The secret Jewish history of Alcatraz

As the Trump administration ponders reopening the notorious island prison, we ponder the Jewish ghosts who haunt it

A cell block at Alcatraz Prison. Photo by Getty Images

A reported White House plan, announced May 4, to reopen and expand Alcatraz, the former prison on an island off San Francisco that has been closed for over 60 years, has been dismissed by Izzy Gardon, spokesperson for the California governor, as “Distraction Day again in Washington, D.C.” Scott Wiener, co-chair of the California Legislative Jewish Caucus, tweeted that the notion of a “domestic gulag right in the middle of San Francisco Bay” was an “attack on the rule of law.” Yet Alcatraz, for all its cruelty and bad karma, has been a recurrent theme in American Jewish history and culture.

When Alcatraz opened in 1934, Rabbi Rudolph Coffee, a pioneering chaplain in California’s prison system, ensured that seven Jewish inmates were permitted to observe Passover and the High Holidays.

Coffee organized a separate table in the mess hall with matzo. A typical Seder meal would consist of matzo balls, salami, and salmon. Yet Morton Sobell, convicted atomic spy and co-conspirator of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, kvetched in a memoir that when he was sent to Alcatraz in 1951 due to the gravity of his offense, Rabbi Coffee represented no metzia (lucky break) to prisoners.

Sobell recalled that Coffee had only two topics of conversation during Passover services: himself and his wife. Instead of asking the inmates any questions, he handed each a “couple of pounds of matzos.” The apparent lack of curiosity might have been linked to potential awkwardness associated with any candid replies.

For Sobell’s Jewish co-detainees at Alcatraz included some real nogoodniks, as historians Jenna Weissman Joselit and Robert Rockaway, the latter an expert on Detroit’s Purple Gang of Jewish bootleggers and hijackers, have made clear.

Meyer Harris “Mickey” Cohen arrived on the Rock, as the prison was nicknamed, for evading tax payments. Yet Cohen had made a career out of killing Jewish gangsters. But the American Jewish screenwriter Ben Hecht claimed that Cohen was also an ardent financial supporter of Menachem Begin’s Irgun, a paramilitary organization that operated in Mandatory Palestine between 1931 and 1948.

This swashbuckling version of Cohen has been mythologized in novels by James Ellroy and in the films Bugsy (1991), L.A. Confidential (1997), and Gangster Squad (2013), and those who have played him include Harvey Keitel and Sean Penn.

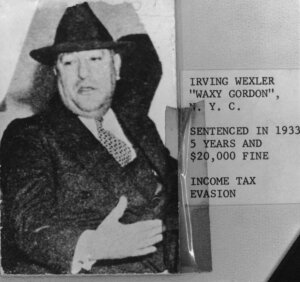

By contrast, little Hollywood glamor surrounded the activities of another Jewish Alcatraz denizen, Irving Wexler, known as Waxey Gordon, a bootlegging and drug peddling cohort of the Jewish mobster Arnold Rothstein who arrived at Alcatraz in 1951.

If Coffee refrained from schmoozing with these hardened cases, Jewish prisoners were communicative with their peers. The historian Alex Tepperman uncovered the story of George Brooks, a Jewish Minnesotan who was sent to Alcatraz for co-organizing a work stoppage among Black prisoners in 1941 at Leavenworth Penitentiary, his former place of incarceration.

Born into an Orthodox household, Brooks’ Yiddish-speaking family arrived in America from the Russian Pale of Settlement in 1881 and were almost all soon pushing drugs. Brooks’ ability to convince African Americans to rebel against the system unnerved prison officials at Leavenworth, which resulted in him being sent off to Alcatraz.

In 1957, Rabbi Julius A. Leibert resigned as chaplain at Alcatraz because he considered prisons a “carry-over from the dim, cruel, unenlightened past” and felt that prisoners needed hospital care rather than punishment.

A more renowned instance of Jewish humanist solidarity occurred at Alcatraz after it closed as a prison. In December 1969, Joel Brooks and Rabbi Roger E. Herst, representing the Northern California division of the American Jewish Congress, moored the newly renamed boat Shalom I to Alcatraz Island.

Brooks and Herst had sailed there to answer a public call for donations from Indians of All Tribes, the Native American activist group who had begun occupying Alcatraz one month earlier to draw attention to U.S. violations of tribe treaty rights.

Brooks and Herst arrived on the fourth night of Hanukkah, and in addition to ten cases of food and blankets, they brought a plastic hanukkiyah for use in a service that symbolized Jewish and American Indian shared experience. An exchange of gifts followed as well as “Indian and Jewish folk-dancing.”

Brooks later commented to a reporter that Jews “know what it means to be dispossessed of their land”; Herst commented that Hanukkah is a “festival of liberation from oppressive forces” and he hoped that Alcatraz would become an Indian symbol “of that same struggle.”

As historian Avery Weinman noted, this episode showed that American Jews and Native Americans “looked to each other as sources of mutual empowerment.” Perhaps for this reason, on the island to treat the masses of Native Americans struggling against the harsh weather, six of the seven volunteer doctors were Jewish.

Simultaneously, the San Francisco Jewish Community Center and local university Hillel branches hosted events to support the Alcatraz Indians with tzedakah. With Alcatraz as a nexus, a shared history of genocide also linked Jews and American Indians, according to the University of Chicago anthropologist Sol Tax.

Whatever the psychological motivation, Alcatraz has acquired an aura of Yiddishkeit, as in a multivolume series of comic books written by Rabbi Avraham Ohayun and illustrated by Yehuda Yisrael.

These books tell of the fictional tsuris of David Salah, a rich, pious Chicagoan who is framed for murder and receives a life sentence at Alcatraz, until the Mossad try to liberate him.

Yet as the Jewish literary critic Janet Burstein implied, perhaps the most emotionally incisive statement in prose about Jews and Alcatraz was by the Jewish author Grace Paley. In an early short story collection, The Little Disturbances of Man, Paley uses a simile when describing the painful but indissoluble bondage of maternal love, with the short fat fingers of her little son gripping her “like a black and white barred king in Alcatraz.”

In 2023, in a less domestic context, news reports explained that two teenaged brothers, congregants of San Francisco’s Temple Emmanuel, joined the annual 1.5-mile Alcatraz Swim for Sight, with participants, including two rabbis, braving the cold, open waters of San Francisco Bay from Alcatraz to the city to raise money for a vision impairment charity.

One of the boys referred to the swim as a Shehechiyanu moment, or feeling of gratitude for being alive and the miracle of the present moment. No less adamant in pursuit of his own Shehechiyanu moment, another local swimmer, the octogenarian businessman Levy Gerzberg, has swum dozens of times between Alcatraz and the mainland, often raising funds for children’s causes.

This determination to see Alcatraz as an opportunity for tzedakah is a Jewish optic that will surely endure, whatever inhumanity the current White House administration may inflict on the site.