The towering Jewish critic who taught me to grok art and hate Picasso

After Max Kozloff died at 91, a New York community came together to remember and to mourn

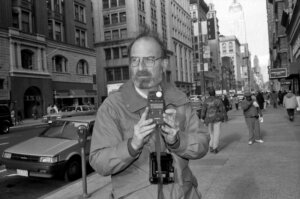

Max Kozloff in Battery Park, standing in front of Ned Smyth’s Upper Room, 1987. Photo by Pedro Meyer

When I was a young teen in the 1970s, my artist mother told me that the dad who walked me home after I’d babysat for his son was a “famous Marxist critic.” I was 13 and had no idea what that meant — and was too intimidated to ask. Only decades later at Max Kozloff’s memorial after his death in April at age 91, did I grasp his significance for American art, the Jewish connection to his “Marxist” analysis and his work’s unexpected meaning for my own life.

Working as a babysitter for Max and his also-famous painter wife, Joyce Kozloff, was a vivid part of my coming of age amid the buzzing 1970s downtown creative scene. My late artist-writer mother, Judy Seigel, knew Joyce from feminist art activist circles in a city then raucous with graffiti, hippies, happenings, muggings and garbage. For the going rate of $1 an hour, I watched a bunch of kids, and even worked for legendary journalist Seymour “Sy” Hersh. Uninterested in his Pulitzer prize renown, I only wanted his baby to stop crying. (Freaked, I phoned my mother, who told me to pick up the infant and walk around. It worked.) Since the Hersh’s lived near me in Greenwich Village, I was able to walk home just fine on my own.

Back then, though, the stretch between my Village home and the Kozloff loft in pre-gentrified Soho was a dark, empty no man’s land. So Max escorted me the ten blocks home. More than six feet tall and slightly rumpled, he was genial but didn’t talk much — and I had little to say to this towering intellectual dad. My interests were vintage clothes, my violin, horses, Carole King and (later) the midnight Rocky Horror Picture Show screening at the Waverly Theater. So we walked in amiable, if slightly awkward (for me) silence, the occasional car swooshing by in the quiet.

A half century later, his standing-room-only memorial at the Greenwich Village Funeral Home doubled as a surprising education in 20th century art controversies and a return to the people and places of my youth. The vibe was cozy, elder haute Boho with folks leaning up against walls in the stained glass-windowed Bleecker Street chapel. Rabbi Samuel Kastel, the hospice chaplain who visited during Max’s struggles with Parkinson’s, opened with a quasi landsman apologia. “Max was not observant,” Rabbi Kastel allowed. “But he was deeply Jewish in how he approached the world and his work. He looked at things from every angle and outside the box.”

After he moved to New York in 1959 for doctoral studies at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, he wrote increasingly influential essays for The Nation, Art International and elsewhere, exposing the hidden political, moral and capitalist dimensions that he saw as inseparable from the painted canvases.

Bucking orthodoxy, his 1972 essay “Cubism and the Human Comedy” for ARTnews skewered Picasso and his revered ilk for painting disjointed naked female figures that were “monstrous,” “ugly” and “misogynistic.” This iconoclastic analysis laid crucial groundwork for “women’s” and other kinds of art to gain acceptance. Most notably in his 1973 “American Painting During the Cold War” for Artforum, he debunked the Formalist belief that modern art is only about pure form, color and innovation. Au contraire, Max interpreted Abstract Expressionism’s claim to be devoid of content except expressing “eternal humanist freedom” to drip, smear and splatter color on surfaces as “benevolent” cultural propaganda serving “burgeoning claims of American world hegemony.”

As publisher-scholar Christopher Lyon’s eulogy summed it up: “What Max always asked is not, ‘What should we be paying attention to?’ but rather, ‘What are we missing?’”

But targeting the New York creative elite’s power and financial structure was another matter. After he became the executive editor of Artforum in 1974, Max challenged nepotism and gallery advertiser sway over editorial content, while publishing essays on the sociopolitical aspects of art. New York Times critic Hilton Kramer’s screeching backlash, “Muddled Marxism Replaces Criticism at Artforum,” sparked a page of letters to the editor defending his camp’s view that universal belief in ‘objectivity’ was itself another form of ideology promoting a particular point of view. Though a widely understood concept today, the claim that “objectivity” is culturally manufactured rather than an unchanging external truth was radical back then.

Was Max silently mulling the ferocious Formalist fracas as we strolled west on Houston Street? I don’t know; we never talked about it.

After the publisher fired his compatriot editor-in-chief, Max resigned in 1977. Reinventing himself, he built a new life as a highly-regarded photographer, photo critic, author and curator. His 2002 book and exhibit at the Jewish Museum, ”New York: Capital of Photography,” provocatively proposed that a distinct “Jewish sensibility” explains why so many great 20th century photographers, such as Weegee and Diane Arbus, were Jewish. His theory that a ‘funky” urban outsider status explained their success behind the lens tweaked some sensitivities, Jewish and not. As Max acknowledged in a New York Times interview: “Jewish photographers have spent their careers trying to escape these parochialized terms. ‘They think I’m putting them back into a ghetto. But that’s not my intent.”

But on the sunny April day after mourning family and friends left the memorial and strolled to the gathering at the Kozloff Soho loft, the intense passions of those controversies were all bygones. I felt a comforting familiarity entering the airy floor-through, where I once lingered in Joyce’s back studio space pondering her large scale “pattern and decoration” paintings after their son Nicky (now Nikolas) went to sleep.

I thought the colorful triangles, squares and zigzag designs were lovely. That was the problem, my mother had explained of Joyce’s battle for recognition (i.e. male) for this supposedly “feminine” aesthetic, which taste arbiters dismissed as mere domestic “craft.” As a teenager I was more concerned with smashing the “male gaze” obsession with nudie female figures, since it affected me daily on the streets in leering catcalls from men. But I got the idea that pleasing creations including quilting, crochet, and ceramics that give joy merit esteem, too.

As Joyce recently reminded me, my mother reported on this defense of design for the pioneering Women Artists News, which she co-founded as editor with publisher Cynthia Navaretta in 1975. Digging into the publication’s 17-year archive, I was thrilled to find my mother’s interview with Joyce at the loft that year exploring why “decoration is a dirty word.” Decrying (male) critics who wield “sweet,” “pretty,” “decorative” and “lyrical” as “bad words,” Joyce concluded: “I think prohibitions like this are primarily sexist.” Today her work is celebrated as pivotal to the now-acclaimed “pattern and decoration” movement.

At the loft reception, I bumped into octogenarian artists of my youth, including multi-media creator Judith Henry, whose two daughters I also babysat for on the floor below. Though 50 years have passed and she now has five grandchildren, she looked exactly the same with her pixie haircut, smooth skin and soft voice.

And there was recently-pantheonized Judith Bernstein, who joined my mother as a speaker on a 1978 Artists Talk on Art panel, “It’s all Three Inches High in Artforum” about size and dimension. In another talk, on eroticism in art, Bernstein objected to the fact that the political implications of her art were overlooked.

This winter, elegiac coverage greeted Bernstein’s “Public Fears” mini-retrospective at the prestigious Kasmin Gallery, including her 1970s charcoal drawings of giant disembodied hairy screws — phalluses. Do people get her art today? I asked. “It’s good,” she said, smiling behind chunky glasses below a spiky black updo. “I’m getting a lot.”

A few weeks after the memorial, Joyce remarked to me how moved she was by the tributes, with cards and letters still coming. Yet in recent years as Max was battling illness, he felt forgotten. “I wish he were here to see it,” she lamented. “It’s sad.”

Haunting words. Is it the nature of our lives that some things remain ever out of reach? My father is gone and I miss my mother who died eight years ago with Alzheimer’s, though incredibly she never forgot that she hates Picasso. I didn’t think to ask why. Sometimes, it’s not too late. Thank you, Max Kozloff, for explaining it.