How Henryk Ross’s Amazing Photos Unearthed The History Of Lodz — And Mine As Well

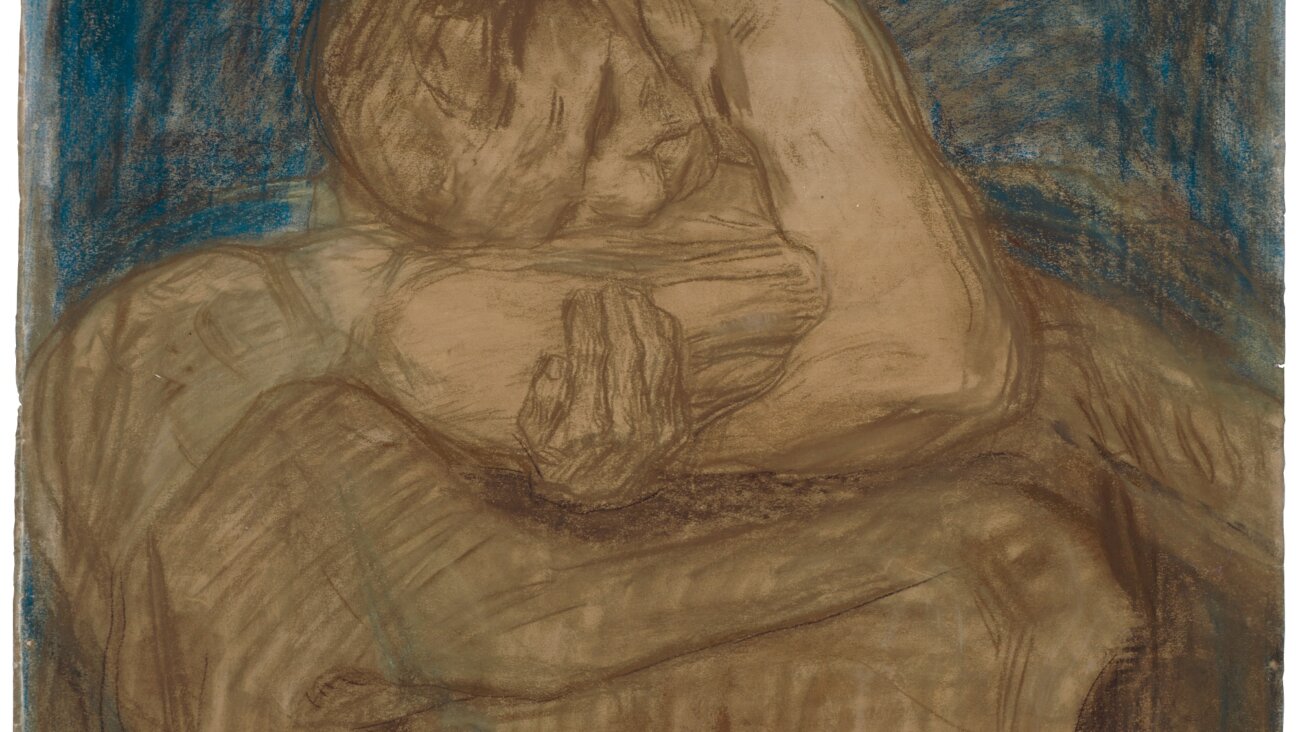

Memory Unearthed: The Lodz Ghetto Photographs of Henryk Ross

At the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through July 30

The story of the Lodz Ghetto has become folkloric. Chronicled in novels such as Leslie Epstein’s “King of the Jews” and Steve Sem-Sandberg’s “The Emperor of Lies,” this was the place that the dictatorial Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, the so-called Elder of the Jews, transformed into a giant slave-labor factory for the Nazi war machine. Because of its productivity, Lodz, in German-occupied Poland, was the last Jewish ghetto to be liquidated, with the final deportations occurring in August 1944. But, in the end, even Rumkowski was sent to his death at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Rumkowski’s portrait is prominent in the surviving images of Henryk Ross, an official — and unofficial — ghetto photographer. Ross (1910-91) was tasked by Jewish authorities with creating identity cards and propaganda photographs of the Lodz workshops. But he also risked his life to show the hunger, shabbiness and misery of the ghetto, as well as families torn apart by deportations to Chelmno and Auschwitz. One of fewer than 900 Jews left behind in Lodz at war’s end, he was liberated by the Soviet Army in January 1945 and, in March, recovered his buried photos. He settled with his wife, Stefania, in Israel, where he testified at the 1961 Adolf Eichmann trial.

“Memory Unearthed: The Lodz Ghetto Photographs of Henryk Ross,” an exhibition organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario in association with Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, is both a testament to his courage and a remembrance of the tens of thousands of Jews imprisoned in the ghetto during World War II. (It’s worth noting, as Ross does in documentary footage, that his wife was an indispensable partner in his photographic enterprise.)

A somber voyage through the ruins of Jewish communal life, the exhibition had special resonance for me. I saw it in the company of a long-lost cousin, Peter Coleman, whom I met for the first time last December – and who told me that our family had immigrated here from Lodz.

Peter’s father, Charlie, was the elder brother of my maternal grandmother, Betty. With two other sisters, Aida and Mae, and my great-grandmother Anna, they reached New York on July 8, 1907, on the SS Barbarossa. It is likely that my great-grandfather, Samuel Cohen, who did not travel with them, was already here. The family’s youngest child, my great-aunt Rae, was born in New York in June 1908.

As part of the great pre-World War I migration of Eastern European Jews, we fled poverty and pogroms. We may well have left cousins behind, in Lodz or elsewhere. I know little for sure. My maternal grandfather, who emigrated from present-day Belarus on his own at age 14, exchanged letters in the 1950s, in Yiddish and Russian, with a cousin in Dagestan, in the Soviet Union. The cousin writes that he and his sister Rebecca were the only close family members to have survived. An aunt told me that my father’s mother, Grandma Ida, had lost a brother in the Holocaust. But my knowledge of my extended family’s fate, like that of many American Jews, is frustratingly sketchy.

Until Peter and I connected, I had no idea that this branch of my family had once called Lodz home. That first generation never talked about the old country, at least not to us. In fact, my grandmother Betty, 5 years old when she emigrated, always claimed to have been born here. Unlike my other three grandparents, she spoke without a foreign accent and wrote beautiful English.

After my mother, who had been an only child, died in 2009, I reached out to her first cousins, all still alive at the time. But none of those I found had been in contact, for decades, with Charlie’s two children, Peter and Janet, whose family had changed their name to Coleman (from Cohen) and seemingly disappeared.

There were tantalizing clues about family rifts: My grandmother, in her letters from 1950, expressed anger at her brother over a loan she had made to him, and my mother, in a deathbed interview, said that Charlie’s mother, Anna, and his wife, Dorothy, had never gotten along.

An engraved invitation to Peter’s wedding to his first wife, at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Beth Sholom synagogue in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, turned up in my grandmother’s correspondence. The marriage had been brief, Peter’s ex-brother-in-law, Joel, told me and he was no longer in touch with my cousin. But he remembered that Peter was a biochemist or physicist who’d met Joel’s sister at Columbia University and had taught at Harvard. But inquiries to both universities turned up nothing.

Last summer, to my delight, Peter, now 79, found me. I owe our reunion to Peter’s current wife, Jane, who had told him she wanted just one thing for her birthday: to know some of his father’s family. Peter managed to track down another cousin, Paul, to whom he’d last spoken in 1992, when Aunt Mae died. Paul put us in touch.

During our emotional first meeting in New York, Peter, a retired professor of biochemistry at New York University filled in missing details of our family history.

The name change to Coleman, in 1944 or ’45, was a response, he said, to anti-Semitism that his father believed had kept him from finding work as an electrician. And his father’s quarrel with my grandmother had “everything to do with money” – specifically, a loan she had made to help his family buy a house in Teaneck, N.J. At some point, for reasons unknown, my grandmother called in the loan, and the Colemans were obliged to sell their suburban home and move back to the Bronx, disrupting their lives. But Peter, a talented musician and artist before he became a scientist, had nonetheless flourished, as had his younger sister, Janet, a historian of political theory who had settled in England.

After we saw the Lodz show, I asked Peter and Jane for their reactions. “I keep thinking,” he said, “that if the family didn’t get here, of course, I’d be smoke. None of us would be talking.” He expressed surprise, too, “that there were so many smiling faces, so many photographs of what seemed to be normalcy in the most abnormal, grotesque situations imaginable.

“These people were ghettoized: they knew that they were being herded like animals…Yet you see people smiling into the cameras. You say to yourself, ‘What are you so happy about?’ Of course, they’re looking at things through a very colored lens – they have a life they have to live.”

I said I was particularly struck by Ross’s daring. By surreptitiously photographing the deportations — the children crammed into horse-drawn carts, the adults being herded into a rail car — he put himself in grave danger of joining them. And he did all this knowing that his photographs, which he buried for safekeeping, might never see the light of day.

“I think, psychologically, there’s a comfort,” Peter’s wife, Jane told me. “Like putting a message in a time capsule. It at least keeps hope alive.” It was supremely lucky, it seemed to me, that Ross had lived to retrieve his photos, that roughly half his 6,000 negatives had survived — and that the Colemans and I had managed, so many decades later, to examine Ross’s time capsule together.

Julia M. Klein is the Forward’s contributing book critic. Follow her on Twitter, @JuliaMKlein

A message from our editor-in-chief Jodi Rudoren

We're building on 127 years of independent journalism to help you develop deeper connections to what it means to be Jewish today.

With so much at stake for the Jewish people right now — war, rising antisemitism, a high-stakes U.S. presidential election — American Jews depend on the Forward's perspective, integrity and courage.

— Jodi Rudoren, Editor-in-Chief