For An Art Rebel, Martha Rosler Proves Surprisingly Orthodox

Point ‘n’ Shoot: Martha Rosler targets the president in her recent work. Image by The Jewish Museum

I’m not sure what to make of the title of the Martha Rosler retrospective at the Jewish Museum, “Irrespective.” According to the wall text, it’s supposed to be a portmanteau, “a clever play on terms that lie somewhere between the words ‘retrospective’ and ‘irreverent.’” The exhibition, we’re promised, will be no mere shrine to its subject. Instead, Rosler offers us something cheekier and more conceptually challenging, dancing nimbly around museum conventions.

Rosler, who has been called one of the most influential American artists of the past 40 years, attended yeshiva in 1950s Brooklyn. By her own account, she gravitated to feminist critical theory partly as a way of rebelling against the restrictive gender norms of Orthodox Judaism. But, in distancing herself from the religion of her adolescence, she seems to have, ironically, converted to an inflexible sect of conceptual art, which, in its allergy to aesthetic pleasure and its privileging of word over image, sounds suspiciously like the thing she thought she was fleeing.

An air of adoration wafts through the supposedly irreverent “Irrespective.” It’s there in the semi-worshipful “Reading Hannah Arendt (Politically, for an Artist in the 21st Century),” a series of transparent panels decked out in quotes from the political philosopher, and in “Off the Shelf,” a series of chromogenic reproductions of her favorite books, including titles by Adorno, Benjamin and Chomsky. Rosler’s familiarity with these thinkers probably made her an excellent professor (she taught at Rutgers for 30 years); whether they helped her make good art it less clear. Too often, her pieces come across as advertisements for political perspectives we’re meant to accept without any real hesitation.

Her earliest major work, “The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems (1974–5),” arrived at a time when gentrification was slowly beginning to transform Manhattan’s Skid Row into a hipster inferno. Spoiled kids with fancy cameras would shoot winos lying on the sidewalk and then pass off the results as high art, a practice that detractors called the “find-a-bum school.” Tired of the phony romanticism of street photography, Rosler offered an interpretation of New York that featured 21 black-and-white photos of local storefronts, 24 text panels listing slang words for drunkenness but zero New Yorkers. The images — derelict, shadowy and calculatedly empty — pack an undeniable punch. Paired with words, they verge on apocalyptic, as if post-Watergate America is crumbling under the weight of its prejudices.

Encountering “The Bowery” for the first time in college, I admired Rosler for throwing out the rulebook. Seeing the piece again at the Jewish Museum, I wondered if she’d thrown out the baby with the bathwater. Nobody can deny that photographers have taken exploitative pictures of marginalized people. But to give up on representing the body altogether — at a time when the municipal government had largely given up on Manhattan’s homeless — seems like a tactical error, ceding valuable aesthetic territory to the find-a-bummers. “The Bowery” may be Rosler’s most influential work; it also may be her most harmful. Without meaning to, she inspired a generation of adventurous, politically minded photographers to retreat from the messiness of human interaction in favor of clever-clever formalist conceits that, as time went on, seemed to say less and less about the world at large.

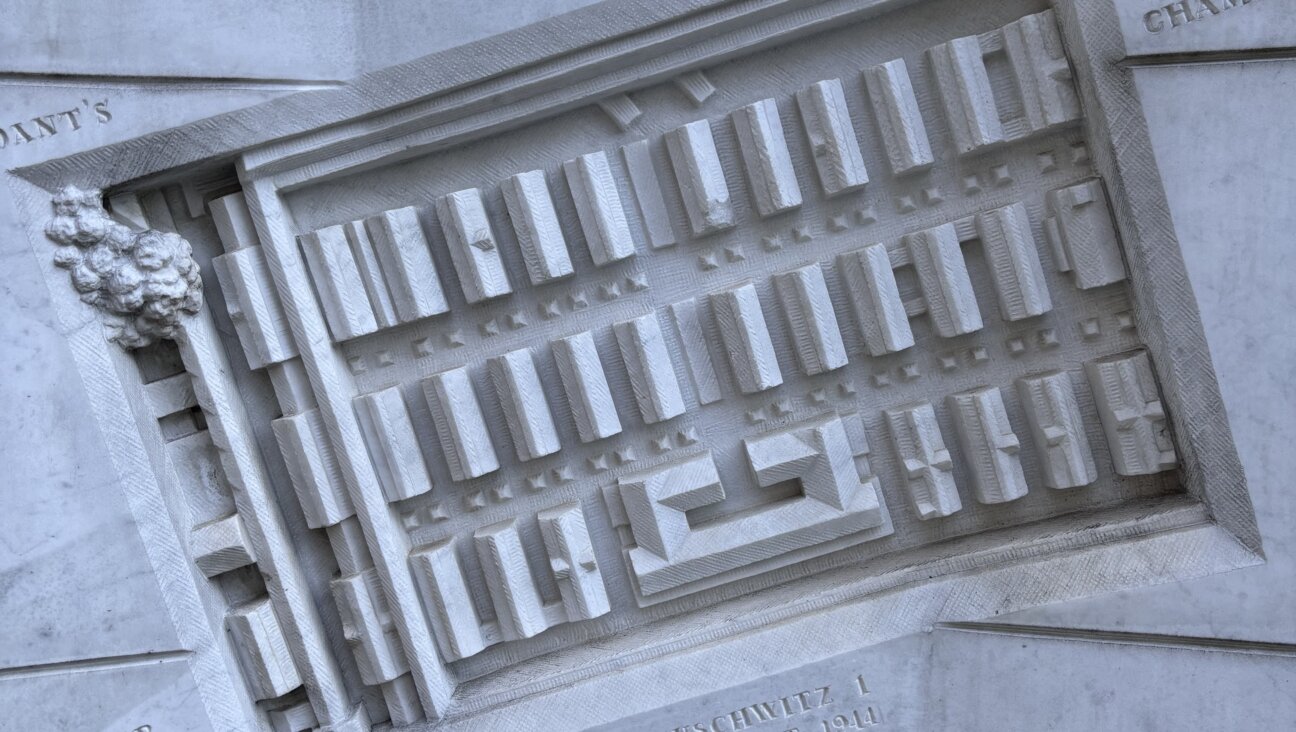

Vital Statistics: A still from Martha Rosler’s “Irrespective” exhibit at the Jewish Museum. Image by The Jewish Museum

Whatever its influence on American art, “The Bowery” remains poignant and provocative. In no small part, that’s due to the complex beauty of Rosler’s photography. As the piece’s title suggests, images of stores and sidewalks and empty bottles may not add up to any genuine description of the Bowery, but they always seem to be striving to say something, only to be undermined by the stack of words to the right or the left. In “Semiotics of the Kitchen” (1975), Rosler’s next major work, there’s no longer tension between words and images — words have won. In a blurry, six-minute video, Rosler plays the part of a cooking show host, reciting a sardonic version of the alphabet that hints at barely concealed rage. It’s interesting to compare “Semiotics” with another 1975 film, Chantal Akerman’s “Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles.” Akerman and Rosler are interested in many of the same themes — female domesticity, food as labor, violence as liberation. But Akerman explored those themes through nuanced camerawork and shots that get more mesmerizing the longer you ponder them. By contrast, the images seem almost incidental in Rosler’s film; they have no style or intrinsic beauty, and that’s why it can be hard to watch “Semiotics” more than once, or even once all the way through.

Too many of the pieces in “Irrespective” are aesthetically bland and politically undercooked: You keep jumping back and forth between politics and aesthetics, trying in vain to get to the crux of the issue. I admire Rosler for making art about the persecution of Ethel Rosenberg, but I’m skeptical that “Unknown Secrets (The Secret of the Rosenbergs)” (1988) succeeds as portraiture, canonization, activism, journalism, agitprop or anything else. No doubt Rosenberg intrigued Rosler because her story evokes domesticity, U.S. nationalism and anti-Semitism. But the piece (at least in its pictorial half) doesn’t imply anything especially interesting about these subjects; they just sit there, unmixed and unexamined, like the photographic reproductions that border the central figure.

And so, like a bored symphony patron rifling through the playbill, you turn to “The Secret of the Rosenbergs,” the 15-page essay that Rosler wrote to accompany her photomontage. The writing is incisive and well-researched, though not a patch on Howard Zinn or Joyce and Gabriel Kolko’s takes on the same subject. Forget the painted word (Tom Wolfe’s slur for overly cerebral, abstract art) — Rosler offers the word, plain and simple.

One sentence from “The Secret of the Rosenbergs” jumps out: “Today the terrorist,’ yesterday the ‘Atom Spy.’” The year Rosler wrote this, George H.W. Bush was elected president of the United States. Before his first term was over, he’d sent troops into Kuwait. Twelve years after that, Bush’s son got the same job and quickly set out to invade Iraq and Afghanistan, promising to protect his people from terrorists threatening to destroy the American way of life forever. You could say the links between those last few sentences are tenuous, but I think they’re exactly the kinds of connections Rosler is inviting her audiences to make. American history, as she sees it, is a power struggle in which the haves try to terrify the have-nots into submission with stories of spies and terrorists and caravans.

Part of the difficulty I have with Rosler’s political art is that I’m tempted to agree with her premises. But I also worry that her pronouncements come too easily: They ignore the humdrum of actual politics, glossing over difference for the sake of simplicity.

From Martha Rosler’s “Irrespective”: “Frankfurt, Untitled.” Image by The Jewish Museum

One risk of interpreting American history as an age-old power struggle is that you may come to accept that this struggle never ends. If you can’t be bothered to look closely enough to find the differences between the past and the present, then the present starts to feel as inevitable as the past. A thin line separates the analogy between the Iraq and Vietnam wars from the soothing mantra that Iraq is just another Vietnam. This occurred to me while I was roaming through “Reading Hannah Arendt,” the piece Rosler completed in 2006 for the 100th anniversary of Arendt’s birth, apparently in the confidence that her analysis is as relevant to the War on Terror as it was to totalitarianism. I paused in front of a quote from “On Violence”: “The greatest enemy of authority… is contempt, and the surest way to undermine it is laughter.”

I haven’t read all of Arendt, but I’m not sure a more dated sentence could be found in her oeuvre. Every time Jon Stewart made fun of Bush Jr.’s dyslexia, Republicans cheered — for what better proof could there have been that liberals were a pack of grammar snobs? Since the W days, we’ve seen hard-line politicians embarrass themselves badly enough to make the whole country chortle, only to shoot up in the polls. Disgraced stars are always showing up on “Saturday Night Live” to make fun of themselves, because they know that self-mockery is one of the surest ways to the public’s heart. One such star, in case you forgot, is the current commander in chief.

Rosler probably hasn’t forgotten, because two of the most recent pieces in “Irrespective” take as a subject Trump’s rise to power. The more striking of the two is a short compilation of news clips from his early Cabinet meetings. As the video proceeds, red X’s appear over the heads of those who have since been fired, and their voices rise to munchkin octaves.

Museum patrons seem to find the video funny. I’ll admit that I laughed, too, though the piece clarified what I find frustratingly absent from Rosler’s career. Recently there’s been a lot of disagreement over the right and wrong ways to make political satire, but I submit that the one thing Trump-era satire should not be is complacent: It should not put viewers in the smug position of knowing what happens next, of knowing who gets fired and who sticks around. The tone of Rosler’s video seems better suited for the tyrants Arendt was writing about, the kind who depended on seriousness and on pomp and circumstance instead of constantly sabotaging them. What, I wondered, was Rosler doing with this news footage that the footage didn’t already do to itself? High voices are funny, but aren’t the things Mike Pence and Ben Carson and Rex Tillerson are saying funny enough to begin with? Are people going to change their minds about the Trump administration after watching this video?

Does “Irrelevant” sound too harsh?

Jackson Arn is a New York-based journalist and critic.

‘Martha Rosler: Irrespective’** *runs through March 3, 2019 at the Jewish Museum in New York.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO