So much to say about Israeli violence, so little to say about violence against Jews

Pankaj Mishra’s ‘The World After Gaza: A History’ offers a reading of current events that is more political and personal than historical

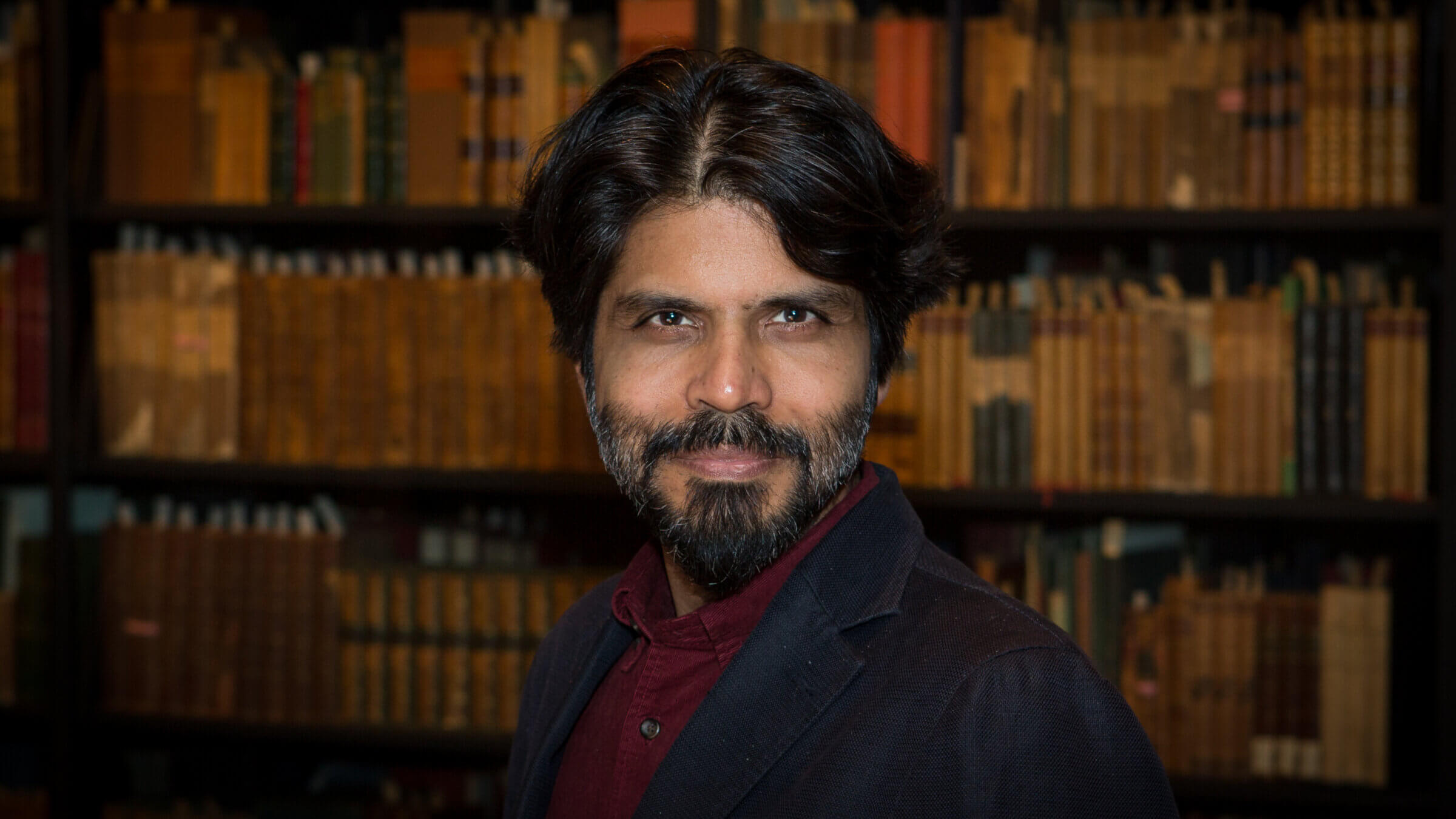

Pankaj Mishra’s latest book is ‘The World After Gaza: A History.’ Courtesy of Pankajmishra.com

The World After Gaza: A History

By Pankaj Mishra

Penguin Random House, $28, 304 pages

The title of Pankaj Mishra’s new book, The World After Gaza: A History, is compelling for those who are paying attention to the lives of those living in this tortured strip of land. In the face of a seemingly interminable tragedy, the title promises a glimpse of an end. And, though Mishra offers little hope, he also refuses despair. If the past is prologue to the present, this seems about right.

But the title is, at times, also misleading given the way Mishra presents this particular and knotted past. He has given us a work that is less historical than personal and often polemical. The work, moreover, is less about the world after Gaza than the world still in the midst of Gaza. We must never lose sight, or let others lose sight of the act of unspeakable inhumanity committed by Hamas on Oct. 7. At the same time, though, we must never allow ourselves to lose sight of the ongoing act of equal inhumanity by the IDF that seems to have no end in sight. Perhaps it is too early to write a history, much less imagine a future.

The author of several nonfiction books, as well as a frequent contributor to The New Yorker and New York Review of Books, Mishra has done due diligence for this history, amply attested to by the works he cites in the text, as well as those listed in the bibliography. He has read not just older and traditional accounts of the history of Israel and Gaza, but also more recent and revisionist narratives.

Yet the editorial team at Penguin has done the reader a serious disservice by providing neither footnotes nor index to a work that presents itself as a history of Gaza. Though I am an academic (albeit French) historian, this is not a scholastic quibble. Even when professional historians cheapen these practices to parade their erudition, footnotes also allow readers to check the veracity of the interpretation. As a result, whenever Mishra made a claim I found a bit odd or a bit sweeping, I had to scramble to check if, in fact, it was textually or historically grounded.

For example, Mishra states that John Dower, author of War Without Mercy, his stunning account of the racial and racist character to the war in the Pacific, reveals how Japan’s aggression “stirred the deepest recesses of white supremacism and provoked a response bordering on the apocalyptic.” Yet Mishra neglects to mention that Dower also notes that the Japanese responded in kind — only that their racist tracts were “frequently more witty and artistically sophisticated.” Moreover, our debasing of others was not limited to enemies in the Pacific theater; the depiction of German soldiers by Allied propaganda in both world wars was no less racist and dehumanizing.

This omission becomes more telling when Mishra presents the Yale scholar Timothy Snyder as an “anti-Communist historian” who depicts western nations as “permanently ranged against totalitarian and authoritarian enemies.” This observation reflects Mishra’s core argument, valid and vital, that western democracies have been painfully slow to acknowledge the genocidal crimes they have committed against non-western peoples.

But this description is also baffling, even disturbing. In part, this is because — perhaps this is my failing — I find the work of pro-communist historians, with the exception of Eric Hobsbawn, mostly unreadable and undependable. But it is also baffling because Snyder has written not just on the nature of totalitarianism, but has also published several essential books on nation-building in East Europe. This is also no small matter given the efforts by Putin’s Russia to reverse this process and recolonize Ukraine.

Ironically, Snyder approvingly cited Frantz Fanon, author of one of the seminal works on the colonizer and colonized, The Wretched of the Earth, in a recent essay on Putin’s drive to recolonize East Europe. (No less ironic, Snyder was the student and close collaborator of historian Tony Judt, the late historian of modern Europe whose work Mishra clearly admires.)

There are many other sins of omission and commission in the book. There is Mishra’s lamentation over the “fate” of one of “America’s oldest magazines,” The Atlantic, now led by an editor “who served in the IDF.” To illustrate the bias of the editor, Jeffrey Goldberg, Mishra cites an article by Graeme Wood “casting doubt on the number of people killed in Gaza by Israel and claiming that it is ‘possible to kill children legally.’” On the one hand, this article did, in fact, spark a storm of criticism, much of it justifiable. Wood was, strictly speaking, right; international laws of warfare do allow the killing of civilians, young and old, if the target has military value. But his numbingly narrow reading of the law ignores another and greater law: the principle of proportionality, one that the IDF has tailored to its military aims.

On the other hand, though, the Atlantic has published several scathing pieces on the lawlessness of the Israeli government and the lunacy of the extreme right. Some of the many examples include Gershon Gorenberg’s account of growing impunity of settlers in the West Bank who are expanding their presence by terrorizing Palestinian farmers, who are then evicted by government officials and Arash Azizi’s defense of the International Criminal Court’s decision to issue arrest warrants against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant for the commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

There is also Mishra’s puzzling treatment of the history of violence against Jews. He devotes dozens of pages to the machinery of the Final Solution, quoting from the work of historians like Raul Hilberg and Christopher Browning, theorists such as Hannah Arendt and Tzvetan Todorov, and witnesses like Primo Levi and Jean Améry. Mishra also writes movingly about how, growing up in India in the 1970s, he came to feel an “affinity for the uniqueness of the Jewish fate.” He describes how he became aware of the ways in which “the prejudices of white supremacists across the West connected Jewish to Asian and African fates,” and shares the anger and shame he felt when he thought “about the many Indians who read Mein Kampf as a lesson in genius nation-building.”

Moreover, Mishra confesses with touching candor that he had a photo of Moshe Dayan pinned to his bedroom wall and was gripped by Leon Uris’ novel Exodus. (He was not alone — I signed up for my first summer on a kibbutz while humming the movie’s theme song. In a story that may not have happened, but rings true, David Ben-Gurion once quipped that while the novel was trash, as a piece of propaganda “it’s the greatest thing ever written about Israel.”)

Yet, oddly, when it comes to more recent acts of violence against Jews, Mishra has little to say. His book is silent about the spreading rash of antisemitism, the gathering force of neo-Nazi parties, and the lengthening string of antisemitic attacks across Europe. As for the immediate cause to Israel’s invasion of Gaza — the Hamas attack that wiped out the lives of more than a thousand men, children, and women (many of whom were first raped), and took hostage more than 250 other Israelis and foreigners from the border communities — Mishra has alarmingly little to say. All he allows is that it “rekindled a fear of another Holocaust” before pivoting to “Israel’s livestreamed mass-murder spree in the Middle East.” When he condemns the “orgy of bestial violence,” Mishra illustrates this orgy with scenes of maimed and massacred Palestinian civilians, but not one of the Israeli civilians who died in their homes on Oct. 7 or in Hamas tunnels since then.

This insistence on the centrality of what occurred on Oct. 7 is more than a case of whataboutism where opponents batter one another with competing claims to victimhood. Instead, it is an appeal to attend to these competing claims and do full justice to both. My use of the verb “attend” is deliberate. In his book, Mishra approvingly quotes French thinker Simone Weil on the imperative to be open to “change sides, like Justice, that fugitive from the camp of conquerors.” This is true and important.

But no less important is Weil’s notion of attention, by which she meant the capacity to open ourselves up to the suffering of all people, and not just one subset or another. Paying attention to others means setting aside our fantasies and fears and setting about the task of seeing others. “Every time that a human being succeeds in making an effort of attention with the sole intention of increasing his grasp of truth,” Weil wrote, “he acquires a greater aptitude for grasping it.” This effort strikes me as the precondition for the flourishing of true justice in Israel and Palestine.