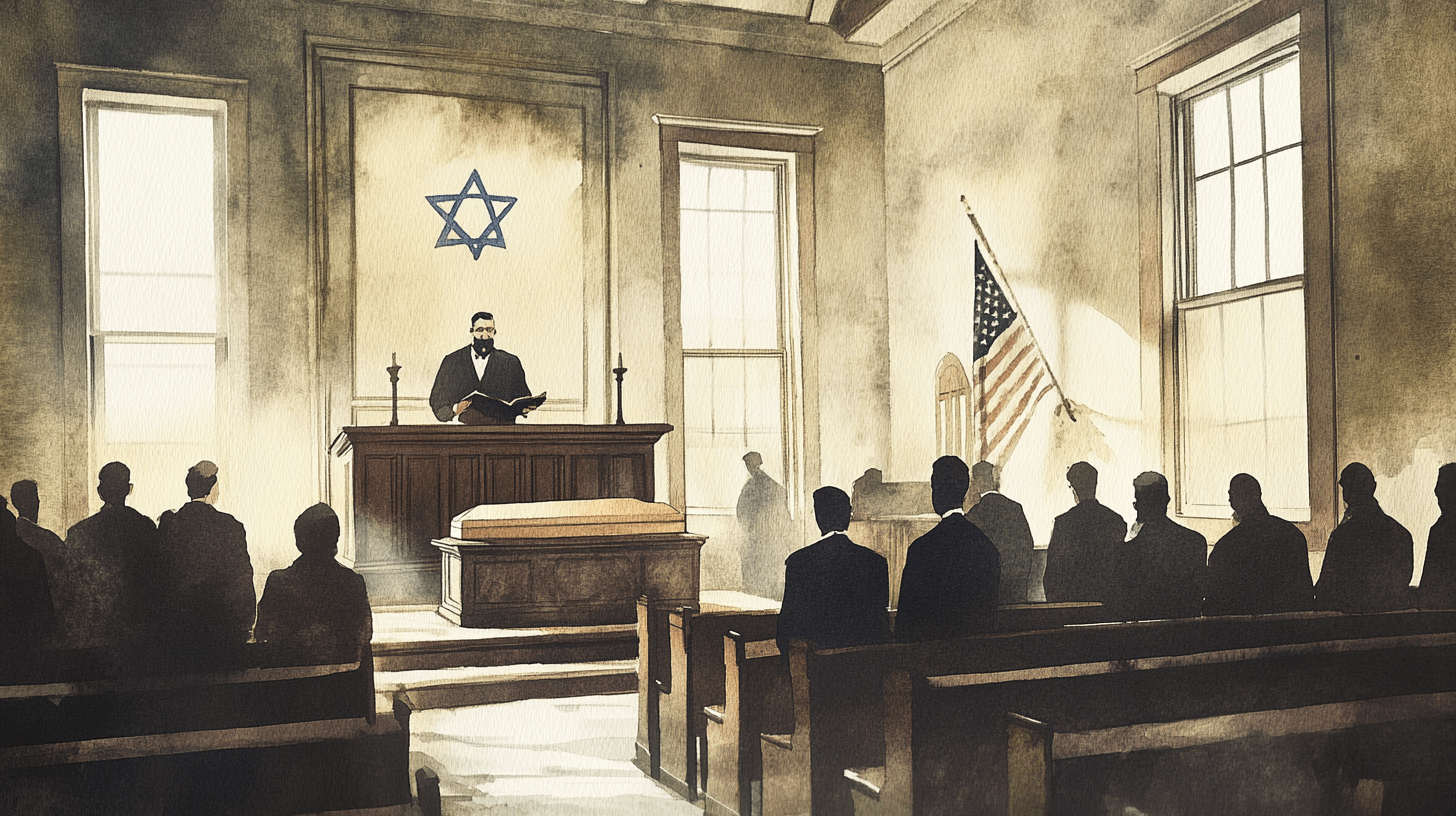

How one man’s burial brought Jews and Christians together — and what it still teaches 120 years later

The 1915 service for Harris Cohn revealed something timeless about American religion: that devotion, in any language, can be shared

Graphic by Benyamin Cohen/Midjourney

“The beautiful little synagogue was filled to capacity,” the Tupper Lake Herald reported on February 12, 1915. “Many were there who had known Mr. Cohn for the past twenty years — old Adirondack pioneers… The air was heavy with tears as Rev. Boyd of the Episcopal Church lifted a Hebrew prayer book given him by Mr. Cohn a few years ago.”

The man they gathered to honor was Harris Cohn, an early Jewish resident of Tupper Lake, New York. His funeral filled the small Beth Joseph Synagogue, the same wooden building that still stands today, now celebrating its 120th anniversary.

Just a decade earlier, in 1904 or 1905, local families — peddlers, merchants, and new immigrants — had pooled roughly $450 to build it, holding Hebrew school classes in the town hall while waiting for carpenters to finish the sanctuary. In 1911 they purchased an acre for a cemetery beside the Methodist burial ground.

Cohn, the paper wrote, was “the personification of honor, truth, and integrity” — a man of “deep religious convictions… the firm believer of righteousness, benevolence, charity and prayers.” His “belief in God,” the editor added, “was so ideal, so far elevated above all earthly things, that no sacrifice was too great to show and prove his devotion to his Maker.”

Rabbi S. Freedman of Beth Joseph led the prayers, chanting the memorial service in Hebrew. Then the local Episcopal minister rose to speak.

He held up the worn Hebrew prayer book Cohn had given him and said, “I prize this book so much, for Mr. Cohn was a man whom I admired and with whom I established a strong and lasting friendship.” Then he turned to the young people present and urged them “to hold fast to whatever denomination they were reared under,” reminding them that conviction and faith come from devotion to one’s own tradition.

The rabbi had spoken of religion not as a convenience but as “a deep solace to the soul.” The minister, moved also by faith, echoed it in his own words. Jews and Christians mourned together. When the eulogies ended, the mourners recited kaddish, an ancient prayer offering comfort and acknowledging God.

I came across this article, digitized through the New York State Historic Newspapers archive, while researching Jewish life in nearby Ogdensburg and Massena. I paused to hold this memory. I had been tracing the histories of small-town synagogues — some now closed, others still standing in places like New York’s North Country and across the Midwest. In Tupper Lake, as in so many places, Jewish life grew quickly and then thinned with time: by 1913 a Sisterhood had formed; by 1914, a lodge of the Independent Order of Brith Abraham met in the synagogue twice a month; and by 1918, Beth Joseph had joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. Each step spoke to a community that saw itself as part of something enduring, even in a place far removed from America’s largest Jewish centers.

The story of Harris Cohn’s funeral felt familiar. I had come across many such moments in small-town American history, and it revealed something essential that runs through so many of these places: a moral imagination larger than their size.

These were communities where faith was not theoretical. Jews and their neighbors depended on one another — through long winters, economic hardship, and the isolation of distance. Synagogues, often built by peddlers and storekeepers, became civic landmarks as much as houses of worship. A century later, when we look back at the geography of American Jewish life, we see that its reach was far wider than today’s metropolitan map suggests. For every major center of Jewish population, there were dozens of smaller congregations that carried the same prayers into fields, factory towns, and forest settlements.

It’s easy to forget that these rural sanctuaries once embodied outposts of Jewish belonging. Their stories are rarely told, overshadowed by the better-known narratives of New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles. Yet in towns like Tupper Lake, Judaism became part of the spiritual language of the whole community.

That is what moved me about the 1915 funeral. The newspaper account wasn’t written for a Jewish audience. It was published for the whole town, describing the service with reverence and curiosity but without exoticism. The boundaries between communities blurred, and what emerged was shared moral clarity: the belief that dignity, faith, and friendship can withstand every division.

There is something profoundly Jewish in the humility of that service. The simplicity of the synagogue, the equality of all before death, the act of remembrance itself — all mirror the same values I have seen in Jewish life today. In Tupper Lake, that ethos endured. By the 1930s, Beth Joseph opened its doors to patients from the nearby state hospital for Passover Seders, and in 1925 Rabbi Freedman — the same clergyman who eulogized Cohn — offered words of comfort at a Masonic memorial for a Presbyterian pastor. The boundaries were always more porous than history remembers.

Beth Joseph’s continued presence in Tupper Lake is a kind of quiet miracle. This year marks its 120th anniversary — a milestone few rural synagogues reach. The synagogue testifies that Jewish life has, at various times and places, reached into nearly every corner of America, leaving behind something worth remembering: the habit of neighborliness, the belief that God is present wherever people honor one another.

When Rev. Boyd lifted that Hebrew book at a funeral in 1915, he could not have known how far that gesture would travel. But in reading it more than a century later, I think of it as an act of faith in its own right. A Christian minister, holding the sacred words of another tradition, showing them to his townspeople with tenderness. That is a kind of sermon that still preaches.

The story of Harris Cohn’s funeral is not about a vanished world. It is about a world that, at least for one afternoon in the Adirondacks, revealed its best self.

The prayer book may no longer exist, but its lesson remains open: that the sacred is never confined by walls, and that remembering each other is itself a holy act.