The Nazis sent them to Hawaii to spy for the Japanese

in ‘Family of Spies,’ Christine Kuehn confronts a past that is stranger and more sinister than fiction

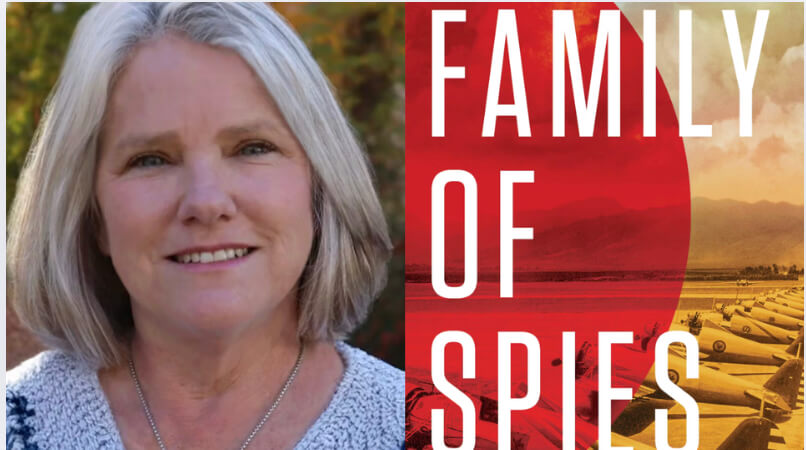

The history behind Christine Kuehn’s Family of Spies may recall the TV series The Americans. Photo by Emily Burkhard/MacMillan

Family of Spies: A World War II Story of Nazi Espionage, Betrayal, and the Secret History Behind Pearl Harbor

By Christine Kuehn

Celadon Books, 272 pages, $30

Surely this must be historical fiction.

Here’s the premise: In 1930s Germany, a teenage girl has an affair with chief Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels. When he somehow discovers she is half-Jewish, her immediate family (excepting one ardently Nazi brother) is banished to Hawaii, where mother, father and daughter are tasked with spying for the Japanese — and facilitating the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Decades later, an American writer inherits this unlikely story and the resulting generational trauma. She sets out to uncover more details, spurring an intermittent, emotional 30-year quest and, finally, this book, Family of Spies.

Which, it turns out, is not fiction, but rather an astonishing blend of history and memoir.

“Christine Kuehn was cocooned in the sanctity of a quiet suburban life when a mysterious letter in 1994 pierced that bubble,” the author’s biographical blurb states. The letter, from a screenwriter, seeks information about a grandfather involved with the Nazis. It sends the skeptical Kuehn and her husband to a bookstore, where, in the World War II section, sure enough, they find scattered references to a man named Otto Kuehn and his daughter, Ruth. Both are linked to anti-American espionage.

By this point, Otto and his wife, Friedel, are dead. So, too, is Leopold, the brother who stayed behind and fought for Germany during the war. But living witnesses remain: Christine’s father, Eberhard, and, even more tantalizingly, Ruth herself.

“You don’t need to know about the family, the past, or Pearl Harbor,” Ruth had told Christine years earlier. Christine’s father, too, had supplied only “vague, whitewashed snippets” about that past.

But after some prodding, Eberhard Kuehn shares memories of his Hawaiian boyhood, an idyll of swimming, surfing and fishing during which he was unaware of the family’s spying. When the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor happened, on Dec. 7, 1941, he was 15 and, though not yet a citizen, thoroughly American. He enlisted in the U.S. Army as soon as he could, fought at Okinawa, and remained estranged from his parents for the rest of his life.

As Christine investigates, Eberhard, always a teller of fantastical stories, is gradually ravaged by dementia. His recollections fade, leaving her to continue her fraught pilgrimage through family history alone.

As for Ruth — if this were indeed a novel, the climax would be a confrontation between aunt and niece, with attendant revelations. But Ruth is intent on concealment. On a visit to Germany after her mother’s death, she and another brother, Hans, burn a cache of family papers. She dies having kept her secrets.

Kuehn’s narrative weaves back and forth between the history itself and her quest to discover and decipher it. She reports deeply on the intricacies of espionage and counterespionage in Hawaii, relying largely on FBI files. Her structure and style are clear and effective. But it is really the improbability of the tale that hooks readers.

Its precipitating events take place in Berlin, where Ruth, like the rest of the family, is immersed in Nazi culture. Encountering Goebbels, a vicious antisemite who is also a charming womanizer, she succumbs, and for a while he does, too. But it turns out that her biological father is not Otto Kuehn, a failed businessman trying to rise in Nazi ranks, but a Jewish architect with whom Friedel was involved before the marriage. That, of course, is a problem.

Otto Kuehn’s own history includes missteps and near-misses. One family anecdote has him loaning the financially strapped Rudolph Heydrich, his competitor for a top SS post, train fare to get to the job interview. Heydrich beats Kuehn out for the position, later becoming Gestapo head and a key architect of the Holocaust.

Meanwhile, Otto works as a secret agent, first for the Weimar-era German navy and then for the Nazis. So, drafting him, in 1935, for Hawaiian espionage makes a certain sense. But in his granddaughter’s telling, he is “vain, grandiose, a risk-taker,” a less-than-superlative spy. He and Friedel are too ostentatious, parlaying cash windfalls from their Japanese handlers into real estate purchases and lavish parties. Ruth is seemingly more subtle in prying military information from U.S. naval officers charmed by her. “Dating was the perfect cover,” Kuehn writes.

At one point, Ruth becomes engaged to a German steel executive living in Tokyo, a man who happens to be the family’s Japanese handler. But when Friedel travels to Japan to collect money owed to the Kuehns, she finds Ruth’s fiancé living with another woman.

Here, the story (which evokes the great FX spy thriller The Americans) becomes stranger still. The FBI and U.S. military intelligence have by now grown suspicious of the Kuehns. An FBI operative, Robert L. Shivers, is assigned to Honolulu in 1939 to stake out the family, as well as other suspected spies. A cat-and-mouse game of surveillance and surreptitiousness erupts.

One of Otto’s principal contributions to the attack on Pearl Harbor was devising a code that involved using light signals to broadcast U.S. ship movements to the Japanese military. Cables from the Japanese consulate to Tokyo describing the signals were intercepted by American intelligence, but not decoded or translated until after the attack.

Kuehn describes the terror of Pearl Harbor, with its massive American casualties and damage to the U.S. Pacific fleet — and what happened to her family next: imprisonment, separation, wandering, exile, a biblical level of catastrophe. Otto, convicted of espionage by a military tribunal, barely escaped a firing squad. But imprisonment with hard labor broke him, and his subsequent life — first in Argentina; then in Germany, with Friedel — was unhappy. It cannot have helped that after leaving the United States he never saw his son Eberhard again.

While there is no climactic confrontation with Ruth, Christine does find some closure by traveling to Germany. There, long-lost cousins share documents and photos and help her collate the family history. Lisa, who had reached out to her, is the daughter of Otto’s brother. “We are very excited for you to tell the story,” she tells Christine, marking the end of an intergenerational conspiracy of silence.