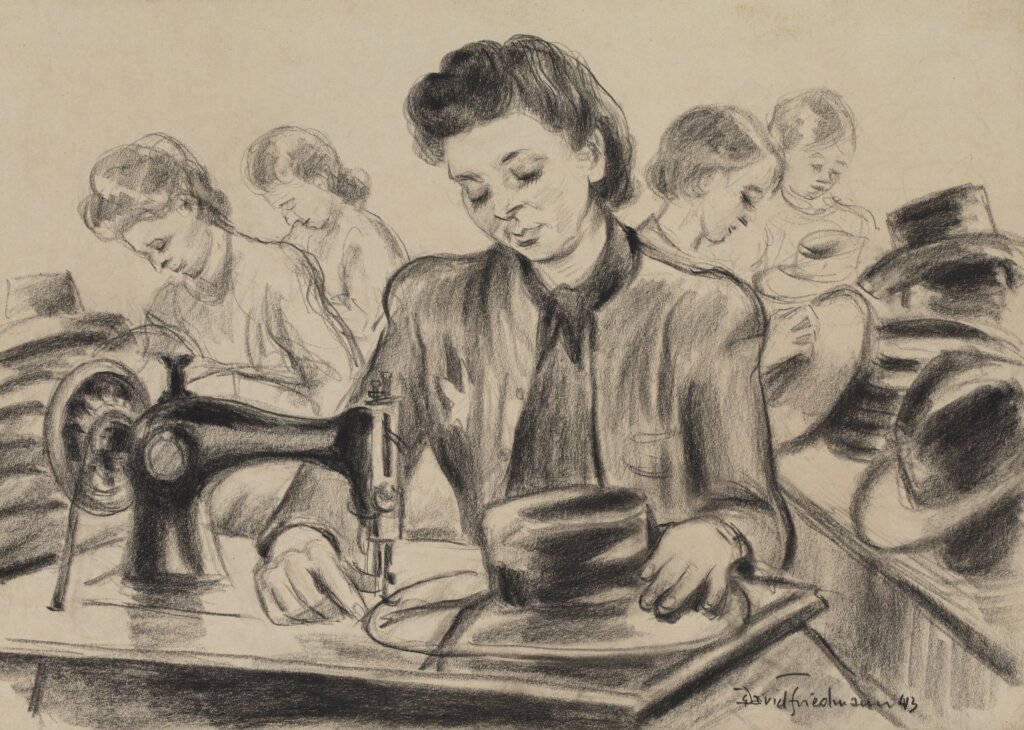

Dozens of highly trained professional artists were interned in the ghetto, and used their skills in many different departments. Rumkowski sometimes commissioned art to show his Nazi bosses how hard Jews were working and how productive they were. A remarkable example was discovered in storage only a few years ago at Warsaw’s Jewish Historical Institute where the exhibit takes place. It’s by David Friedmann, a successful artist before and after the war (he survived deportation to Auschwitz). His portfolio documents a hat-making factory. This is “official” art, and the workers he drew look cleaner and healthier than they really were. But Friedmann subtly suggests their pinched faces and thin, hunched shoulders.

Some of the most striking images of workers show “fecalists,” people responsible for collecting human feces and dumping them in pits. Prisoners were crowded into primitive apartments in the ghetto, most of which had no running water or flushing toilets. So waste had to be collected by hand. Jozef Kowner, an important artist who survived Auschwitz, made a painting of fecalists (a man, a woman and a boy) attached to a dung cart in place of horses. They are bent almost double under their burden, and barely look strong enough to pull it. Artist Yitzhok Brauner, who was also successful before the war but died in Auschwitz, made a metal relief of fecalists, pushing and pulling the cart themselves.

People who wrote about their ghetto experiences could hardly find words for their constant, overwhelming hunger. Food was always in short supply, and distribution was complicated. Sometimes prisoners received only 600 calories per day. Many starved to death. Some artworks made in the ghetto discreetly suggest severe hunger. They may have been intended for an exhibition about ghetto life that Rumkowski wanted to present to Nazi officials. So of course the artists had to be careful.

Israel Lejzerowicz, a prominent painter and poet who died at Auschwitz, made a drawing that looks at first glance like a quiet rustic scene. But the scattered figures are Jews searching for scraps of discarded food in garbage heaps. Jozef Kowner showed inmates hunched over small pots of food, staring at them with numb, blank faces. Kowner also suggested the result of starvation: a cemetery, with row upon row of simple mounds, each identified with a card stuck in the dirt.

In the end, Rumkowski’s policy of survival through work didn’t succeed. Conditions at Lodz became increasingly dire. Children and the elderly were deported to death camps en masse in 1942. A number of artists lived until the summer of 1944, but were then deported. Though a handful survived and went on to have long careers, most perished. Rumkowski himself was sent to Auschwitz with his family.

It’s not always known how artworks survived from the Lodz ghetto, and it’s a miracle that any did. Undoubtedly a great deal was lost. The quality of the art in JHI’s exhibition is extremely high: We can only imagine what the murdered artists might have gone on to create. But the works they made as prisoners give a powerful impression of life and death behind the ghetto’s barbed wire.