Is the Trump administration’s website censorship the internet age version of Nazi book burning?

After Trump ordered an end to “gender ideology” in the US, information on trans people began to disappear

After the Trump administration released executive orders banning references to “gender ideology,” research on trans populations began being wiped off of the internet. Graphic by Mira Fox

Essential research on HIV, tobacco use and contraceptive use was removed from the CDC website in January. Information on safety while traveling and international adoption vanished off the State Department’s site. A page on LGBTQI+ inclusion disappeared from the Justice Department. Even an educational page on workplace discrimination was missing from the Labor Department’s site.

All of this information and research was hastily altered or scrubbed entirely from the internet in response to one of President Trump’s many executive orders, issued moments after he took office, declaring there to be only two sexes, male and female, as assigned at birth, and ordering an end to “gender ideology.” Another executive order targeted Diversity, Equity, Inclusion efforts. In response, federally funded agencies rushed to comply.

Previously, these pages had all made references to the LGBTQI+ — lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex — population. After the executive order, however, that vanished; the State Department limited its advice for queer travelers in homophobic countries solely to “LGB” travelers. Other pages, particularly those related to queer working groups formed as part of DEI efforts and scientific research on transgender populations, disappeared entirely.

A pioneering queer institute, wiped from history by the Nazis

This isn’t the first time an authoritarian leader has come into power and, as one of their first moves, destroyed information about transgender people.

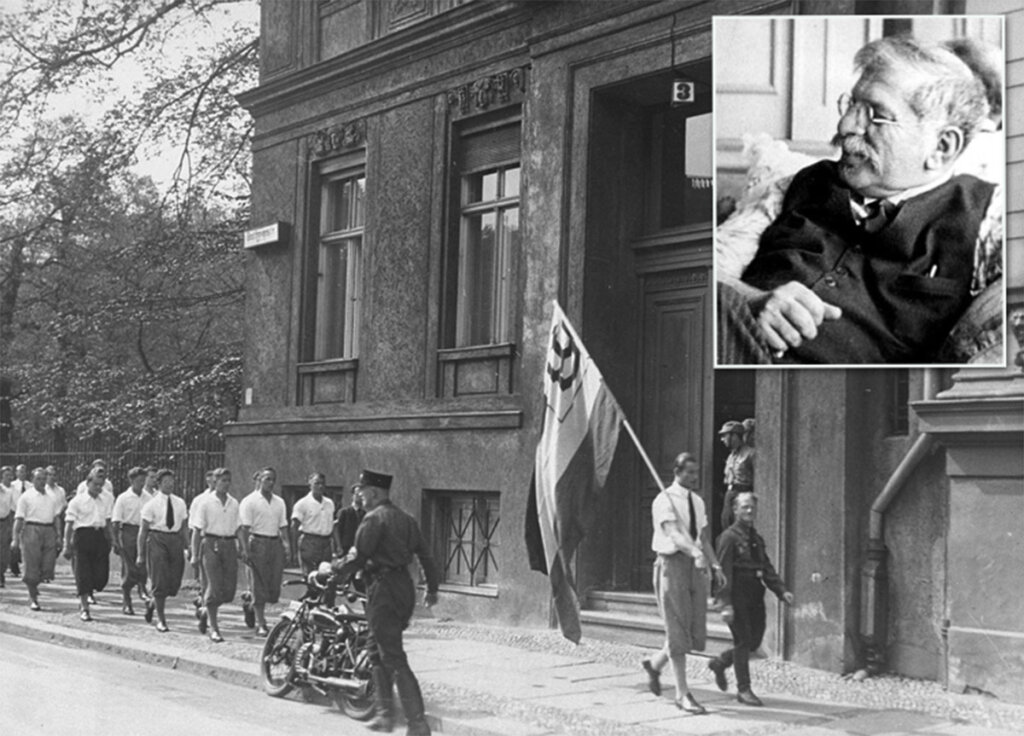

In 1933, following a proclamation of “action against the un-German Spirit,” Nazi youths attacked the Institute for Sexual Research, a pioneering research center in Berlin, run by Jewish sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld. It was the first facility focusing on gender and sexuality; its library was full of groundbreaking research on gender-affirming procedures, hormone therapy and fertility; it also functioned as a cultural hub for feminist activism around suffrage and abortion and even a boarding house for notable thinkers such as Walter Benjamin.

But the Nazis espoused a Volkisch ideology, promoting heterosexual families that operated along strict gender norms — women as mothers and homemakers, men as breadwinners and laborers. They emphasized working the land, and traditional village life. The institute, and the liberal society it nurtured, posed a clear threat. The Nazi students occupied the building for four days before burning its entire library, wiping out decades of research and liberal, queer culture.

“There are days when I think they just have a history book open and they’re going, ‘Next we do this.’ Because it’s just so similar,” said Brandy Schillace, whose book, The Intermediaries, about Hirschfeld’s institute and the rise of Nazism, is coming out in May; we spoke over the phone about the parallels with the present day. “It’s quite uncanny.”

Controlling access to information is a delicate process, though, Schillace said. Take away too much, and people will realize what they’re missing and go looking for it. But carefully curate it, as in the case of the edited federal websites, and people will generally believe that they have access to the full story.

Burning Hirschfeld’s library did not, of course, erase queer and trans people from German society. But it did change the narrative, reducing the information about their place in society — which was a burgeoning one in the liberal Weimar Republic that preceded Hitler’s rise. People were beginning to believe that sexual orientations were not chosen and, as part of nature, could not be faulted or criminalized. Women were campaigning for suffrage and abortion rights. Today, almost no one knows how liberal Germany was before Hitler’s rise.

The power of words

Part of the Nazi crackdown on society, Schillace said, was simply based in language. Vague but appealing terms like “un-German” were leveraged against any groups that did not fit in with the Nazi ideology, starting with small groups of minorities such as trans people and the disabled, and eventually growing to encompass more and more groups.

“They kind of hopscotched from trans people to Jews,” the author said. “Once you start picking one other group and saying this is the Other, you can add people to that.”

Hirschfeld was a member of multiple minority groups as a gay Jewish man. His identity made the Institute for Sexual Research deviant on multiple fronts: It was a source of alternative sexuality, it was run by a Jewish man and it anchored the intellectual queer society of Berlin, an urban metropolis at odds with the Volkisch pastoral ideal. Yet this also made perfect sense; according to Nazi belief, Jews were the root of moral degeneracy, so of course they would be closely connected with a trans institute. In burning the institute, Nazis were attacking not just trans people, but the very root of nonconforming society.

Schillace sees Trump’s executive orders levying censorship against “gender ideology” and “DEI” work operating by similar logic to the Nazi campaign against anything that didn’t conform to a straight, Aryan ideal.

The Nazis burned far more books than just one library full of transgender research. They burned anything they felt was “degenerate,” whether because it expressed an opinion that went against Nazism or because it was simply aesthetically problematic — too modern or abstract, not traditional enough. Un-German became a catchall word that could be deployed against any group, painting them as an enemy of the nation.

Similarly, says Schillace, the Trump administration has “created the sense that there’s an enemy. They like to go after DEI, but they use the term DEI the way the Nazis used ‘un-German,’” she said. “It’s a nice big umbrella they can throw lots under. It’s their clarion call to say we get to decide what’s OK in this nation.”

Rabbi Eliana Kayelle, who works as the Bay Area education and training manager with Keshet, a Jewish organization that advocates for LGBTQI+ rights, agreed — though they highlighted a different term being deployed against trans people.

According to Kayelle, the Nazi ideal of an Aryan represented a very narrow vision; there were strict rules as to what constituted a good, valuable member of society. Any member of what Kayelle terms an “expansive identity” challenged the status quo and represented a danger to the Nazi goals for Germany.

Thinking of 1930s Germany, they wanted to create the master race, the Aryan race, and Jewish identity — any kind of vulnerable group or marginalized identity — went against this idea of a master race,” Kayelle said. “I think that we are seeing similar messaging today around, like we hear from in Project 2025 and the administration, this emphasis on ‘family values — which has no room for identities, values, and families that do not fit within their cisgender, heterosexual, white, Christian boxes.”

The impact of Nazi book-burning today

After the library was burned down, much of Hirschfeld’s and his colleagues’ work was lost forever. But eventually, other researchers and physicians turned to the same subjects, once again exploring hormone therapy as well as gender-affirming surgeries and psychological care.

Today, the politicians and citizens worried about trans rights are able to paint these ideas as new, foreign threats to society. And even this is a sign that the Nazis found success in their book burning — in reality, ideas about trans rights and even gender-affirming procedures aren’t new at all.

“They have no idea that 100 years ago they were actually more forward thinking than we are now,” Schillace said. “It’s been so consciously erased.”

It may sound extreme or alarmist to compare the current executive orders to Nazi Germany. But this, Schillace said, is part of an American inability to believe bad things can happen to us — after all, this is the home of the Ameircan Dream.

“What we have here is a deep, deep myth that it’s always good in America, that people get rich in America, that you go to bed safe in America,” the author said. Yet in Weimar Germany, as well, “everyone thought, well no one will do that. Surely, someone will stop that.”

Yet the impact of the executive orders has already had an impact beyond the websites of federal agencies; worried about a crackdown or loss of funding, major health organizations and hospitals have already ceased providing care to trans and nonbinary youth.

Still, both Schillace and Kayelle warned against giving up; part of what history has forgotten is that trans people in 1930s Germany managed to get much of their research out of the country, where it survived. They fought back. Some of them survived and thrived.

“One thing that feels really important to name as someone who is trans and Jewish in the US right now is that, with this attempt at censorship and erasure of identity and especially with the history, is that we know you can burn books and you can delete words from webpages — but you cannot erase trans people and trans existence,” Kayelle said.