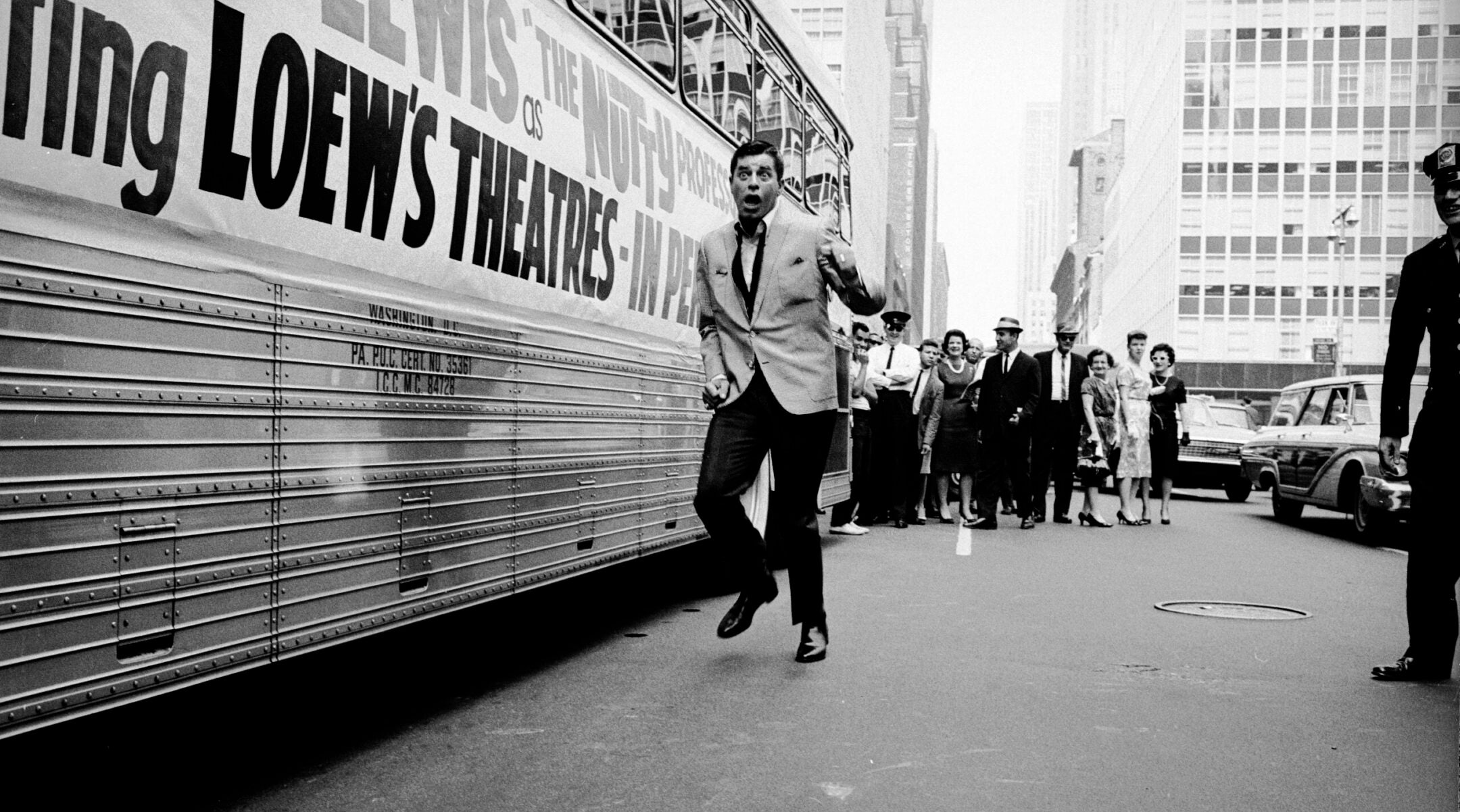

Legendary ‘King of Comedy’ Jerry Lewis placed a weekly Jewish deli order, his son recalls

Christopher Lewis’ book about his father explores the star’s Yiddish-speaking upbringing and his role in raising billions of dollars to fight muscular dystrophy

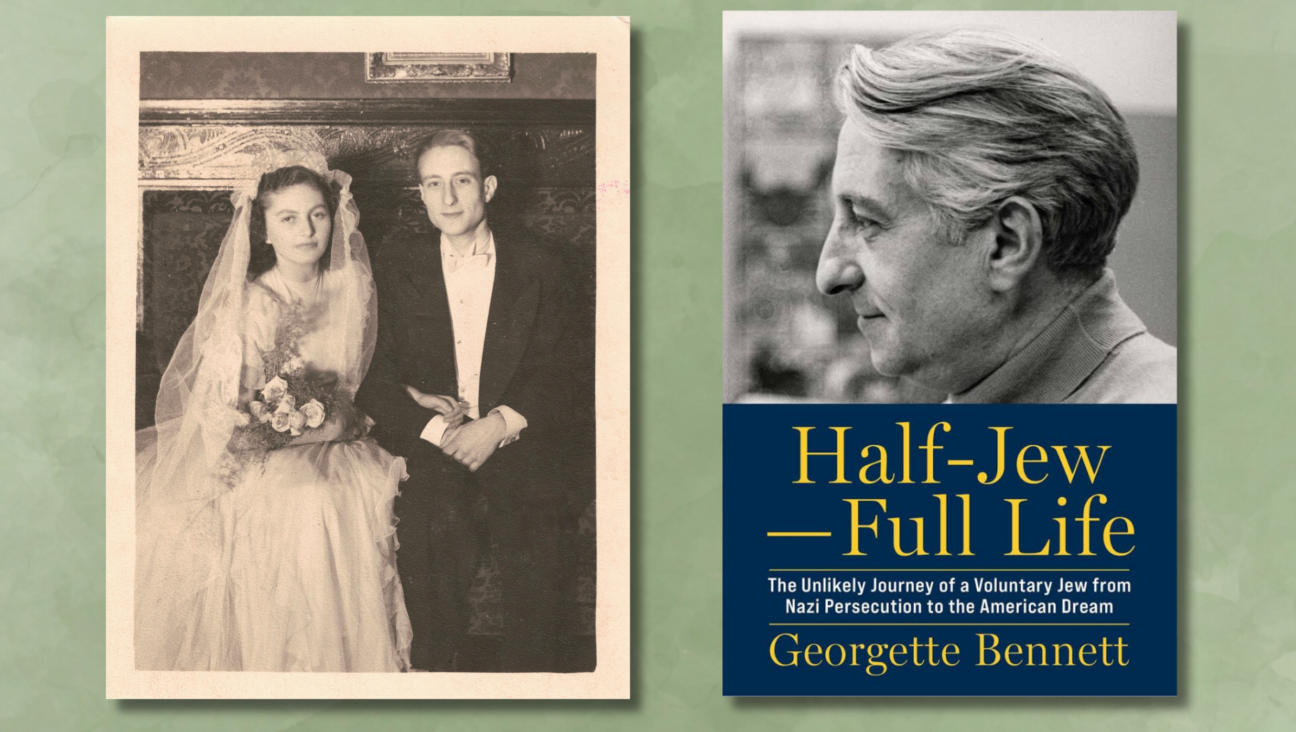

American comedian and actor Jerry Lewis pretends to run from adoring fans during the promotional tour for the film “The Nutty Professor,” directed by and starring Lewis, in 1963. (Arthur Schatz/Getty Images)

DALLAS — Christopher J. Lewis stood at his booth in the midst of a sprawling exhibit hall earlier this year as 2,000 physicians, researchers, pharmaceutical representatives, journalists and rare disease patients mingled in Dallas to mark the 75th anniversary of the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

Yet Lewis wasn’t here to hype the latest gene therapy or give lectures. Rather, he just wanted to tell his story — and that of his famous father, a Jewish funnyman who became closely associated with fundraising to combat the disease.

“I worked on the MDA Telethon for 39 years with my dad, and the MDA is a big part of my life,” he said. “I’m here because I want to learn about what they’re doing, how they’re doing it, and how I might be able to help.”

Lewis’s famous dad was Jerry Lewis, Hollywood’s undisputed “King of Comedy” — a Jewish entertainer who was born in 1926 as Joseph Levitch at Beth Israel Hospital in Newark, New Jersey. He died in 2017 at the age of 91 at his home in Las Vegas.

From 1966 until its finale in 2010, the Jerry Lewis MDA Labor Day Telethon — an annual event akin to the Super Bowl or the Academy Awards — raised some $2.5 billion for research into muscular dystrophy. During the course of the overnight telecast, an increasingly drained Lewis would bring on celebrity guests while an on-air tote board tallied contributions. He’d close the show with an emotional rendition of “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” from the musical “Carousel.”

Lewis, 71, said his father’s legacy “actually inspired me to start a foundation that delivers free wheelchairs around the world to people who need them and can’t afford them.” He spoke to JTA in between autographing copies of his new 314-page memoir, “Jerry Lewis on Being a Person.”

Christopher J. Lewis autographs copies of his book, “Jerry Lewis on Being a Person,” at the Muscular Dystrophy Association’s 2025 Clinical & Scientific Conference in Dallas. (Larry Luxner)

The book includes several details about Jerry Lewis’ Jewish upbringing and identity, which he neither denied nor emphasized once he was famous. For example, Chris notes, Jerry’s first language was Yiddish, a consequence of having been raised almost exclusively by his grandmother, Sara Rothberg.

“See, my dad was born to vaudevillians. His father was a singer, and his mother was a piano player. They lived the bohemian life traveling through the Borscht circuit of upstate New York,” Lewis explained. “He felt rejected. When an interviewer once asked my dad to describe his childhood, he said, ‘Tears of loneliness.’”

He added: “My father created the clown character to make people laugh, so he could feel loved and accepted. That was the core of his being, but until the day he died, he was the most insecure person on the planet.”

In 1939, Jerry Lewis celebrated his bar mitzvah, but his parents — Danny and Rae Levitch — were the only guests, and they couldn’t stay for long. As a teenager, the budding performer had several run-ins with neighborhood bullies, but always fought back, Lewis said of his father.

“These stories have been told so many times, and have so many different versions,” he said. “But he was definitely a street fighter. If anyone told him anything antisemitic, he’d go after them. He could not stand that sort of thing, and consequently he got into a lot of trouble.’

Lewis told JTA that his father “honored his Jewish faith very much, but he didn’t have time for organized religion. He’d say, ‘It’s in my heart.’”

Jerry Lewis did his first stand-up routine in 1942, at the age of 16, in the heavily Jewish Borscht Belt of the Catskills. Three years later, he and Dean Martin began their wildly popular singing and acting partnership, flooring night club audiences and teaming up as stars of their own radio program, “The Martin and Lewis Show.” The smooth Martin and the clownish Lewis would continue performing together until 1956, during which time they starred in 16 buddy movies from “Sailor Beware” to “Scared Stiff.”

It was around this time that the MDA was established by Paul Cohen, a Jewish businessman from New York who had facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy.

“One night, I asked my mom whether there was a secret reason why my dad did what he did for the people with muscular dystrophy. He always said when there was a cure, he’d tell everyone why he does it,” Lewis wrote in his memoir. “She remembered that he had met a family in 1949 who lost two boys with muscular dystrophy and had a third son ‘waiting to die.’ My mom said: ‘He came home in tears telling me we had to help these children.’”

The comedian did fundraising variety shows, alone and with Martin, sporadically until 1966, when the Labor Day Telethon became a regular fixture. The 21-hour show was broadcast on 213 TV stations — first from New York, and then after 1973 from Las Vegas — and viewed by tens of millions of families coast to coast.

A versatile actor, comedian, singer and filmmaker, Lewis’s most famous movies were “The Bellboy” (1960) and “The Nutty Professor” (1963), which critics have praised for the ingenuity and heart beneath the slapstick. Director Martin Scorsese gave Lewis a late-career boost in “The King of Comedy” (1982), where he plays a late-night talk show host stalked by Robert DeNiro. All told, Lewis appeared in 117 film and TV productions and was honored with two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

In a humorous 1953 birthday tribute preserved on YouTube, Martin fondly calls Lewis “my skinny Hebrew.” By then, the Levitch family had formally changed its name to Lewis — in order to sound less Jewish — and the entertainer’s new wife, a pianist named Esther Calonico, eventually became known as Patty Lewis.

Chris Lewis, who was born a year later in Los Angeles, said he wasn’t raised in an observant home.

“But once a week, he had just about everything on the menu from Lenny’s Delicatessen delivered to our house,” Lewis recalled. “My dad would say, ‘We’re having Jewish food tonight’ and my mom knew exactly what that meant. It was already on the table.”

Actor Jerry Lewis and wife Sandee Lewis sighted on June 6, 1986, at the Carnegie Deli in New York City. (Ron Galella, Ltd./Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images)

Asked if his father had ever attended Hebrew school, Lewis replied: “Later in life, he claimed to have done everything, but I don’t know what the real truth is. I do know that he had a very deep respect for Judaism because his grandfather was a rabbi in Pinsk. Our entire family from Pinsk, the Rudlovich family, disappeared after World War II. That was a pain he always carried with him.”

That pain may explain why Lewis, in the early 1970s, decided to film a Holocaust-themed tragicomedy called “The Day the Clown Cried.” Yet the movie was never completed or released, and Lewis — stung by rumors that it was his worst production ever — did his best to make sure it would never see the light of day.

In 1967, Jerry Lewis bought a plane ticket to Israel, but then the Six-Day War broke out and he was forced to cancel. He finally made the trip in 1981.

“When he came home, he had Tel Aviv stickers all over his luggage — and he traveled with 50 pieces of luggage,” his son recalled. “He loved Israel and said Tel Aviv was one of the nicest places he had ever been, but didn’t have time to go to Jerusalem.”

Chris Lewis, by contrast, has been to Israel seven times since 2010 on behalf of the Nevada-based American Wheelchair Mission he established in 2009. The charity has delivered some 800,000 new wheelchairs to disabled children and adults in 150 countries — including Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and Sri Lanka — at zero cost to the recipients.

In Israel, Lewis’s charity works with Chabad’s Terror Victims Project as well as the Jerusalem-based Yad Sarah, Israel’s leading national volunteer group. Several containers of wheelchairs were sent to Israel by the Iranian-American Jewish Federation following a recent fundraiser by Lewis at a Beverly Hills synagogue.

Jerry Lewis inspects a Magen David Adom ambulance during a March 1959 visit to the Hebrew Academy of Miami Beach, Florida. (YouTube)

“My mom was Italian Catholic, so we were all baptized as Catholics but raised with Judaism as part of our lives,” he explained. “And as I’ve become older, I’ve gotten much closer to the Jewish faith.”

According to his son, Jerry Lewis — regarded as the most effective fundraiser in TV history — often visited children hospitalized with muscular dystrophy but kept those visits low-profile.

“Well, he never talked about it, so I would hear about it from other people. He wasn’t going to come home and tell my mom, ‘Oh, I went to see this dying kid.’ He didn’t want anybody to know because it was personal between him and the family, and he did not blow his own horn.”

This is partly why Lewis, the son, decided in 2016 to write “the true story” of his father and the MDA — a task he finally finished in 2021 “after being stuck in the pandemic.” In fact, the book’s last 70 pages documents the comedian’s lifelong dedication to muscular dystrophy research.

“My dad had something that I inherited from him: a love of humanity,” he said. “It’s hard to describe, but I know from our Jewish background that he had an empathy for people in pain, because I inherited that from him too. That’s what he felt when he met that family who had lost their sons to muscular dystrophy. His love of humanity is what kept him happy.”

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.