Sam Sussman’s novel is about his Jewish mom and the teasing possibility that Bob Dylan is his dad

In “Boy from the North Country,” a writer turns a real-life mystery into an exploration of parenthood and inheritances

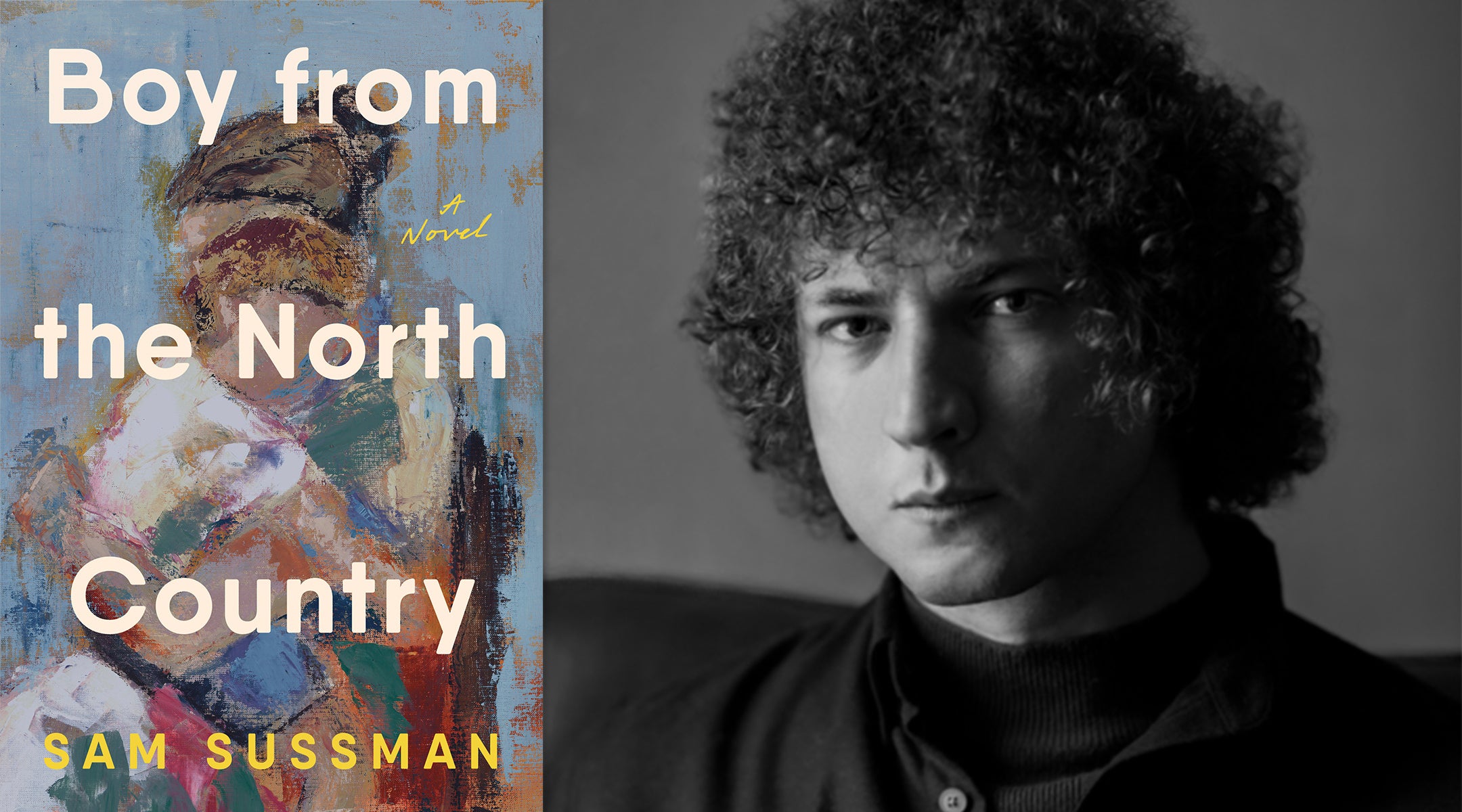

In “Boy from the North Country,” Sam Sussman writes about his mother’s real-life romance with Bob Dylan. Photo by Penguin Random House; author photo by Ben Kaplan

(JTA) — Sam Sussman’s debut novel, “Boy from the North Country,” revolves around a mystery: Was Bob Dylan, the singer and Nobel laureate, the narrator’s father?

Sussman could have written this tale as a memoir, an expansion perhaps of the 2021 essay he wrote for Harper’s Magazine: “The Silent Type: On (Possibly) Being Bob Dylan’s Son.” His mother Fran, a former actress and art student, spoke occasionally and usually sparingly about her romantic involvement with Dylan when she was in her twenties. She told him, in a story confirmed by his aunt, that she and Dylan met once again nine months before he was born in 1991.

It’s a backstory worthy of a paternity suit, or perhaps a “Serial”-type podcast that tries to get to the truth of the matter.

Instead, Sussman chose to continue the story as fiction, writing of a mother who came of age in the gritty New York art world of the 1970s, and a son, named Evan in the novel, sorting through questions of identity, grief and Jewishness.

Sussman, 34, insists that the novel is less about DNA than about something both more intimate and more elusive: how we turn life into art, and how we honor the people who shape us.

“A memoir is about the writer,” Sussman told me in a recent conversation. “A novel is about the writing.” For him, fiction is the medium not for proving lineage but for capturing what he calls “the wisdom and resilience” of his late mother. She died eight years ago, but her voice, philosophy and Jewish sensibility animate nearly every page.

In real life and the novel, mother and son lived in a farmhouse near upstate Goshen, New York. His mother and the civil rights lawyer he’d grown up thinking was his father divorced when Sussman was 2. In the book, Evan describes his mother’s complicated romantic life, and the various men who entered their lives through his childhood and adolescence, some staying longer than others.

Dylan is a vivid presence. Through Evan’s mother’s recollections, we glimpse the singer in his early 30s, taking art lessons with the painter Norman Raeben and wrestling with the songs that became the Dylan album “Blood on the Tracks.” For Dylanologists, it’s catnip. For Sussman, it’s also a chance to situate Dylan, born Robert Zimmerman, in a Jewish artistic milieu — bohemian, postwar, steeped in the theater world of Stella Adler, the acting coach and daughter of a legendary Yiddish theater family, and in the artistic milieu of the rabbinic Raeben, whose father was the Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem.

If Dylan offered the author one kind of inheritance, biological or artistic, Judaism offered another. Growing up in Goshen, Sussman was often the only Jewish kid in the classroom — and sometimes the target of antisemitism. (It didn’t help that his classmates aped their parents’ prejudices about the Hasidic Jews who lived in nearby Kiryas Yoel.)

His mother, a holistic health practitioner untethered from institutions but steeped in Jewish texts and values, modeled a spiritual practice that was at once idiosyncratic and deeply rooted. She often told him, “We’re here to take the pieces of the universe we’ve been given, burnish them with love, and return them in better condition.” It’s a credo that echoes the kabbalistic idea of “shevirat ha-qelim,” which posits that it is the human project to repair the “broken shards” of God’s creation and restore them to their pure, unbroken state.

“She wasn’t affiliated with a synagogue,” said Sussman, a co-founder of Extend, an NGO that introduced Birthright Israel participants to Palestinian human rights activists. “But she had a profound relationship to Jewish spiritual and ethical traditions, and she gave that to me.”

The Dylan question — was he or wasn’t he? — hums like background music in the book. Strangers and teachers tell Evan that he resembles Dylan (as does Sussman, who lately sports a Dylan-esque Jewfro). The narrator’s mother describes Dylan’s visits to her walk-up in Manhattan’s East 70s, at a time when he was still married to his first wife, Sara. Mother and son attend a Dylan concert in Bethel Woods, on the site of the original Woodstock festival, where she insists that they try not to contact the singer.

Even as she lies dying of cancer, Evan’s mother keeps silent about whether Dylan was or could have been his father.

“I looked at my reflection and understood that my mother’s refusal to discuss him was one prolonged act of protection, not against the answer but the question,” writes Sussman. “Her desire had always been for me to become my own person in my own way.”

In our interview, as in the book and the Harper’s article, Sussman is content not to supply or even pursue the answer readers might crave. To do so, he says, would betray the emotional resolution of the story, which is about moving past fixation with celebrity toward a deeper appreciation of the woman who raised him. Much of the book takes place at Evan’s mother’s bedside, as the boy she raised mostly alone must learn to be her caretaker.

“Samuel Beckett said you have to find the form that fits the mess,” Sussman explained. “For me, that form was a novel.”

Her mother’s philosophy about burnishing the broken pieces of the universe shapes not only the novel but Sussman’s approach to grief. The author, who splits his time between his mother’s longtime apartment in Manhattan — the same one where she and Dylan would discuss art, music and Dante’s Inferno — and his childhood home outside Goshen, says the novel allowed him to collapse past and present, and to redeem “the most difficult piece of the universe” he’d been given: her loss.

When I asked if he had sought a reaction from Dylan or his handlers, or if he hoped the musician, now 84, might hear about or respond to the book, Sussman shrugged. “I wrote the book for my mother,” he said. “I didn’t write it for Bob Dylan.”

On Sept. 16 at 6 p.m. ET, join Sam Sussman, author of “Boy from the North Country,” for a conversation with Menachem Kaiser, whose memoir “Plunder” won the 2022 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature. Register here for the free Zoom event, the latest in the Folio series hosted by New York Jewish Week and UJA-Federation of New York.