Photo EssayHe documented a changing Jewish world, and the Jewish world changed him

Photographer Bill Aron’s work is on display at a retrospective at the American Jewish Historical Society

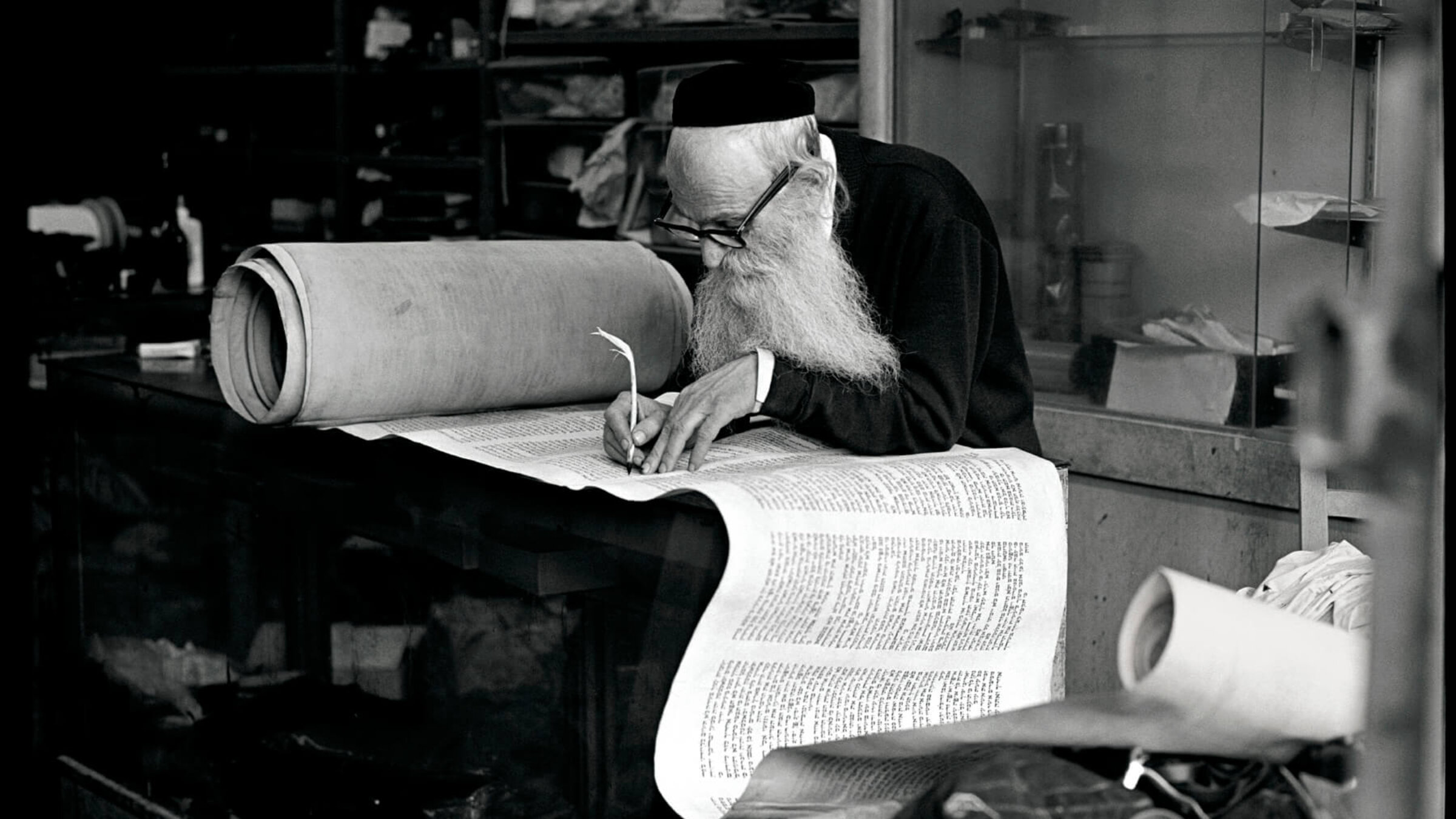

Rabbi Eisenbach, Scribe, Lower East Side, 1975. Aron said the rabbi, who he had been spending time with, had refused to allow his photo to be taken. One day, Aron snapped the photo without asking and, when the rabbi looked over his glasses at the sound of the shutter, ran away. Later, he brought the print to show the scribe, who was delighted by it in the end. Photo by Bill Aron

Photo EssayHe documented a changing Jewish world, and the Jewish world changed him

Photographer Bill Aron’s work is on display at a retrospective at the American Jewish Historical Society

“I have to tell you,” Bill Aron told me as he walked around The World In Front of Me, a retrospective of his photography at the American Jewish Historical Society, “my photography allowed me to walk into rooms I might never have otherwise walked into.”

We had just looked at some of his work documenting Jews on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the 1970s and ’80s: a sofer bent over a Torah scroll, a glowering rabbi with imposing eyebrows, a Hasidic wedding in the Bobover movement. Each photo begat the next; when he showed a reticent subject the results of his film, they would invite him back to take more.

Aron has become known for his work documenting Jewish communities around the world — his first book, From the Corners of the Earth, shows Jewish life in New York, Los Angeles, Cuba and the then-Soviet Union. His next, Shalom Y’all, was the result of a decade spent in the lesser-known Jewish communities of the American South.

His images are joyous and warm, portraits of resilience and invention, not dour investigations of poverty and antisemitism, offering respect to each subject he was able to meet through his work.

But his camera didn’t just change his access to the communities he documented; it changed Aron’s own experience of his Judaism.

A series of photographs shows scenes from the New York Havurah, a lay-led, egalitarian Jewish religious movement: A rabbi stands in reverent contemplation under his tallit in a misty forest; a child smiles from her father’s shoulders during a Shabbaton. Aron was a member in the ’70s, which is how he found himself in the middle of those scenes. But, he said, he didn’t grow up observant, and without his camera, while he might have been a member, he would have been “a much more passive one,” he said.

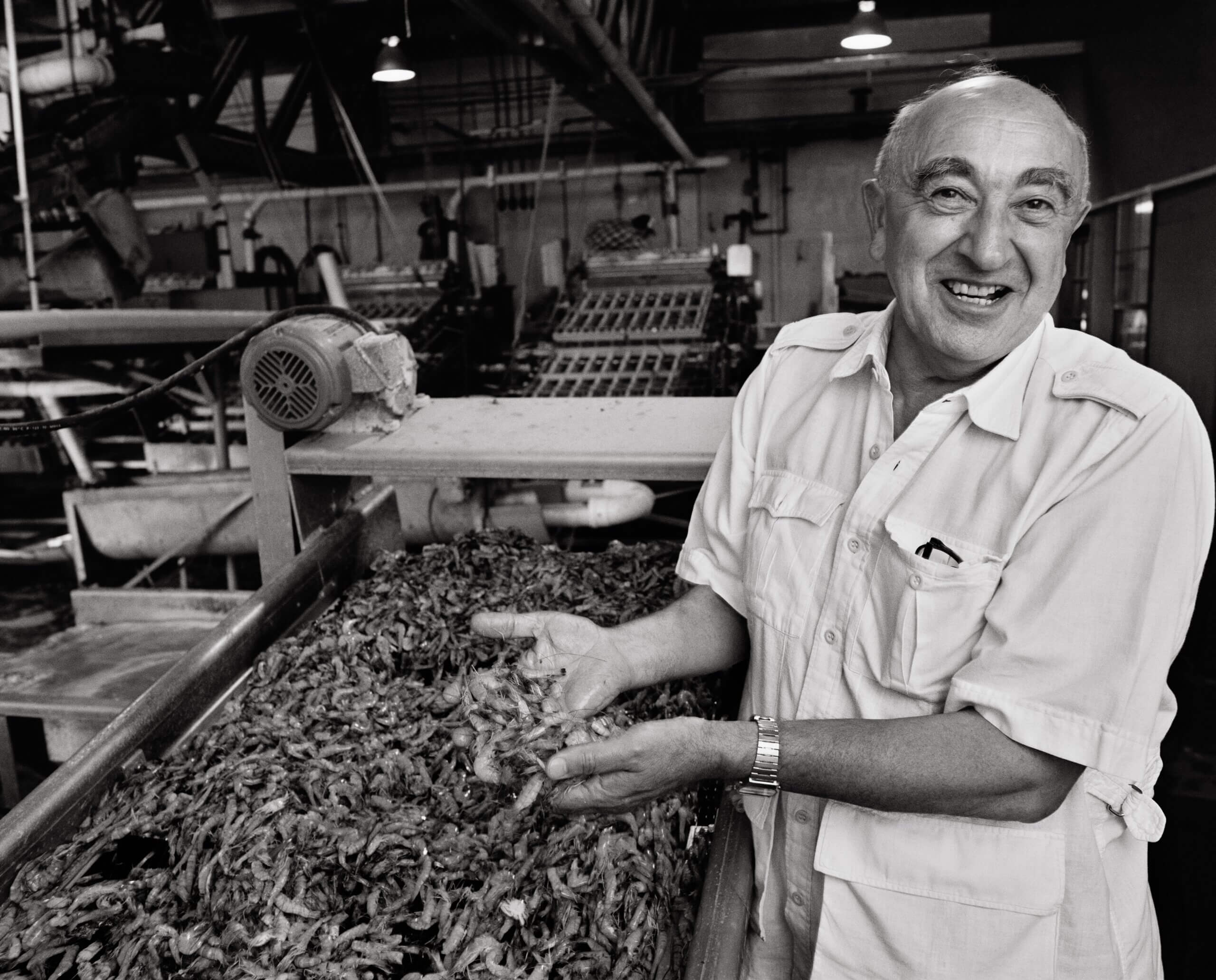

These photos are anything but passive. People smile or glower directly into the camera, and proudly present their life to the lens — a handful of shrimp from a Jewish man who built a business selling the shellfish to New Orleans restaurants, a woman showing off a bowl full of her famous chopped liver, a woman grinning as she carries a Torah on Simchat Torah. There is a clear symbiosis between Aron and his subjects, in which they each shaped and enlivened each other.

This, Aron said, was not the style of street photography at the time he came up. People were not supposed to document their own communities, nor were they supposed to engage with their subjects.

“It was frowned upon to study your own community — you were supposed to go out,” he said. “Street photography was supposed to be dispassionate.”

But of course people saw the camera and reacted to it, so he embraced that fact, spending hours talking to his subjects and learning their stories. Now that he has bequeathed his work to the AJHS, those stories are preserved not only in images but also in a podcast accompanying the exhibit, in which Aron is able to preserve the memories behind each photograph.

The stories come through in the images alone, too; each shot is redolent of Aron’s affection for his subjects. An Israeli soldier in Jerusalem’s Old City makes flirtatious eye contact with a woman as his companions smirk. An elderly man on a bench dives in to kiss his wife on the cheek. Holocaust survivors beam out from full-color photos, not reduced to the numbers on their arms but presented as “people who lived lives, lived beyond their nightmares, had families where they could, given back to their communities,” Aron said.

Not every image, on its surface, seems Jewish — there isn’t always a yarmulke or a lulav or a Torah scroll in frame. Nevertheless, Aron manages to find the sense of Jewishness that knits these images into the tapestry of Jewish life.

In a photo of a couple embracing at the liquor store they ran in Arkansas as part of the Shalom, Y’all series, Aron told me that only the husband was planning to be photographed, because his wife wasn’t Jewish. The photographer invited her anyway, and the couple ended up explaining that an Orthodox rabbi had performed their marriage ceremony. This seemed wrong to Aron — Orthodox rabbis don’t perform intermarriages — so they produced their marriage certificate to show him. As they pulled it out of the envelope, he recounted, another slip of paper fell out in which the rabbi had written that the wife had consented to become a member of the people of Israel and was now a Jew, a fact she was unaware of but delighted, Aron recalled, to discover.

“I loved interacting with people while I was photographing,” he said, “and the people became part of the portrait.” Aron did too.

The exhibit The World in Front of Me is showing now through June 4 at the American Jewish Historical Society.