How Marlene Dietrich saved me — or maybe my twin sister — and helped inspire me to become a lifelong activist

Eleanor Rubin’s first brush with fame and activism came unexpectedly during the 1942 Dietrich film ‘The Lady Is Willing’

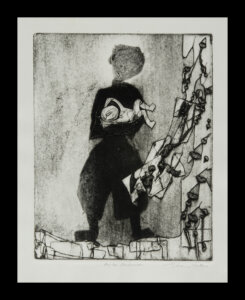

The author (or the author’s sister) with Marlene Dietrich. Courtesy of Eleanor Rubin

Whenever anyone ever asks me, “Where were you born?” my answer is, “Hollywood!” The follow-up question usually is, “Did you know any stars?” “YES,” I always say. “In fact, I was in a movie myself — one with Marlene Dietrich. As a matter of fact, I have photos to help me tell the tale!!!”

In an iconic, glossy publicity photo for the film The Lady is Willing, Marlene Dietrich wears elegant black attire including a dramatic hat with an astonishing cluster of very tall feathers. She is cradling a blonde-haired baby girl in her arms. And, to me, the most important thing is that I am the baby in this photo. Or, it could be my identical twin sister Joanne; she and I are so identical that even to this day we cannot tell which one of us Dietrich is holding.

“The movies like using twins because they can film them alternately and it speeds up production,” our mom Marjorie wrote in an August 1941 letter to her aunt in New York: “They found us through the birth-registry and decided on Elly and Joanne after having interviewed I don’t know how many dozen others. It’s a picture starring Marlene Dietrich and Fred McMurray called The Lady is Willing. Marlene Dietrich plays ‘Miss Madden,’ an actress who finds a baby and wants to adopt it and has a lot of trouble doing it.”

The photo of Dietrich holding one of us was kept with our baby book, along with news clippings, our film contract, copies of our social security cards, as well as my mom’s account of our early Hollywood encounters.

And that’s not the only famous news photo of us related to this film. Another is reproduced in a biography of Dietrich written by her daughter. In it, Dietrich is shown with her leg in a cast. “She tripped while carrying a baby,” the caption reads. “To avoid injuring it, she twisted her body and broke an ankle. The Columbia Studios Publicity Department rejoiced! They brought the baby to the hospital, photographed it with the ‘heroine star’ and knocked the WWII war off the front pages.”

Marlene is later seen in another photo, lying in a hospital bed with a cast from toe to knee, holding me (or is it Joanne?). As our mother tells it, even though Marlene “saved” us, we were too traumatized to continue.

“In-again-out-again- no more movies for us,” she wrote. “After having gone to all the trouble of finding us, of sending a seven-passenger limousine for the children every day, up a suite of 2 dressing rooms as a nursery and getting a special nurse…after doing all that they couldn’t give the kids time to recover from the fall and adjust to the hottest weather we’ve had since they were born.”

There’s also a marvelous vignette of what it was like to have a casual relationship with Dietrich, and for good measure, an encounter with Fred Astaire who walked into their dressing room while they were eating a lunch that Dietrich prepared.

“It’s hard to believe but I think he was more embarrassed than we were, which is saying a lot,” our mom wrote. “We of course offered to scram, but he all but apologized for butting in and disappeared. Isn’t that quite a way to have been confronted with one’s matinee idol?”

The story behind the baby in the picture

The Lady is Willing is a romantic comedy; it’s very light fare and would be just a footnote in Hollywood had it not been for Dietrich’s heroic actions when she protected “the baby” as she fell. But, those photos of us working on that film are not the most important part of our Hollywood story. Behind the cheerful pictures of Dietrich saving me or my sister as we fell, there’s a far more serious, real-world story.

My mom, Marjorie Rosenfeld Leonard, was a Jewish woman born in New York, who took herself to Berlin in 1928 to study to become a child psychoanalyst. In 1931, she met my father, Alfred Leonard (born Levi), a German Jew, born in Mannheim, who was completing his legal studies in Berlin.

Together, they experienced the upheavals of the late Weimar Republic and the rise of Hitler and the Nazis. My mother witnessed the toll that rising antisemitism was taking on her psychoanalytic colleagues, especially Jews; my father was already working for a Jewish legal organization, documenting cases of attacks against Jews all over Germany even before Hitler came to power. That activism and his socialist political views had made him a target of the Nazis long before others understood the dangers. With my mother’s help, he barely managed to escape Germany shortly after Hitler came to power in 1933.

Arriving in America as a refugee, though still on a temporary tourist visa, Alfred joined Marjorie in Los Angeles, where they were married later in 1933. Los Angeles, and especially Hollywood, was quickly becoming a destination for an extraordinarily gifted array of artists, musicians, academics, scientists, and others fleeing Nazi Germany and Eastern European countries. Marjorie’s professional community in Los Angeles included several European-trained psychoanalysts, now themselves refugees, including such well-known figures as Otto Fenichel and Ralph Greenson.

1934 marked a critical moment in my father’s own complex immigration process. He had to leave the country and re-enter from Mexico. Billy Wilder mentored him in this critical process towards becoming a legal immigrant and eventually an American citizen. Wilder, who had made this journey to Mexico himself in order to aid his own immigration status, helped my father by appealing directly to the American Counsel in Mexicali.

Wilder, who himself fled Nazi Germany, actively helped many Jewish immigrants to find opportunities in Hollywood, and he joined Marlene Dietrich in helping Jews escape from Germany. Her salary for the 1937 film Knight Without Armor went towards helping refugees. She also helped to sell war bonds when the US entered the war in 1941 and performed for troops across America and in European war zones from 1941-43. She was even named as an honorary Colonel in the army.

In Los Angeles, Alfred became fluent in English with astonishing speed, but couldn’t resume his work as a lawyer. However, he was able to turn to his avocation of music and supported the careers of émigré musicians like violinist Joseph Szigeti and composer Castelnuovo Tadesco. He re-connected with screenwriter Salka Viertel whom he had known in Berlin, and corresponded with Thomas Mann, who had also fled the Nazis, and lived in Los Angeles during the war years. He became the host of a weekly classical music radio program in Los Angeles and also founded an esteemed chamber music concert series, The Music Guild Concerts.

His important achievements as a convener of world-renowned musicians in Los Angeles included the concerts he organized and sponsored featuring pianist Arthur Schnabel, with whom he developed a special friendship and correspondence. LA became a major venue for classical music when Leonard’s Music Guild featured Otto Klemperer, Maggie Teyte and Elisabeth Schumann.

Repression in Hollywood

Flash forward to Hollywood in the late 1940s when my parents and their friends would come under scrutiny by the House Un American Activities Committee.

As McCarthyism took hold in California, our mother’s name appeared in a publication titled Fourth Report: Un-American Activities in California 1948 Communist Front Organizations, Report of the Senate Fact Finding Committee. Reading this book I discovered my mom’s name (on page 355) with other members of the Los Angeles branch of the Progressive Citizens of America, a group that supported the Hollywood Ten and others accused during the McCarthy era investigations. She told me that she was blacklisted because she had been a member of a “socialist student club” at UCLA in the 1920’s. Meanwhile, my father, who had resumed his activism against the Nazis, had taken on the role of communications director of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, a group that included many major Hollywood figures, and was also monitored by the FBI that was tracking suspected “red” influences.

When my sister and I were about 12 years old, we learned about the importance of friendships and the peril that our parents and their friends were facing. They explained to us that their friend, novelist and screenwriter Albert Maltz, was one of the Hollywood Ten, accused of being a Communist by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Like the other members of the 10, Maltz refused to “name names” when called before the Committee. He was convicted of contempt of Congress and sentenced to prison time. After serving 10 months in prison, he was blacklisted and could no longer work in Hollywood.

Our parents knew that Maltz was living as a lonely exile in Mexico, and asked Joanne and me if we would like to write letters to Albert Maltz, and we did just that. I can’t say that I remember what I wrote or even if he replied. What I remember is myself as a child feeling empathy for a family who had to flee and were separated from familiar surroundings and close friends. And I remember feeling that my parents were in jeopardy themselves during a climate of repression in the Hollywood of the 1950s.

The experience was indelible: I became a life-long letter writer, often to people whose efforts on behalf of social justice felt important. I’ve written letters to Peter Schumann of the Bread and Puppet Theater, to artist and activist Corita Kent, to author and columnist James Carroll, and to historian Thomas Doherty, who wrote about the McCarthy era and mentioned my father Alfred Leonard in his book, Hollywood and Hitler 1933-1939.

And, as an adult in the 1970s, without consciously framing my actions in these terms, I followed my parents’ and Albert Maltz’s example of standing up for what they believed even if it meant risk of arrest. My family supported Daniel Berrigan, a Jesuit priest when he was underground. We were part of a network of families who sheltered Berrigan for months and risked arrest. (Berrigan was wanted by the FBI for destroying draft records as part of the Catonsville Nine.)

I also used my artwork to bring attention to U.S atrocities with iconic images such as my collagraph print My Lai Madonna which was published by David Delinger in Liberation Magazine. Posters using my images (Celebrate Community) were published by the Syracuse Cultural Workers in the 80s and 90s. And, in 2011, Eleanor Rubin: Dreams of Repair, a book of my artwork, was published by Charta with a foreword by Howard Zinn.

I haven’t lived in Hollywood since I left for college at Brandeis University in 1958, but my childhood years in the Hollywood climate I’ve described had a lasting influence: Being held in the arms of Marlene Dietrich and then learning of her own opposition to oppression was an early and indelible part of that experience.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. We’ve started our Passover Fundraising Drive, and we need 1,800 readers like you to step up to support the Forward by April 21. Members of the Forward board are even matching the first 1,000 gifts, up to $70,000.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism, because every dollar goes twice as far.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

2X match on all Passover gifts!

Most Popular

- 1

News A Jewish Republican and Muslim Democrat are suddenly in a tight race for a special seat in Congress

- 2

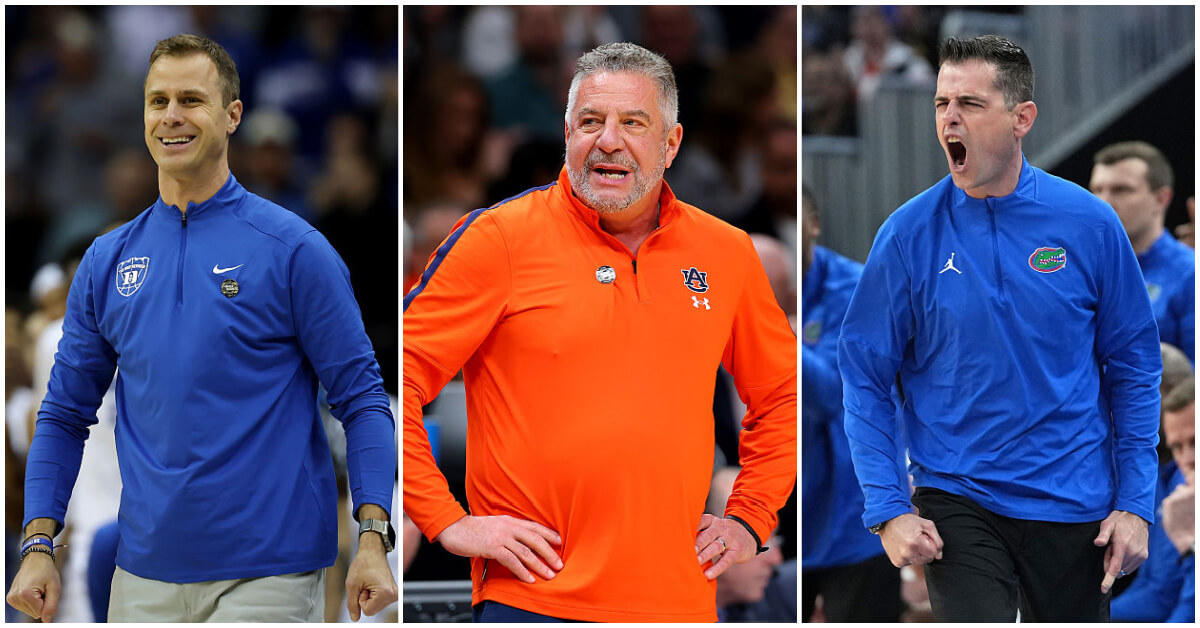

Fast Forward The NCAA men’s Final Four has 3 Jewish coaches

- 3

Fast Forward Cory Booker proclaims, ‘Hineni’ — I am here — 19 hours into anti-Trump Senate speech

- 4

Film & TV What Gal Gadot has said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Texas bakery reportedly becomes first bagel shop to be named James Beard Award finalist

-

Fast Forward ‘That’s Simchas Torah’: The Jewish Val Kilmer moment you might have missed

-

Opinion I co-wrote Biden’s antisemitism strategy. Trump is making the threat worse

-

Fast Forward From ‘October 8’ to ‘The Encampments,’ these new documentaries illuminate the post-Oct. 7 American experience

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.