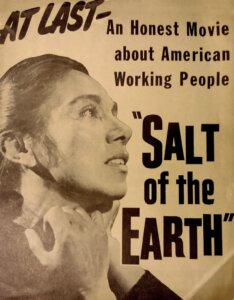

How blacklisted Hollywood artists joined forces to make a truly subversive film

Released in 1954, ‘Salt of the Earth’ was inspired by a 1951 strike against the Empire Zinc Company in New Mexico

Herbert Biberman, at left, with screenwriter Samuel Ornitz. Photo by Getty Images

Released in 1954, The Salt of the Earth, which was arguably the only major US indie film made by Jewish leftists, was a product of the enduring optimism of progressive thinking.

It was directed by Herbert Biberman, one of the so-called Hollywood Ten, a group of leftist filmmakers (six of them Jews) blacklisted and jailed for contempt of Congress after refusing to answer questions from the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1947.

Emerging after six months in stir at a federal institution at Texarkana, Texas, Biberman was undeterred; he and like-minded Jewish colleagues decided that if they were sanctioned for supposed subversion, the only thing to do was to create truly subversive films.

As the producer Paul Jarrico (born Israel Shapiro) later recalled to an interviewer, Salt of the Earth was their chance to really say something, because they had already been punished by the blacklist. “We wanted to commit a crime to fit the punishment,” Jarrico’s biographer Larry Ceplair quotes him as saying.

Other Jewish contributors to the film included the actor David Bauer (born Herman Bernard Waldman), composer Sol Kaplan, theater owner Simon Lazarus, and consulting director/assistant editor Leo Hurwitz.

Salt of the Earth was inspired by a 1951 strike against the Empire Zinc Company in New Mexico. In the film, Mexican-American women take over a picket line when their husbands are banned from participating. The film, Jarrico said, was “unequivocally prolabor, prominority and prowomen.”

Because of its feminist, anti-racist, and economic views, Salt of the Earth, which was investigated by the FBI and rejected by distributors and the movie projectionist’s union, has gained a reputation as being the only film ever blacklisted by Hollywood; otherwise; the blacklist focused on individuals, not specifically their creations.

As a result, at first it was only shown in a scant few theaters nationwide, like a venue in San Francisco’s Chinatown that otherwise screened only Chinese language offerings. In New York, it was projected in a theater whose owner warned moviegoers on the marquee that it was a “Left-wing Controversial Film.”

Reviews were mixed at first. Pauline Kael, despite the fact that she had been raised by Polish Jewish émigré parents on a chicken farm in Petaluma, California, panned it in Sight and Sound as a simple-minded “morality play” and “as clear a piece of Communist propaganda as we have had in many years.”

However, the Canadian Jewish drama critic Nathan Cohen lauded Salt of the Earth on CBC radio as an “exciting experience, a deeply human drama in the documentary manner perfected by the Italians in such masterpieces as Open City, The Bicycle Thief and Shoe Shine.”

With time, the film acquired an aura of prestige, shown repeatedly at social action events in the 1960s and ‘70s. Linguist Noam Chomsky, another admirer, explained that Biberman’s brainchild accurately illustrated how unions organize strikes.

Cinema historian Jonathan Rosenbaum’s viewpoint became representative, calling it “leftist propaganda of a very high order, powerful and intelligent even when the film registers in spots as naive or dated.”

The naïveté may be partly due to the film’s visual style, plainly influenced by the early Soviet propaganda films of Sergei Eisenstein, himself of Russian Jewish origin.

Biberman originally intended the lead female role for his wife, Oscar-winning actress Gale Sondergaard, who before the Hollywood blacklist had capsized her career, had memorably played Lucie Dreyfus, the wife of disgraced Captain Alfred Dreyfus (Joseph Schildkraut) in The Life of Emile Zola starring the Yiddish theater star Paul Muni.

However, all the participants concurred that having genuine Latino actors would be preferable to having Anglo actors in brownface. So Sondergaard stepped aside in favor of Rosaura Revueltas, an experienced Mexican actress from a distinguished artistic family. Revueltas never achieved worldwide fame because she was deported back to Mexico while the film was still being shot, as a deliberate move by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) to discourage the politically verboten film.

Movie historians Deborah Silverton Rosenfelt and James Lorence have detailed the myriad other attempts to stop the film from being made and of suppressing it after it was completed. The fact that it exists at all is due in large part to forthright optimism of American Jews who were undaunted even when their careers and livelihoods were destroyed and their family’s security threatened.

When Biberman was in prison, for example, and saw that Hollywood Ten jailbird, Jewish screenwriter Alvah Bessie, was coping less well than he with confinement, Biberman volunteered to serve extra time in Texarkana if his friend could be liberated early. This suggestion was rejected.

The activist and lecturer Jean Pfaelzer has likened the implicit philosophy of Salt of the Earth to the essentially optimistic musings on utopia by the German Jewish thinker Ernst Bloch. Whether by pinning hope on technology or other forces, things in general may improve, and the future can be “re-written, re-imagined.” Inspired by Kabbalah, Bloch believed that hope was a biological activity of the human mind. And Salt of the Earth centered on a domestic center of power and courage in the Jewish balabosta tradition, despite being located in New Mexico for the purposes of the story.

Filmdom has belatedly appreciated and echoed Salt of the Earth. A poorly received screen version of Biberman’s tsuris, One of the Hollywood Ten starred Jeff Goldblum as the director. And a more recent Audible podcast, The Big Lie, featuring Jon Hamm, Bradley Whitford and David Strathairn fictionalized the production process.

But none of these later recreations match the sheer verve of the 70-year-old original, created by a director who remained upbeat even in a Texarkana prison, and a producer with a similar glass-half-full attitude of Jewish hopefulness.

Indeed, Jarrico declared about the world travels necessitated by being shunned by Hollywood: “I would say that I personally found many positive aspects to being blacklisted. I don’t recommend being blacklisted to others. But it really allowed me to have experiences that I would not otherwise have had.”