Kafka and Chicago taught him to love literature, Rodney Dangerfield taught him how to live it

With ‘Kaplan’s Plot,’ essayist and journalist Jason Diamond announces his arrival as a full-fledged novelist

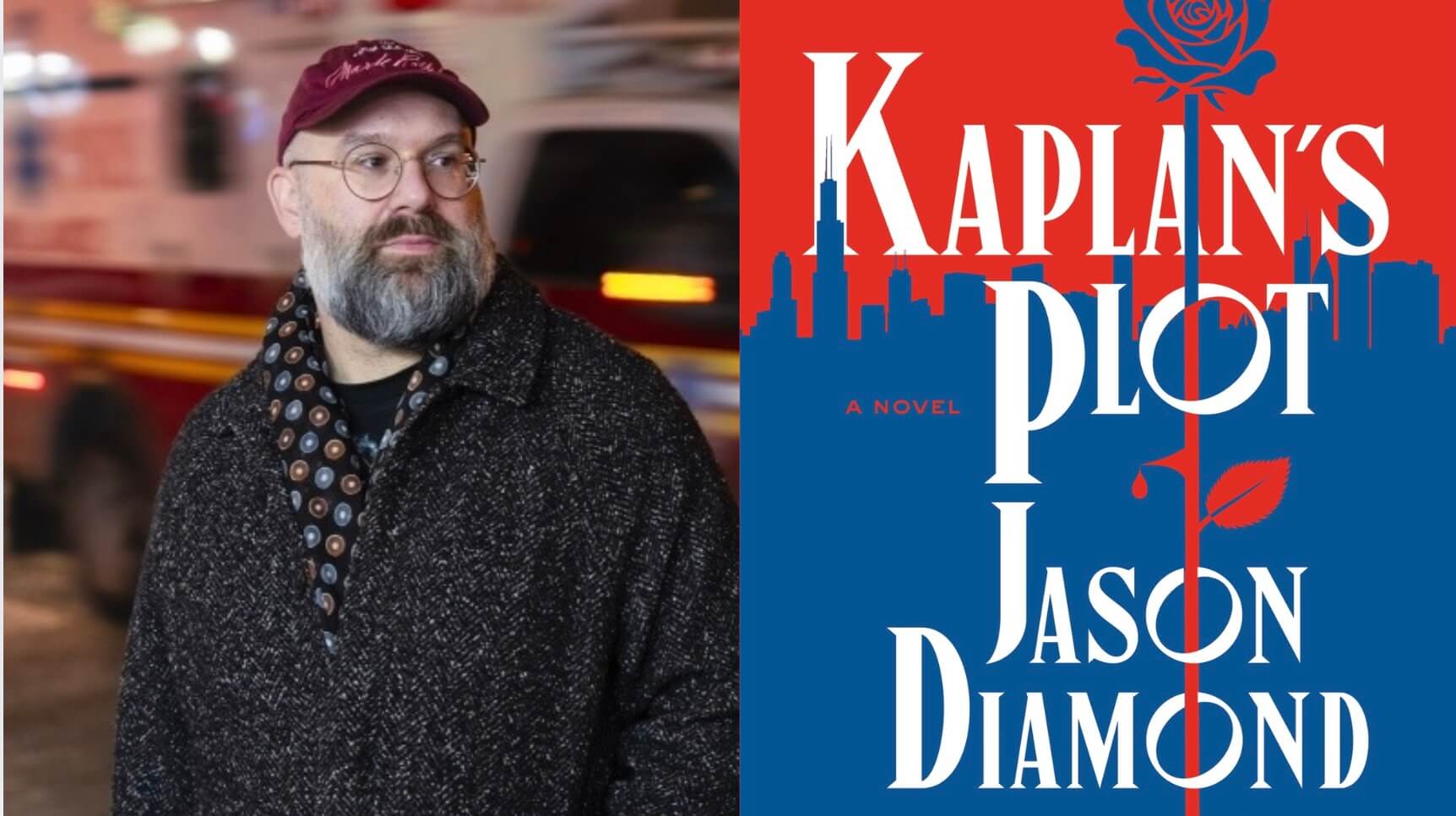

‘Kaplan’s Plot’ is Jason Diamond’s debut novel. Photo by Jeremy Cohen/Flatiron Books

New Yorkers have been eating at S&P Lunch in the Flatiron, the old Eisenberg Sandwich Shop reborn at 174 Fifth Avenue, since 1929. The back room hums. Everyone hears everyone. The tables sit close enough that pretending not to eavesdrop would make you the odd one out. The place reads Jewish-ish, secular, not kosher; a BLT on the board if you want to test the premise. It is the right place to meet journalist, memoirist, essayist, and now first-time novelist Jason Diamond.

When the server comes, I decree that here, by tradition, you order a plain tuna salad sandwich, not a tuna melt. The melts are fine here and elsewhere; truth is, most melts are. But here the lifers’ law is tuna salad. Before Jason can speak, Hannah at the next table leans in with the calm authority of another lifelong regular. “Straight tuna, no melt,” she says, enforcing the same rule as if she, too, had written it. She introduces herself as Jeff Stein’s mother, offering it like a credential. Her son is The Washington Post’s chief economics correspondent, now on leave writing a biography of Bernie Sanders.

A man, mid-pastrami, apologizes for the interruption. He introduces himself as Samuel Breidbart, a civil rights lawyer at the Brennan Center, and he tells Diamond he’s a fan. Diamond lights up and swears he didn’t plant him. The lawyer returns to his plate and his family. Hannah returns to her coffee. The din stays steady. Diamond takes the frame.

Born in Skokie and long based in Brooklyn, Diamond, 46, is known for pop-culture journalism and social-media posts that are actually funny. He has written a memoir, Searching for John Hughes in 2016, and, in 2020, The Sprawl, a wry nonfiction reconsideration of America’s suburbs. Now comes Kaplan’s Plot, a terrific debut novel that toggles between a grandson digging through family graves and the mobster rise of his Odessa-born grandfather, Yitz, on Maxwell Street.

The book moves between present-day Chicago and the turn of the last century. In the present, Elijah, a young man in the tech startup world who believes in little beyond money, cares for his mother, Eve, a poet dying of cancer. He stumbles into family secrets that threaten his shiny life and force him to decide what kind of man he is. In the past, two brothers arrive from Odessa, learning that survival is a craft — one behind a butcher’s counter with shining knives, the other in a city that runs on favors and implied threats. Real people inspired the story, but Diamond wanted fiction’s latitude to bend fact toward a truer arc, and that inventiveness is what I liked most. The book, by turns comic and sharp, bends history toward story until it feels both familiar and strange.

“I wrote the book fast, in nine months,” he says. I must look surprised, as he gives a small, unbothered half-smile. “I had been writing it in my head for 15 years.” He sold the book two weeks before his daughter was born, as tidy a plot twist as life offers.

Diamond talks the way he writes: fast, curious, lightly ironic, tuned to the quick cut that reveals a scene. His mother’s side descends from Chicago Jews who arrived after the turn-of-the-century pogroms in Russia; his father’s side landed in Brighton Beach after World War II.

When I ask how he met his wife, he laughs. “JDub,” he says, not JDate. JDub Records, the mid-2000s Jewish nonprofit label that launched Matisyahu. “She had just graduated and was a publicist. I showed up in a suit for a job I did not get. I did get her email.” They waited a long time to have a child — their daughter is now 16 months old. “We wanted to feel like grown-ups first.” Talk of his own family fades quickly into the family at the heart of his novel.

The true subject of Kaplan’s Plot is not gangsters but the mental injuries families pass along.

“Everybody in the book is damaged differently,” Diamond says. Yitz, a boy in Odessa, wanted to cry and never learned how. He smothered tenderness, turned survival into law, and carried it forward. That harm ripples into Eve, the poet-daughter dying with her secrets, and into Elijah, the grandson who mistakes money for meaning and cannot find his footing. “Yitz and his brother only knew survival,” Diamond says. “Elijah inherits the itch and tries to translate it into modern life.”

Diamond treats Jewishness like weather, not an argument but the air you move through. He grew up attuned to low-grade antisemitism, never constant but present enough to register. “From early on, I knew there was an us and them in the room,” he says. “I want to like everybody. But it is there.” The immigrant script provides the props. Chicago provides the stage, South and West Sides, Jewish and Black neighborhoods within walking distance and yet worlds apart.

Chicago leads his list of literary touchstones: Sandra Cisneros (The House on Mango Street), the poetry of Gwendolyn Brooks, and Saul Bellow, equal parts genius and aggravation. Diamond started as a critic, worked at Flavorwire and elsewhere, edited Jewcy.com, then decided to write only what felt true. “Five, six years ago I stopped doing filler,” he says. “I seized the means of production,” which in practice meant writing what he believed, in his own voice.

Diamond grew up around secular Yiddish, crackling, all elbow and eyebrow, and he is careful about how it lands. Too much and it turns into a cartoon. Too little and you sand the life right off. He keeps accents light, cadences true, and lets humor come from behavior, not spelling. I mention Grace Paley, and he tilts forward. A Paley story showed him how to bring Rose, a Chicago Holocaust survivor, onto the page without sentimentality. The Coens are in his toolkit too, with the clean snap of moral jokes where the funny and the unbearable share a seam. If they are reading, he would not mind their names on the adaptation.

Storytelling has always been his engine. He was diagnosed with ADD when he was a kid, before the ADHD relabel, and his parents were told not to expect much. He shrugs. What others call a deficit, he calls an engine. “It is not that you cannot pay attention. It is that you pay deep attention to a few things.” That is how a first novel gets written in under a year after 15 years of ideas brewing, all while parenting and filing punchy pieces. A creative nonfiction take on the Ramones is already sold to Flatiron. A second novel is close behind.

After a bite of rugelach, he tells the story of how fiction first clicked. In high school he asked an English teacher how to fix a bad grade. She told him to read Kafka. He knew the word Kafkaesque. He found The Metamorphosis and wrote two pages arguing it was the funniest story he had ever read. Hilarious and horrifying at once, it felt written for him. “My teacher, Ms. Sheehan, not Jewish, said, ‘You think this is funny? He turns into a bug. It is an existential nightmare.’ And I said, ‘It is funny because he turns into a bug and his parents do not know what to do.’”

College did not take, though he tried more than once, and the MFA versus life debate can go on without him. The model he favors is Rodney Dangerfield, the loud man in the quiet room, the person who is not supposed to belong and refuses to leave. He wrote about food when he wanted to, not because someone filed him under “food guy.” He will not be a Jewish novelist in the traditional sense, and he will not shy from the subject either. He wants to write as both a Jew and an American and meet the general reader where the overlap is strongest. “I want somebody Chinese or Italian or Mexican to see their American story in this,” he says. “It is the same machinery. How families move through time.”

In his memoir he wrote about a father, now sober, whose drinking led to violence, and about long stretches of estrangement from his mother. “I want to banish the myth that everyone has a Mrs. Goldberg mother,” he says. Fine to print, he adds; he has already put it on the record. He felt seen in the scrappy tenderness of Dave Eggers’ A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. You can still hear his film obsession in his sentences, the blocking, the cuts, the moment a scene earns its close-up. “I learned a lot about fiction from directors,” he says. “How they think about story.”

I press him on family. Who will be the one to kvell, the older relative who brags to strangers in line at Publix? When my first novel, The Unexpected Salami, came out in 1998, my mother practically put up billboards in Florida. On the walk over, I spotted a lone copy at the Strand, which, in honor of my biggest champion, I remembered to hand him.

“My mother-in-law,” he says. “She is amazing.” His parents will likely read it, and his maternal grandmother too, even at 95. “She is tough. She is sharp.”

Did his grandmother read the Forward in Yiddish, as my socialist grandmother did? He pauses, then laughs. “Some people in my family read the Forward. My Nana was Der Tog, The Day” — the rival Yiddish daily, later folded into the Day–Morning Journal. “She has been allergic to anything socialist ever since the family legend about an ancestor in Russia or Poland who declared himself the secular Jewish messiah.” Is she a Republican? He waves it off. “I do not know. She liked Obama because he is from Chicago.”

On his maternal side the family line is simple. If cancer or cigarettes do not get you, you live to 100. I tell him I have a few superagers of my own. My father died just shy of 100, and my Aunt Paula made it to 102. He laughs. “It has to be the Ashkenazi spite. It is our cardio. We keep going. It is a big F.U.”

The last thing we talk about is want. Not prizes, not film options, though both would be nice. He wants a reader to close the book and feel that a knot has been untied. It is easy to picture him back at a desk later, setting this table down on the page, the Cel-Ray sweating, the rugelach flaking, Hannah’s ruling on melts, Breidbart’s apology, the sound of many New York voices in a classic joint. Outside, the street hums in the heat, the same rhythm as the back room, only louder. Inside, somebody dares to order the tuna melt.