Amid the terror of war in Ukraine, a stirring debut novel demonstrates the power of love and art

Sam Wachman’s ‘The Sunflower Boys’ is a novel of unmistakable authenticity and empathy

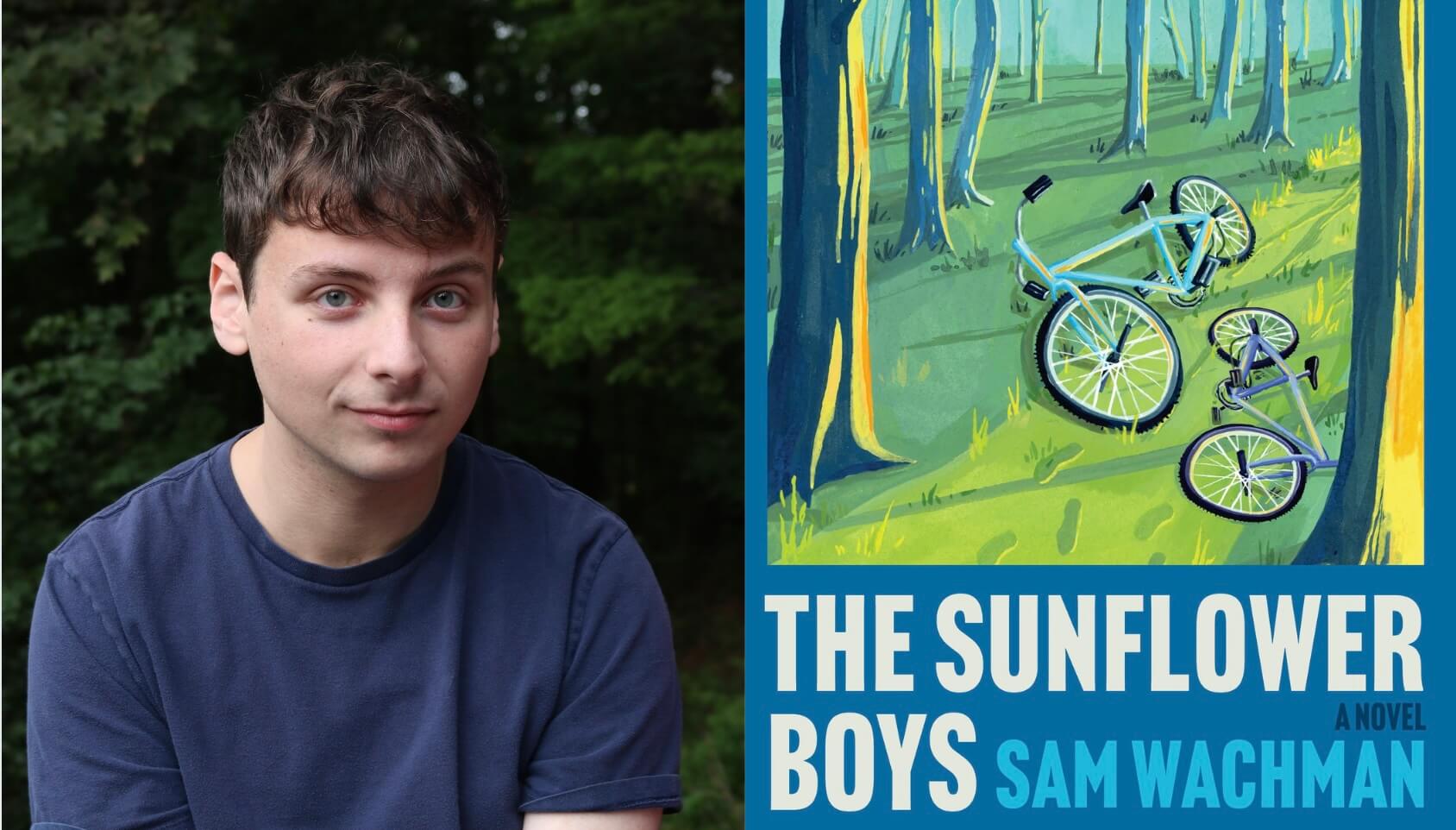

‘The Sunflower Boys’ is Sam Wachman’s debut novel. Photo by Paul Shelman/HarperCollins

The Sunflower Boys: A Novel

By Sam Wachman

Harper, 352 pp., $30

Imagine adolescence, falling in love, losing family and journeying across the precarious landscape of war. That is precisely what Sam Wachman has done, in convincing and dramatic fashion, in his debut novel, The Sunflower Boys.

The backdrop is Russia’s brutal 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Wachman, who has Ukrainian ancestry and speaks the language, has come to know the country well. He has taught English in a Ukrainian primary school and worked with refugee families in both Europe and the United States – experiences that seem to have left a powerful emotional mark. Wachman’s Ukrainian characters, infused with yearning but also tough and courageous, radiate an unmistakable authenticity. And his empathy for them quickly becomes our own.

The narrative begins in the riverside town of Chernihiv, north of Kyiv, in what feels like peacetime. (As Wachman reminds us, Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, and skirmishes in the Donbas, in eastern Ukraine, continued afterwards.) At first, Wachman’s 12-year-old protagonist and narrator, Artem, faces typical adolescent challenges. In lieu of paying attention in school, he prefers to draw and chat with his best friend, Viktor. And living with his mother and younger brother, Yuri, he misses his father, who is working in the United States to boost the family’s finances.

Tato (Ukrainian for “father”) stays in touch with video calls, postcards and gifts, including a sketchbook. But none of this can make up for his absence. “Our family long ago ossified around his empty space,” Artem thinks. During a rare visit home, Tato takes his sons hiking, prefiguring a more dangerous adventure to come.

Meanwhile, Artem has another problem — his growing attraction to Viktor, which manifests as “a tug in my belly that returns every time he is near.” Artem fears that his love won’t be accepted – by his family, friends or, most crucially, Viktor himself.

But such anxieties, huge as they initially appear, are subsumed by the terror of war. The only imperative becomes survival. When explosions rock Chernihiv, the family shelters with neighbors in a basement reeking of mildew and sweat. They decide to flee to the village, Vasyukivka, where Artem’s maternal grandfather, Did Pasha, lives. In fact, he is its only resident, along with “the cows that wander into the road and the willow trees and sunflower fields endlessly rustling in the wind.”

For the boys, this was once an idyllic spot, where they learned to fish and harvest herbs, vegetables and sunflowers. Pasha also told them of the famine Ukraine endured under Soviet rule and the horrors of World War II. “Our land is full of skeletons. We are a country with a phantom limb,” he said.

Even here, it turns out, the family is not safe. While Yuri and Artem hide, marauding Russians murder their mother and grandfather. Left alone, they are consumed by guilt. But not quite ready to give up on life. Artem’s coming-of-age tale becomes a quest story as the boys try to find their way home.

On the way back to Chernihiv, they encounter a surreal and desolate landscape of rubble and corpses, stranded tanks and bombed-out apartment buildings. They learn eventually that their hometown is inaccessible, and sympathetic grown-ups direct them instead to Kyiv. At this point, their only goal is to reunite with their father, who is on his way to Poland.

As Artem leads Yuri west across Ukraine, from Kyiv to Lviv, he dodges dangers and discovers unexpected reserves of resiliency and strength. Wachman’s portrait of turbulent, war-devastated Ukraine and its refugees is vivid. In mostly unadorned prose and short chapters, he immerses us in the boys’ plight.

“Death comes without any poetic or beautiful reason,” Artem learns. His father will tell him: “You saved each other, which is everyone you could have saved.” But it is an absolution for which Artem is unready.

While The Sunflower Boys demonstrates Wachman’s fondness and admiration for the Ukrainian people, it is not entirely a panegyric to the hobbled country itself. Though technically Artem’s father is exempt, as a single parent, from military service, Ukrainian bureaucracy is a forbidding obstacle. Getting back to Ukraine is difficult; getting out again is even harder. Tato hires a smuggler to effect a final, perilous mountain crossing, and the ordeal is more harrowing than expected.

The novel works on multiple levels. It offers a historically specific look at Ukraine, a celebration of same-sex love, and a meditation on the pull of home. Surefooted in both its craft and its theme, the novel also lauds and exemplifies the power of art — Tato’s stories, Artem’s drawings and literary fiction itself — to help heal the trauma of war. The larger political forces may be inexorable, but, Wachman suggests, an individual can still save himself, and maybe a handful of those he loves.