Kinky Friedman has been gone a year, but his family’s summer camp lives on

Tom and Min Friedman’s Echo Hill Ranch is enjoying a second life as a camp for the children of Gold Star families

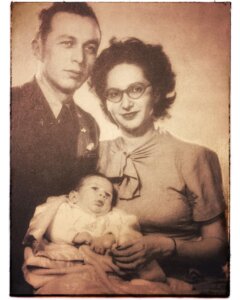

The Friedmans at a picnic bench with Laddie, the dog. Courtesy of Echo Hill Ranch

The late Kinky Friedman honed his songwriting and performance skills at a Jewish summer camp in the Texas hill country started by his parents.

Tom and Min Friedman opened Echo Hill Ranch in 1953, and for 60 years it instilled tikkun olam, the Jewish duty to repair the world, in its campers. Each week one of the children was tasked with giving a sermon. Challah baked at the camp was served at the first meal of shabbos where campers wore white shirts and pants.

“Echo Hill was like a maypole for our family,” Kinky’s brother Roger, 76, told me. “It sort of held the family together.”

The three Friedman siblings grew up at the camp — first as campers, then as counselors. Roger and kid sister Marcie served as directors. It should come as no great shock that Kinky did not, though he did raise funds and sang for the campers. “Get Your Biscuits in the Oven and Your Buns in the Bed” and “Asshole From El Paso” were not included in his camp repertoire. But Ol’ Ben Lucas, which he wrote when he was 11, certainly was:

Ol’ Ben Lucas/ had a lot of mucus/ Comin’ right out of his nose/ He picked and picked/ till it made you sick/ But back again it grows.

Marcie is now 64 and getting ready to retire from the U.S. State Department after serving in Afghanistan and other diplomatic outposts. Roger, who earned a PhD. in psychology, has already retired from his clinical practice in Maryland. In addition to his fame fronting the irreverent country western band Kinky Friedman and The Texas Jewboys, their older brother wrote a slew of mystery novels, including one set at Echo Hill, before he “stepped on a rainbow” in June 2024. Kinky Friedman lived at Echo Hill Ranch for the last 39 years of his life.

Tom and Min Friedman, who grew up in Chicago, were no slouches either. They met at the Jewish People’s Institute, a cultural center on the city’s west side. During World War II, Tom flew 36 bombing missions as a navigator in the Army Air Corps. After the war he took a job in Houston at the Southwestern Jewish Community Relations Council, where his duties included monitoring developments in the region “of a potentially Fascist nature.”

The family moved from Houston to Austin so Tom could finish his PhD. in psychology. He then taught at the University of Texas.

Minnie earned a master’s in speech therapy and worked for school districts in Houston and Austin. According to Marcie Friedman, Minnie was the first camp director to be certified by the American Camping Association (ACA) in Texas. At the summer camp the Friedmans were known as Uncle Tom and Aunt Min.

A cutting edge approach

The 266-acre Echo Hill Ranch is nestled in a green valley in the Texas hill country. The locals in Kerrville used to refer to it as “the Jew camp,” Marcie said. Camp Young Judea, a Conservative movement facility, was less than ten miles away but, according to Roger, there was no interaction between the two camps.

Kids at Echo Hill swam in a creek that feeds the Guadalupe River — the same river that flooded in early July of this year, taking more than two dozen lives at a Christian girl’s camp. At Echo Hill, children helped care for and ride the half-dozen horses that roamed free around the property.

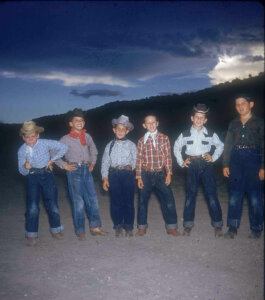

Every morning the boys or girls from one of the bunks would climb to the top of Echo Hill, which is 2,300 feet high, and call out, waking the rest of the camp as their voices echoed through the valley. The camp had a child-centered, non-competitive approach to camping. There were no color wars here.

“My mother and father were very much at the cutting edge in the 1950’s, looking at child development,” Marcie Friedman told me. “My mother was very committed to camping as an important way to help children develop and socialize.”

“She really believed that the diaspora Jews needed to be rebuilt and reconstituted,” Roger Friedman said of his mother. “And that doing that through a vehicle like a summer camp was a great idea.”

Bill Scholl has written a memoir of his time at camp titled The Rabbi, Kinky and Me. The rabbi in the title is a reference to the late Jimmy Kessler, who created a booklet for Echo Hill’s Friday night services when he was a camper, and went on to become a rabbi. Scholl came to Echo Hill from a small town in Louisiana.

“For those of us who grew up in little towns in Texas and Louisiana and had never been around Jewish kids, [Echo Hill Ranch] was a revelation,” said Scholl, a retired businessman who now lives in Zurich.

Hyman Penn grew up in Newgulf, Texas, a town of less than 2,000 residents where his was the only Jewish household. The son of Holocaust survivors, Penn, now a retired pediatrician, has been performing as a magician since 5th grade. He’s come back to the camp since his college days to teach kids magic tricks. A 10-year-old Echo Hill camper provided his stage name, Hydini.

“I was not an athlete growing up,” said Penn. “But it didn’t matter at that camp because everybody was somebody at Echo Hill… I was still important there and I think that really helped me grow and become who I am.”

Aaron Fink, who has a psychiatry practice in Houston, said attending camp at Echo Hill Ranch and serving as a counselor there had an impact on his career path.

“The camp always included kids who had emotional and behavioral problems that maybe would not be tolerated at other camps,” Fink said. “When I worked there, I always found those kids to be the most interesting to work with and that sort of cemented my interest in going into child psychiatry.”

Nothing like Echo Hill

Min Friedman passed away in 1985. Marcie Friedman helped her father run the camp through the 1990’s. After Tom died in 2002, Roger Friedman and his wife Roz Beroza took over while holding down full-time jobs back in Maryland.

They developed a creative shabbos program linked to nature and conservation, holding campouts on Friday night where candles were lit and blessings were recited around a campfire. The kids were encouraged to talk about celebrating the Sabbath in the woods. They did environmental remediation such as dredging the river and cutting down young cedar trees that deprived hardwood trees of water.

After the 60th reunion in 2013, a decision was made to close Echo Hill.

“It was a heartbreaking decision for me,” Roger told me.

The camp remained shuttered for eight years until Marcie and a member of the Special Forces named Bobby McBride re-opened it in 2021 for so-called Gold Star kids — kids whose parents perished in the course of military service.

Since then, Echo Hill Ranch has been a Gold Star camp, though it doesn’t adhere to the strict Gold Star criteria. Children whose parents died in training or by suicide are eligible, as are the kids of first responders who died on the job. Fifty kids come for each 10-day session. There is no charge for the Gold Star kids.

This summer the camp was on hiatus, partly because the Echo Hill community was still grieving for Kinky, Marcie said, who’s been working for the State Department remotely from the ranch. She was also concerned that she might be called back to Washington in June.

Lt. Colonel McBride, a helicopter pilot who served in Iraq during the 2006 to 2007 surge, met Friedman when they were both enrolled at the National Defense University at Fort Bragg in North Carolina, which happens to house the Special Forces headquarters.

“These families have had a lot of help, but they didn’t have anything like Echo Hill,” McBride said of the Gold Star families.

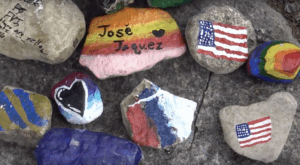

McBride’s wife Lauren was also a Special Forces helicopter pilot and a graduate of West Point. She told him about a rock cairn near the military academy created to honor fallen soldiers. McBride came up with the idea of creating a similar shrine for the parents of the Gold Star campers at Echo Hill.

During each session children find a rock to paint in honor of their lost parent. They make the 20-to-25 minute climb up Echo Hill and place them lovingly in a special stone bed prepared for the ritual. It’s reminiscent of the Jewish ritual of placing a stone on a grave when visiting the resting place of a loved one. The ancient custom is said to have originated as an effort to keep the soul of the departed down in this world and prevent demons from getting into the graves.

The alumnae of Echo Hill’s Jewish days still come to volunteer.

Dr. Penn said he’ll never forget the year a kid who came up to him after his magic demonstration.

“‘My father used to do magic for me,’” Penn recalled the kid saying to him. “It just broke my heart when he said that.”