To play in the orchestra in Auschwitz was a gruesome affair, but it was better than the alternative

Anne Sebba traces the grim history of ‘The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz’

Holocaust survivor Anita Lasuer holds up a portrait of herself playing the cello. She survived Aucshwitz in part, because she played in the orchestra. Photo by Getty Images

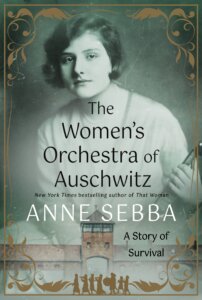

The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz: A Story of Survival

By Anne Sebba

St. Martin’s Press, 400 pages, $32

Being a musician in the women’s orchestra of Auschwitz-Birkenau was a gruesome endeavor. It meant playing brisk marches, under SS command, as other concentration camp inmates headed out to backbreaking labor — and then returned at night, exhausted or worse. It meant performing regular Sunday concerts for prisoners and SS guards. And, on occasion, it meant supplying a deceptive and calming soundscape for those being selected for the gas.

Still, being a musician was less gruesome than the alternative. Assigned their own barracks, orchestra members enjoyed better hygiene, skipped outdoor roll calls in the freezing Polish winter, and sometimes received supplements to the usual starvation rations. When they became sick, they had a chance of being nursed back to a semblance of health.

Anne Sebba notes in The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz that she has a personal link to the story: Her father was part of the British forces that liberated Bergen-Belsen, where some of the Jewish orchestra members spent the war’s final weeks. That connection, she says, impelled her to learn more about the Auschwitz women’s orchestra: how its members survived, and at what cost, and what their music-making meant to them and others.

Her book assembles accounts from both the orchestra and other former prisoners, with an emphasis more on comprehensiveness than readability. One challenge is the sheer number of people that pass through its pages. They offer a mosaic of recollections that sometimes make the loosely chronological narrative hard to follow. Sebba seems to realize the problem: She includes a reference list of orchestra members — among them two Hélènes and one Helena, as well as two Evas, two Marias, a Lili and a Lilly.

The book’s focus, to the extent it has one, is on Alma Rosé — niece of the composer Gustav Mahler, daughter of a famous Austrian violinist, and a violin virtuoso herself. Rosé was the most talented and effective of the orchestra’s three principal conductors during its brief existence, from April 1943 to October 1944. (Before Rosé, the orchestra was helmed by the Polish music teacher Zofia Czajkowska, and after her by the pianist, singer and Red Army officer Soja Winogradowa.)

An assimilated Austrian Jew who converted to Catholicism, Rosé was a controversial figure. She was ingratiating to her Nazi supervisors, especially the brutal but music-loving Maria Mandl, and a tough disciplinarian to her musical charges. “She inspired loyalty but she also aroused jealousy,” writes Sebba, who is mostly a Rosé defender.

The French singer and pianist Fania Fénelon, in an account that Sebba calls “novelized and sensational,” was particularly scathing about Rosé’s idiosyncrasies. Her book, The Musicians of Auschwitz, became the basis for the 1980 television film Playing for Time, starring Vanessa Redgrave and Jane Alexander.

Under perilous circumstances, and balancing conflicting imperatives, Rosé managed to mold a small core of musically gifted professionals and a variety of desperate amateurs into a creditable ensemble. She wanted the best players; to please the Nazis, she needed to recruit Christians as well as Jews; and yet she “seems to have been intent on saving as many young Jewish women as possible,” Sebba writes.

During marathon practice sessions, as the musicians struggled with hunger and fatigue, Rosé reminded them: “The orchestra means life.” Ironically, Rosé herself died, at 36, of what was probably accidental food poisoning, despite efforts by Nazi doctors — including the notorious Josef Mengele — to save her.

Sebba sees the musicians, forced into complicity with their oppressors, as denizens of Primo Levi’s morally ambiguous “grey zone.” And she understands that the subject of music in Nazi concentration camps — where there were many musical ensembles, but apparently just one all-female orchestra — is a vexed one.

Music could both heal and hurt; it could provide a fragile refuge from horror, or deepen trauma. For those able to compose their own music, play privately for themselves or other prisoners, or collect and catalogue the music of others, the exercise was often a salve. Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, a cellist at Auschwitz, later described one private concert as “a link with the outside world, with beauty, with culture, a complete escape into an imaginary and unattainable world.”

But the orchestra’s official duties aroused darker, more complex emotions. And the prisoners compelled to hear their music were often vituperative, with one survivor describing being forced to listen as “another way of killing us.”

“I realize that merely to speak of cultural life in the camps is a perversion, since this was a world never free of fear and full of crises, coercion, disease and death, all of which automatically destroyed or damaged anything of beauty,” Sebba writes. “Yet at the same time playing Mendelssohn, Chopin or Beethoven, forbidden music on the grounds that the composer was Jewish, Polish or too great for ‘inferior’ Jewish musicians, in secret, provided occasional moments in the darkest history of the 20th century when a handful of women showed their defiance of the Nazi system in which they were trapped.”

Sebba also emphasizes the importance of the orchestra’s friendship networks, affiliations mostly arising from a common nationality or language. By contrast, Jews and non-Jewish Poles were often at odds. In the end, orchestra membership saved at least 40 lives, Sebba says.

Along with collating other accounts, Sebba interviewed the orchestra’s last two living members, both in their late 90s: Lasker-Wallfisch in London and Hilde Grünbaum Zimche in Israel. After the war, Zimche told her, she never played music again. Through Sebba, the two friends, who had recently lost touch, were able to reconnect, before Zimche died in February 2024.