In WWII’s only all-female concentration camp, community was the key to survival

Lynne Olson’s book ‘The Sisterhood of Ravensbrück’ reveals the unsung stories of female French resistance fighters

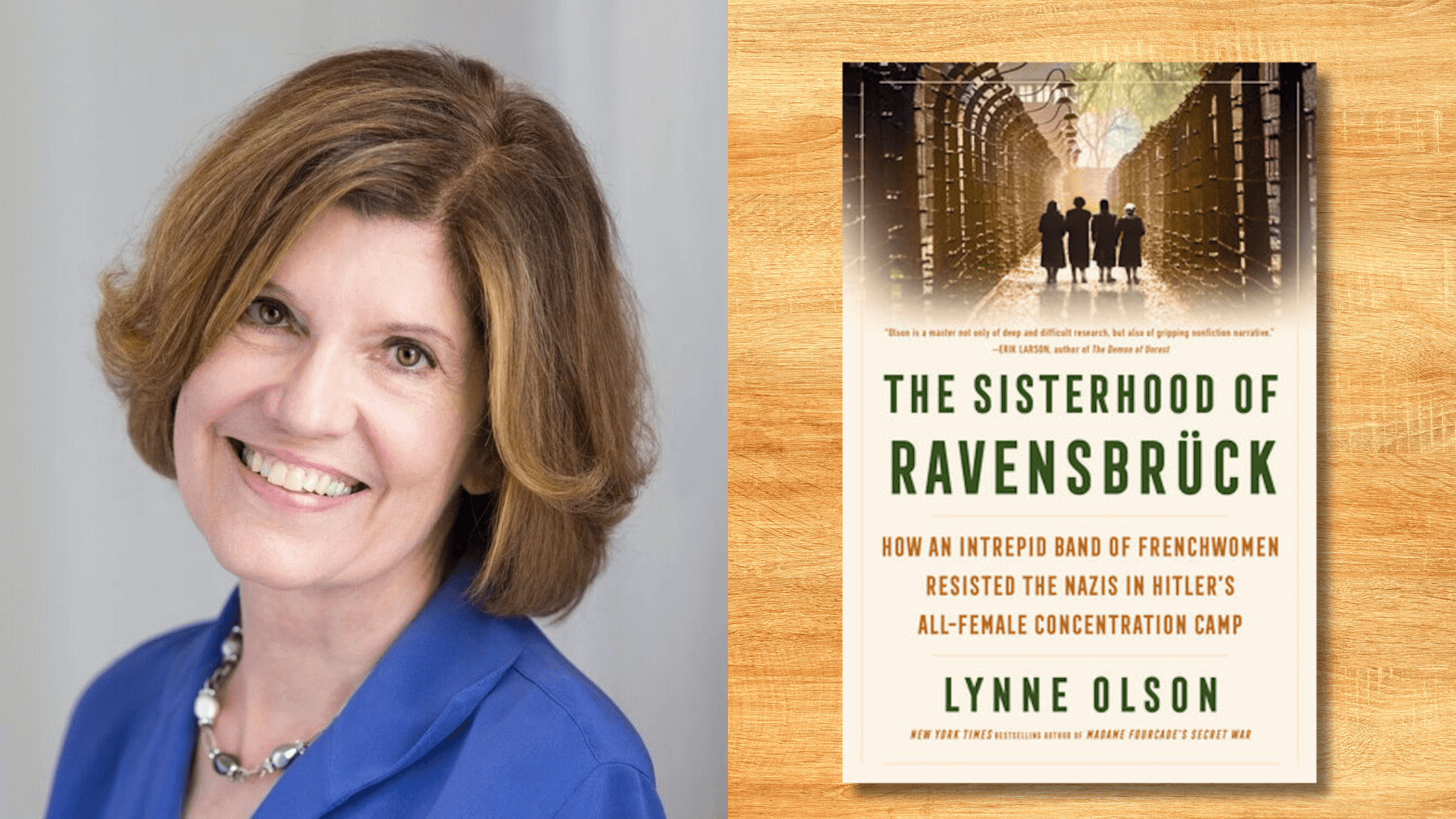

Lynne Olson’s new book, ‘The Sistehood of Ravensbrück,’ describes the lives and legacies of the survivors of the all-female concentration camp. Graphic by Canva

World War II isn’t a new subject for historian Lynne Olson. But her latest book, The Sisterhood of Ravensbrück, covers the unique story of the war’s only all-female concentration camp.

Olson, who previously worked for the Associated Press and the Baltimore Sun, wrote her most recent two books — Madame Fourcade’s Secret War and Empress of the Nile — about French women who participated in the resistance against Nazi rule. While researching these books, Olson came across the story of resistance fighter and anthropologist Germaine Tillion, who was sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Olson quickly found herself pulled into the story of how the camp’s prisoners created a loving community amid abhorrent conditions.

Centered around the camp’s four main leaders, Tillion, Anise Postel-Vinay, Geneviève de Gaulle, and Jacqueline Péry d’Alincourt, The Sisterhood of Ravensbrück is a detailed account of the women’s activism before, during, and after their internment in the camp. Despite camp officials’ attempts to foster animosity between the different nationalities at Ravensbrück – which included French, Polish, German and Czech prisoners — the women ignored these differences to help each other survive the forced labor, medical torture, and generally brutal conditions that they were subjected to, whether through lying, providing hiding spots, or sneaking goods to one another.

Olson says that this widespread camaraderie wasn’t as common in co-ed or all-male concentration camps and attributes that fact in part to the role society ascribes to women.

“We’re brought up with the idea that we take care of people, that we take care of our families, we take care of friends,” Olson said. “There was just much more of a sense of that inculcated in these women.”

The women’s proclivity for caretaking is particularly evident in a scene where the women discuss the food they can’t wait to serve their husbands once they are free.

Although the four main women had passed away before Olson began the book, she was able to to piece together their stories using the women’s memoirs and Sisters in Resistance, Maia Weschler’s documentary about Ravensbrück.

“I really got a chance to, in their own words, to hear what they had to say about what had happened,” Olson said.

Despite their essential role in the resistance movement, these women have often been overlooked. In the book, Olson notes that out of the 1,038 admitted in 1940 to Charles de Gaulle’s Compagnons de la Libération, an order honoring resistance fighters, only six were women. Although more attention has been paid to female resistance fighters in recent years, it’s not nearly enough considering the work they did, Olson says.

Olson describes Ravensbrück as “a forgotten camp,” saying that it has not received as much attention as other concentration camps.

“The concentration camps we’re familiar with now like Dachau and Buchenwald were liberated by American troops So there were a lot of American journalists covering the story,” Olson said. “Ravensbrück was liberated by the Soviets.”

Ravensbrück was also liberated later than many of the other camps, only six days before the war ended in Europe.

“People were not interested in focusing on the horrors at that point,” Olson said. “They were really interested in getting this war over and getting back to normalcy.”

For those who had survived the camps, forgetting the horrors wasn’t an option. After the war, the women of Ravensbrück stayed active in the fight for justice, helping create the National Association of Former [Female] Deportees and Internees of the Resistance, which provided female concentration camp victims with medical care, shelter and employment.

“They were traumatized, obviously, by what happened,” Olson said. “But the fact that they could get over it enough to not only to help themselves, but to have children, to have a happy home life, and to help others — that was what was so impressive to me, that they didn’t turn inward.”

Germaine Tillion, whose background in anthropology had moved her to keep detailed notes of the horror she witnessed at Ravensbrück, was instrumental in the prosecution of a number of the camp’s officials and the execution of two: Commandant Fritz Suhren and Hans Pflaum, the camp’s SS supervisor.

In the story of Ravensbrück, Olson sees a broader message about the nature of resistance.

“Ordinary citizens, no matter how horrible the situation they find themselves in,” she said. “They can actually make a difference if they come together.”