Cheating partners, antisemitic neighbors, and lost loves populate these Jewish worlds

Jennifer Moses’ new collection of short stories explores troubled relationships through a Jewish lens

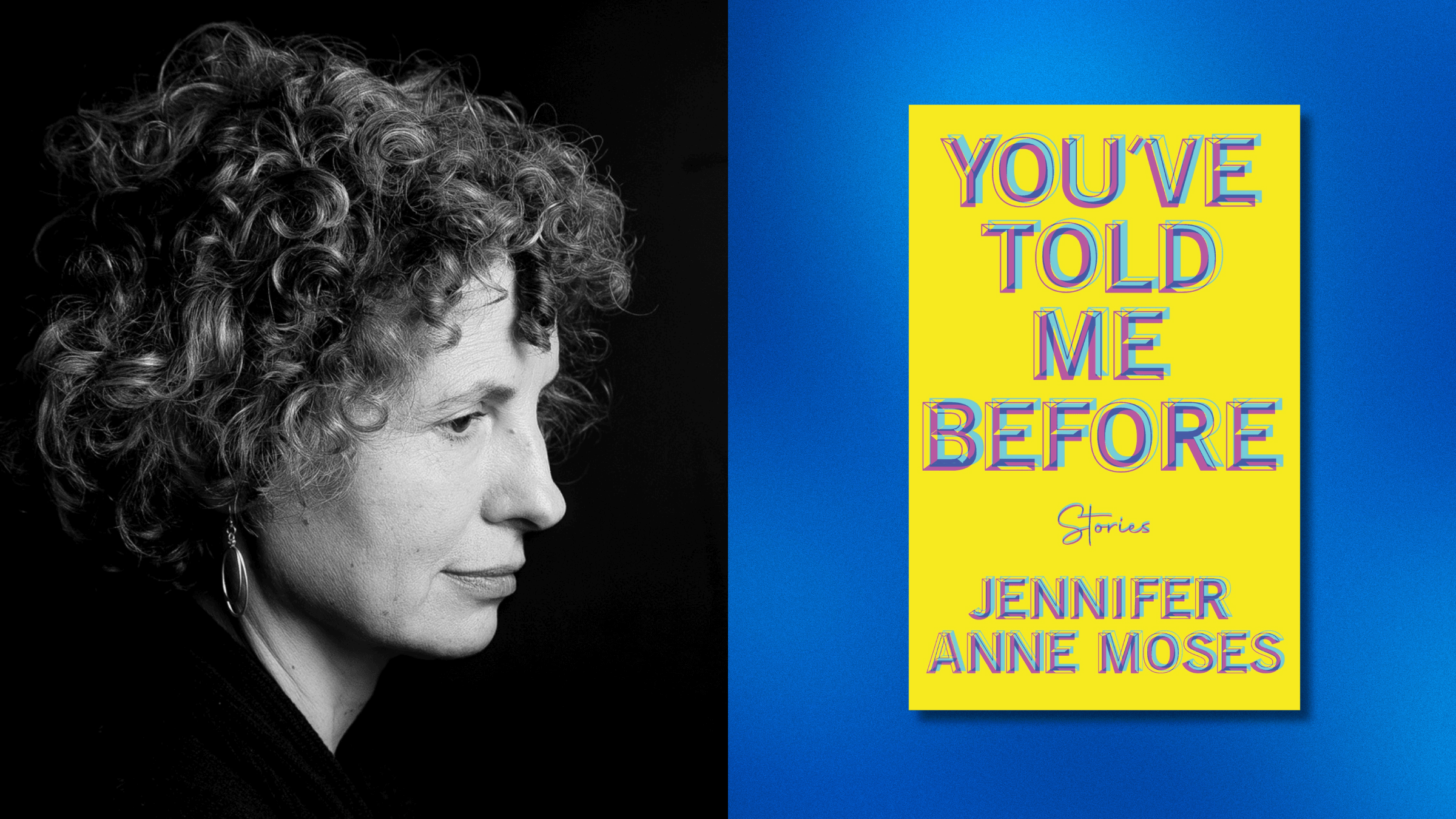

Photo by Nick Levitin/cover designed by Jordan Wannemacher/collage done in Canva

You’ve Told Me Before

By Jennifer Moses

The University of Wisconsin Press, 198 pages, $18.95

For most of her childhood, author Jennifer Moses didn’t feel a connection to Judaism.

Raised in the Waspy suburbs of Washington by an Orthodox father who treated Judaism as his personal practice, she had no formal Jewish education. Moses’ Reform mother primarily engaged with her Jewishness through social activities.

“I didn’t know an alef from a bet. I didn’t know the difference between Talmud and Torah,” said Moses. “Dad said we kept kosher because we didn’t have ham in the house.”

It wasn’t until she stumbled upon Yiddish literature that she really connected with her heritage — and began writing Jewish stories herself.

In her new short story collection, You’ve Told Me Before, her characters, connected to Judaism in a variety of ways, deal with strained and complex relationships, whether they be romantic, platonic, or residential. Dealing with unfaithful partners, broken engagements and bigoted neighbors, her characters try to resolve their conflicts — with varying degrees of success. The stories range from the humorous — a battle between the editor of a magazine on dying languages and an author of self-indulgent novels — to the more serious — a woman coming to terms with her husband’s sexual immorality. But they all carry a Jewish essence.

Personal elements from Moses’ life are scattered throughout. Like the heartbroken Emma in “The Young People’s Party,” Moses grew up in the suburbs of Washington with a lawyer as a father. Her parents had to deal with neighborhoods where Jews were not allowed to live like the couple in “The Goy.” Some of the characters, like her mother, are only Jews socially. The character Hannah, like Moses’ youngest son, is baal teshuva — a Jew who has become more observant.

Although Judaism plays a prominent role in the stories, Moses doesn’t view her intended audience as only being Jews.

“All fiction has to be specific to its roots, right? So you and I understand Jane Austen, even though we don’t necessarily get every reference,” Moses said. “You don’t need to be inside the culture if the writer is doing her job.”

At the heart of each story are emotions and conflicts that most people have experienced. Plenty of people can relate to being jealous, even if they’ve never felt it in the context of the Jewish literary world or expressed it in a pointed Tablet article, as the protagonist of “The Jewish Wars” does. Non-Jews can still experience the trials of an interfaith relationship, even if the challenge isn’t specifically in the form of a partner who’s had enough of sitting through long bar and bat mitzvahs.

“We are really odd creatures, human beings. We’re odd and we feel so deeply and we do such terrible things and we get hung up on such nonsense,” Moses said. Jews especially, she said, are “either liberated or saddened by — or both — by a particular and very old way of understanding our place in the universe.”