Return of the European Jew

Being Jewish in the New Germany

By Jeffrey M. Peck

Rutgers University Press, 224 pages, $24.95.

Turning the Kaleidoscope: Perspectives on European Jewry

Edited by Sandra Lustig and Ian Leveson

Berghahn Books, 288 pages, $80.

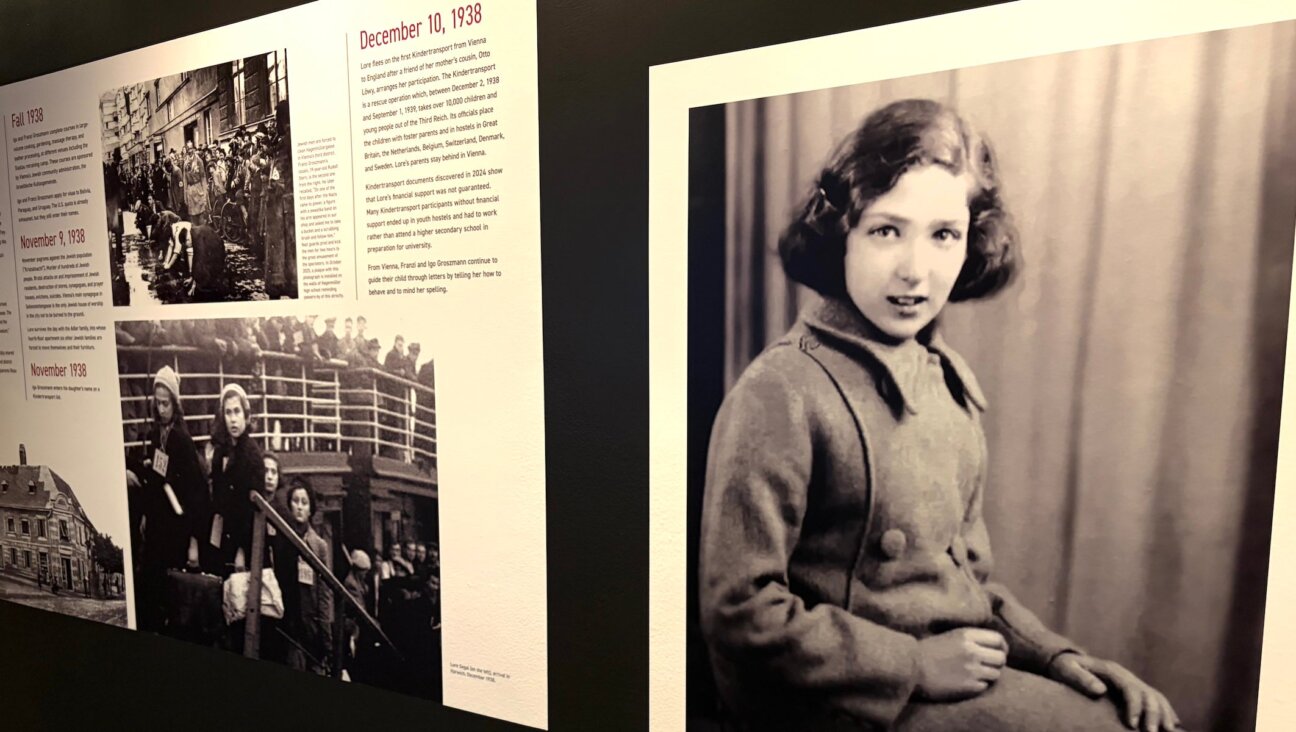

In 1946, Robert Welsch, a German Jewish journalist who had fled to Palestine during World War II, went back to Berlin. “It smells of corpses here, of gas chambers and torture chambers,” he wrote. “The remnant of Jewish settlements in Germany must be liquidated as quickly as possible. Germany is no soil for Jews.”

After World War II, it indeed seemed as though the future of Jewish life was in America and Israel. European communities were merely refugee centers that would eventually fade away. But over the following years, Jewish life in Europe hung on and then recently began to expand. Today, the country with the fastest-growing Jewish population is, of all places, Germany — and Jewish communities are strengthening on both sides of the former Iron Curtain. As two recently published books suggest, the new vitality of these communities has led to an insistence on a uniquely European Jewish identity: the idea that European Jewry can be a “third pillar” or an alternative to American and Israeli models of Judaism.

In the search for answers to how this came about, Jeffrey Peck, author of “Being Jewish in the New Germany,” points to two key factors: the end of the Cold War, and the emergence of the European Union. When communism fell, Soviet Jews headed west — particularly to Germany, where new immigration laws gave special privileges to Eastern Europeans of Jewish origin. Many of these Jews could have gone to Israel. Instead they chose Germany, Peck explains, for its more familiar European culture, its powerful economy and its security relative to the conflict-ridden Middle East.

And while Jewish communities with slowing birthrates in the West were energized by immigration, the birth of the E.U. led to closer ties between Jews of various nations of Europe who were once isolated from each other. These included members of tiny Jewish communities in former East Bloc countries, now free to practice their religion openly.

Peck shows that the New Europe is rife with contradictions. On the one hand, Jews have criticized the E.U. for its pro-Palestinian politics. On the other, the E.U. is Israel’s leading trade partner. In Germany, Israel’s biggest supporters are members of the Green Party, on the far left of the political spectrum. In Italy, Israel’s supporters are Berlusconi-voting conservatives, all the way on the right. Europe has recently seen a rise in antisemitic acts and in criticism of Israel, but the new E.U. constitution outlaws discrimination throughout the continent. Birthrates and Jewish marriages are going down, but Jewish activity (admittedly sometimes by non-Jews) has gone up.

After giving an overview of the facts on the ground, Peck speculates that contemporary European Jewry can transform Judaism to be more inclusive, which he feels is all the better. He dismisses complaints that events such as Jewish cultural festivals, open to Jews and non-Jews alike, don’t count as genuinely Jewish. “Just as branding an automobile as ‘made in America,’ though parts are imported from around the world and assembled by immigrant labor, a state of pure “Jewishness” is no longer possible to achieve….” (It should come as no surprise that Peck is the kind of guy for whom eating lox and bagels qualifies as a Jewish experience — a claim he makes in the book.)

Several of the contributors to the anthology “Turning the Kaleidoscope: Perspectives on European Jewry,” edited by Ian Leveson and Sandra Lustig, take a similarly optimistic view. Lars Dencik, a Swedish professor of social psychology, agrees with Peck’s expansive model of Jewish identity. He cites surveys showing that Jews in Sweden identify strongly as both Swedes and Jews — not one or the other, but fully both at once. Swedish Jews pick and choose from both Swedish and Jewish traditions in what he calls a “postmodern Swedish smorgasbord Judaism.”

Another possibility for European Jewry, suggested by British contributor Clive Lawton, is that they “can mediate the gap” between America and Israel the way England has between America and the E.U. He contrasts the American model of Jewish identity, which is based on one’s private relationship with faith, to its opposite extreme, the secular Israeli model, in which Jewish identity is nationalized and has almost no religious component. Lawton posits the existence of a European identity model that falls somewhere in the middle of these two extremes and is about “community.” Though Lawton is a bit vague on the particulars of what this might mean, he suggests that it involves a pragmatic consensus approach to problem solving on a local level.

Indeed, as other writers in the anthology point out, pragmatism and flexibility are the key words of the day for European Jews, as women are being counted in minyans in Norway and alternative communities have developed in the shadow of traditional Orthodox communities in Amsterdam, Vienna and Berlin.

However, not everyone is so sanguine. Goran Rosenberg, a Stockholm native and the child of two Polish survivors from Auschwitz who moved to Sweden after the war, claims that the Holocaust and Israel defined Jewish existence after World War II. As these influences fade, he argues, so, too, must Jewish identity, especially if there’s nothing concrete to replace it with. “If ‘Jew’ can mean anything,” he writes, “logic demands that Jews cannot be expected to think and act in any particular way.”

Similarly, the anthology’s editors warn that defining Jewish identity in terms of menorahs, bagels and klezmer makes it into an all too easily packaged commodity, when, in fact, Judaism is much more complex. Universalizing the Jewish story also has more serious repercussions. Leveson and Lustig remind us that when remembering the past, “Jews and non-Jews commemorate different things: Jews commemorate their own concrete persecution…. Non-Jews… commemorate their responsibility.” Yet in the contemporary European narrative, everyone’s a victim of the Holocaust, which becomes “a romanticized horror suffered jointly by Germans and Jews.”

Maybe it is possible that European Jewry can act as a “third pillar” of the Jewish world. The question, however, is what specifically does that “third pillar” represent? What do European Jews want, and how can they achieve it in a climate that is both welcoming and hostile? In the end, for all their intriguing perspectives, neither of these two books presents aentirely completely convincing answer to the questions above. But the simple fact of their existence — of the questions posed and theories offered — is a hopeful sign of the tantalizing possibilities for the future of Jewish life in Europe.

Aaron Hamburger is the author of ‘The View From Stalin’s Head’ (Random House) and the novel ‘Faith for Beginners,’ which was released this month in paperback by Random House.