In 1930s German And Austrian Art, Portents Of A Dark Future

A. Paul Weber (1893-1980) Frontispiece illustration for “Hitler: A German Doom,” 1931-32 Image by © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Currently at the Neue Galerie, the exhibition “Before the Fall: German and Austrian Art of 1930s,” is as fateful as its title suggests — devoted to paintings, photographs, prints and drawings made under the lengthening shadow of Nazi terror.

It’s a show suffused with anxiety and denial. Many of the artists were representatives of the so-called “New Objectivity,” a post- and anti- Expressionist movement that attempted to unmask ordinary social reality. Every image can be read in the foreknowledge of what lay in store for these artists, for Europe, and the world. On loan from the Museum of Modern Art, the surrealist Richard Oeize’s “Expectation” (1935-36) a large monochromatic painting of urban types, backs turned to the viewer as they mass in the countryside beneath a lowering apocalyptic sky, may have been motivated by the artist’s personal psychology but history has given it another meaning.

Thus overdetermined, “Before the Fall,” curated by the German art historian Olaf Peters, resembles “L’Art en Guerre: France 1938-1947” the vast exhibition of work produced in exile or under occupation mounted five years ago at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris. (The surrealist painter Max Ernst has the distinction of appearing in that show as well as this one). But while the artists in the French exhibit were creating mid cultural cave-in, those in “Before the Fall” are more like canaries in the coal mine.

Woodland landscapes are charged with foreboding, if not always as openly as in Rudolf Schlicter’s “Devil in the Forest” (ca. 1933). Something is rotting. Cities are danger zones. The most succinct example may be Rudolf Dischingers’s 1935 “Threat,” a painting of a faceless mannequin relaxing in an empty room, oblivious to the giant robot-like figure lurking in the window. Although less overtly ominous, Dischinger’s 1934 placid “Suburban Street” notably is dominated by an outsized police officer. Dischinger’s mentor Karl Hubbuch, an anti-fascist who would be forbidden by the Nazis to paint, is represented by a disquietingly pastel-colored urban scene of monstrous school kids, “Children Growing Up Under Stones” (1934).

The show’s most renowned painters — Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, and Oskar Kokoschka, as well as Max Ernst — were all included in the Nazi’s notorious 1937 Degenerate Art Exhibition. “Before the Fall” also has an abundance of the photographer August Sander’s taxonomic portraits, also banned by the Nazis. One of the show’s discoveries, Wilhem Traeger’s fierce expressionist linocuts of 1932 Vienna, made when he was 25, occupy a wall opposite one belonging to Beckmann. Had Traeger been better known he might also have been considered an enemy of the state. Just as Traeger subtly superimposes a skeleton over a uniformed soldier, another linocut street scene, with its grim graffiti-scrawled wall, barbwire and beggars, seems a flash-forward to a Nazi-created ghetto.

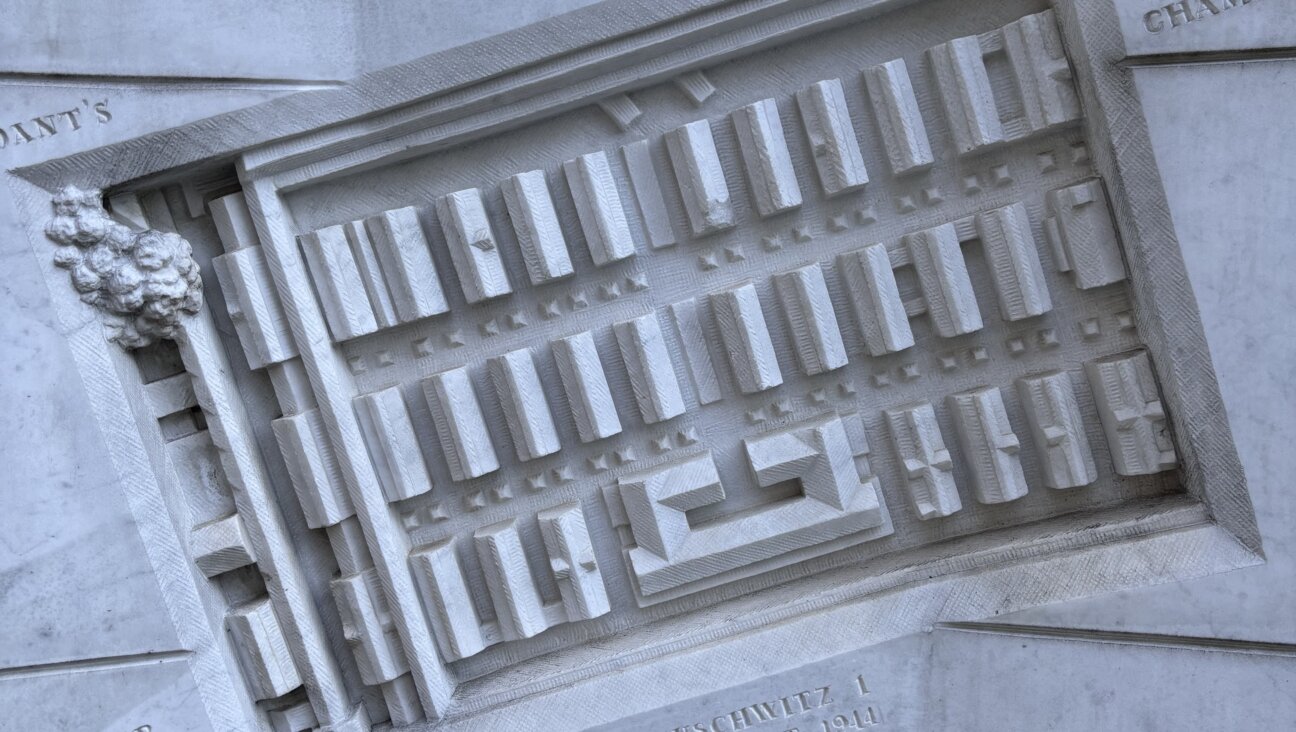

“Before the Fall” includes many lesser known artists but relatively few Jewish ones. With the exceptions of the photographers Erwin Blumenfeld and Helmut Lerski, both of whom managed to escape Germany, Jews can be identified by their death dates: The painters Felix Nussbaum and Friedl Dickerson-Brandeis were both murdered at Auschwitz in 1944. Perhaps Ottilie Cieluszek, whose dates are unknown, perished there as well. The Austrian painter Rudolf Wacker, a talented precursor of a subtly macabre magic realism, died in 1939 after being brutally interrogated by the Gestapo — not a Jew but openly anti-Nazi.

It’s a haunting exhibit. In fact, it’s doubly haunted (at least for me) in that beneath the museum’s posh façade I can still see traces of the Beaux Arts mansion’s previous, somewhat shabbier tenant — the Yiddish Scientific Institute (YIVO) where, as a grad student in the late 1970s, I held a work-study job.

I came in a few days a week and was mainly involved in making a slide show based on the photographs in “Image Before My Eyes,” a YIVO-Jewish Museum exhibition on pre-World War II Polish-Jewish life. If the job sounds laughably low tech, it was not regarded as so by the folks at YIVO. As an American boy in a world of Polish refugees, I was not infrequently called upon to use my mechanical expertise in other ways, such as changing a light bulb.

For me, YIVO was a living museum. Some staffers arrived from Poland in the decade following World War II, others more recently, following the 1968 purge of Poland’s Jewish communists. One such presided over the main room that served as an office for a half dozen or more archivists and now is dominated by the Neue’s chef d’oeuvre, Gustav Klimt’s gold-on-gold portrait of Adele Bauer-Bloch. It was said that she had been an important Polish Workers’ Party functionary. What impressed me then was her interest in the Wall Street Journal which she seemed to read religiously, clipping key articles. Was she a born-again capitalist or an evidence-gathering red?

Off the main room was the library, a gallery now largely devoted to Jugendstil ceramics and other chachkas. This was the domain of Dina Abramowicz, a tiny woman with thick glasses who was herself something of a sacred relic, having been employed at the original YIVO in Vilna and survived the liquidation of the Vilna Ghetto, making her way to New York where she worked with Max Weinrich to recreate the institute.

The library was a secular beit midrash, home to a crew of seemingly permanent researchers. It was not easily navigated by outsiders. A Yiddishist told me that a visiting Israeli scholar was so frustrated by the unwritten rules of the YIVO library that she was driven to suicide. Who knows? YIVO humor skewed dark. (It was the first place that I heard the pun, “there’s no business like Shoah business.”) I can’t say that I ever went native but I absorbed enough during my time there to know, once I began researching “Bridge of Light,” my book on Yiddish cinema, that call slips filled out in Yiddish — including one’s name — were likely to get more prompt attention.

The third floor was a maze of small private or semi-private offices for individual sages. Lucjan Dobroszycki, the chief curator for “Image Before My Eyes” and my nominal supervisor, occupied one of these, squeezed in among stacks of manuscripts and photographs. “Doctor D,” as he was known, was both kindly and sardonic. I once asked him if there were any pictures of my grandmother’s home town, Maków. He produced a photo of a tumbledown houses on an unpaved street complete with fetid stream of muddy water. “That’s Madison Avenue,” he said, then handed me one even worse. “This is Fifth.”

Most of “Before the Fall” is installed on the Neue’s third floor. One gallery — so small that it can really accommodate only a half dozen people at a time — recalls the archival density of the mansion’s previous incarnation.

The gallery’s most eye-catching work is Felix Nussbaum’s accomplished, accusatory “Self-Portrait in the Camp” (1940), a painting that is hung to meet the viewer’s gaze with its own and which although somewhat tucked away has become the exhibit’s signature piece. Also given pride of place, on its own wall opposite the entrance, is Friedl Dicker-Brandeis’s painting, “The Interrogation II” (dated 1934-38). This raw, paint-clotted semi-abstraction makes a startling contrast to the fastidious pedagogical photo-montages for which she may be better known.

These canvases are embedded in context. The walls have a double row composed of Nazi propaganda posters, ferocious political cartoons by the “National Bolshevik” A. Paul Weber (anti-Nazi but also anti-Semitic), terrific anti-Nazi drawings by Alfred Kubin (another “degenerate artist”), grim World War I images by Wilhelm Sauter (an artist favored by the Nazis), Erwin Blumenfeld’s well-known bloody Hitler portrait, the émigré Erika Giovanna Klien’s pastel “Street Battle” (1930), and the mysterious Ottilie Cieluszek’s anti-Nazi cartoons, one of which “Deployment” (ca. 1933) is a purposely childlike rendition of a Nazi victory parade.

It’s as if the whole of the exhibit were concentrated in one claustrophobic space. Showcasing doomed artists, crammed with fragile artifacts charged with a desperate passion, the room gave me the uncanny sense that the Neue Galerie was exhibiting YIVO itself.

- J. Hoberman is the co-author, with Jeffrey Shandler, of Entertaining America: Jews, Movies, and Broadcasting. He spent 33 years reviewing films for The Village Voice and was, in the 1990s, an intermittent theater critic for The Forward.*

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO