He could have avoided persecution in Nazi Germany — he got bar mitzvahed instead

‘Half-Jew — Full Life’ tells the story of Gerd “Pips” Phillipsohn’s life before and after Hitler came to power.

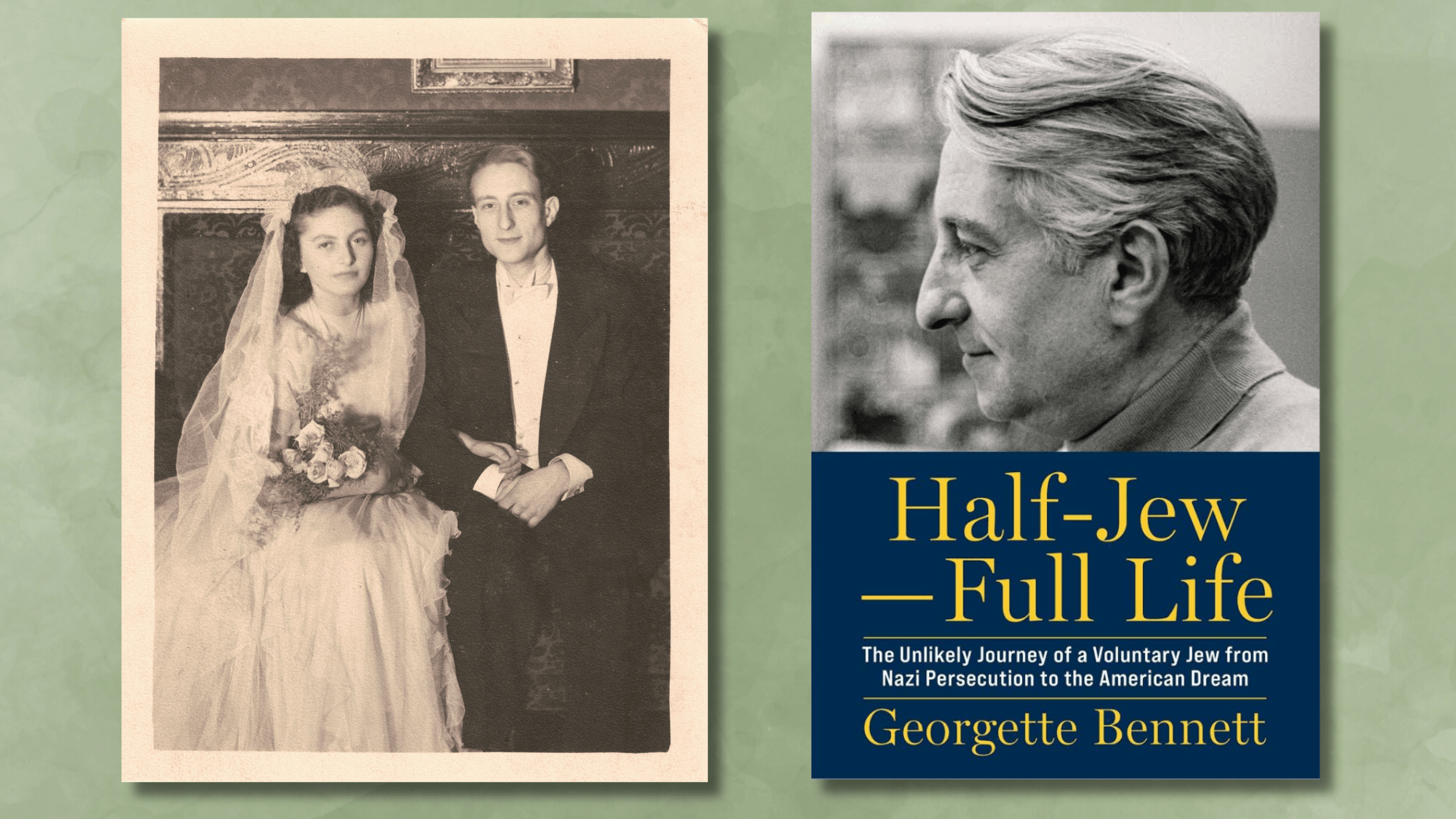

Gerd “Pips” Phillipsohn and his wife Olga on their wedding day, November 30, 1945. Courtesy of Jane Wesman Public Relations

When Nazi Germany enacted the Nuremberg Laws on Sept. 15, 1935, being a Jew suddenly meant losing citizenship and the basic rights that came with it. But that same week Gerd “Pips” Phillipsohn — born to a German-Jewish father and Aryan mother — chose to embrace his Jewish identity with a bar mitzvah.

The Nuremberg laws stipulated that a Mischling — a child with one Aryan parent and one Jewish parent — born before September 1935 was considered to be a citizen of the Reich. However, once Pips became a bar mitzvah, he forfeited that status and was considered a full Jew.

Pips, who miraculously survived the Holocaust and became an immigrant success story in America, is the subject of Half-Jew — Full Life by Georgette Bennett. Bennett, a sociologist and founder of the humanitarian organization the Multifaith Alliance, first met Pips, her mother’s cousin, in New York in 1952, when she was five years old and straight off the boat from France with her parents, both Holocaust survivors. When Bennett’s father died one year later, Pips became her father figure for the rest of her life.

Before he died in 2015, Pips gave her recordings of his sessions with a psychiatrist and the permission to write a book about his story, which she did in painstaking detail that makes the reader feel like they, too, have known Pips their whole life. Although Bennett knew much of Pips’ story already, the process of writing the book gave her a new perspective.

“It wasn’t until I read through the transcripts of all of his audio tapes that the story developed much more meaning to me because yes, it was in his own words, but in the kind of detail that even stunned his psychiatrist,” Bennett told me in an interview. “I understood him in a whole new way.”

Born in Berlin in 1922, Pips was raised by two fairly non-religious parents; his mom went to church at Christmastime and his father attended synagogue only for the High Holy Days. It was antisemitism that actually pushed Pips towards embracing his Jewish identity. Bennett writes that when Pips was six, his religion teacher’s assertion that Jews were Christ-killers prompted him to stop attending the class. After Jews were banned from German youth groups, he joined a Jewish youth organization instead. His whole life was suddenly Jewish and he thought that becoming a bar mitzvah would help him fit in socially — plus, he knew he knew his parents would buy him a new bike.

Pips later fell in love with a childhood friend, Ilse Rosenthal, and went into hiding with her after her family was given a notice of deportation. After a few months on the run, they were caught by the SS and separated. Pips eventually ended up at Grosse Hamburger Strasse, a prison and deportation site, and Ilse was sent to Auschwitz where she died.

Although Pips’ prison was known as the last stop for Jews bound for Auschwitz, he managed to survive through the end of the war.

“Not only did he suffer persecution at the hands of the Nazis, he lost everything,” Bennett said. “But they saved his life on several occasions.”

Prisoners were forced to work, and Pips once fixed windows for a woman he referred to in the tapes as Frau Heim, an employee in the Gestapo’s records department. When she learned he had been chosen to be deported to Auschwitz, she slipped his file behind a filing cabinet so the order couldn’t be processed.

But despite this and other occasional acts of kindness, prejudice never ceased. After Frau Heim saved his life, Pips witnessed her playing happily with her dog next to a truck full of Jews bound for Auschwitz. Bennett told me that Heim wasn’t “completely oblivious to what’s happening to these people” and had “zero empathy” for most Jews. But she knew Pips had an Aryan mother.

“When it came to him, she had a lot of empathy,” Bennett said. “She didn’t really see him as a Jew.”

While imprisoned, Pips met Olga, a Transylvanian deportee who escaped the death march from Auschwitz, and they married in 1945. Two years later, they immigrated to the United States, where Pips Americanized his name to Gerald Phillips. In just under two decades, Pips went from waiting tables in the Catskills to being a partner in Globe Photos, one of the largest picture agencies in the world at the time. The couple became wealthy enough to live at 860 UN Plaza, where fellow residents included Robert Kennedy, Truman Capote and Angela Lansbury.

Despite surviving impossible odds, Pips never considered himself a remarkable person.

“I think he may have been judging himself in relation to other people who achieved great things, who raised children,” Bennett said. “He didn’t see himself as having done any of those things.”

Regardless of whether or not Pips considered his life extraordinary, Bennett believes it holds important lessons.

“It’s a story about how a normal society can descend into the worst kind of autocracy and brutality,” Bennett said. “It’s a story about identity and the price that we pay for our identity.”

“It’s also about denial, you know, our ability to be in denial as we see the world collapsing around us,” Bennett added. “We see a lot of that going on today.”

Bennett noted that when Pips watched Brownshirts march down the street and heard that Jews were banned from working in the press, he wasn’t able to process the implications this had for him or his family.

“He was a very self-centered guy, which I think was part of his secret to survival,” Bennett said. “He never saw himself as a hero. And I don’t see him as a hero either. He saw himself as a survivor.”

Half-Jew — Full Life will be published by Skyhorse Publishing on January 27.