Why a 100-year-old film about a ‘City Without Jews’ seems disturbingly prescient today

Hans Karl Breslauer’s 1924 film resonates in an environment of rising antisemitism and threatened mass deportations

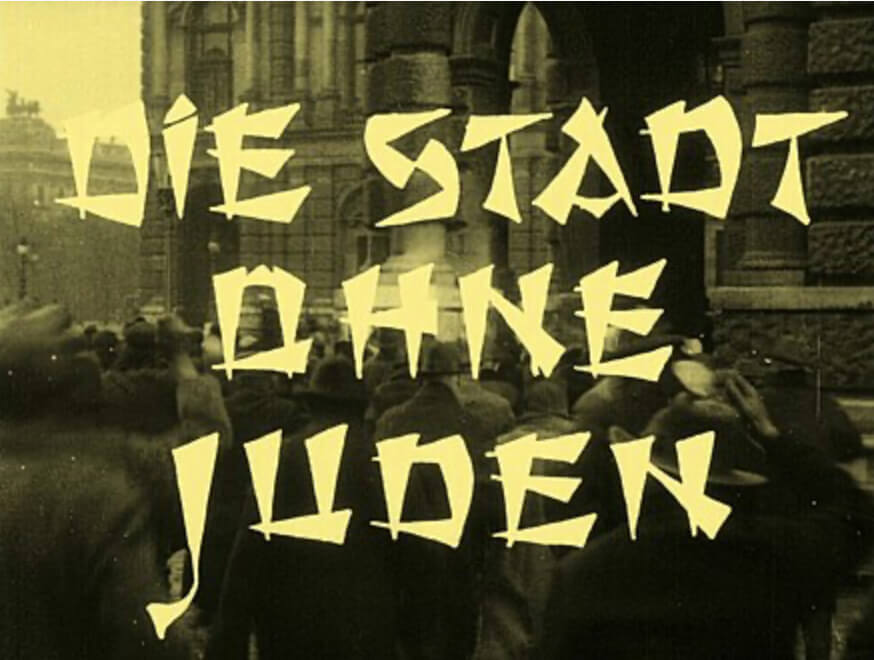

The 1924 film ‘The City Without Jews’ was directed by Hans Karl Breslauer. Courtesy of Center for Jewish History

Make Utopia great again — by deporting the Jews.

That is the premise of the 1924 German silent film, The City Without Jews, which was screened most recently at the Center for Jewish History by the Jewish Music Forum, with live accompanying music provided by Klezmer violinist Alicia Svigals and pianist Donald Sosin. The two composed the music during the COVID lockdown and have performed what they call “Cineconcerts” around the U.S., Canada and Austria, with more performances to come, including at New York City’s Anshe Chesed in May.

More than a century separates the film’s initial release from the audiences who view it today. But it remains contemporary in many ways. Incorporating Klezmer music “brings the score and the film squarely into the realm of Holocaust memory,” commented Frances Tanzer, Clark University professor and author of Vanishing Vienna: Modernism, Philosemitism, and Jews in a Postwar City. It is also, Svigals said, “an emotionally deep vision of what an expulsion is — how it’s one thing for a politician to placate their citizens….and then see people who are being expelled.”

The film opens with the announcement that “the legendary Republic of Utopia” (a stand-in for Vienna, the city in which the Jewish-born author Hugo Bettauer set his satiric, best-selling novel from 1922) is in turmoil. The stock market is flailing, and inflation has brought the price of eggs so high that disgruntled shoppers riotously hurl them at each other across the open-air markets. Meanwhile, mobs of protesters rowdily bear down on City Hall demanding change. There, the city’s cynical chancellor announces the solution: exile the Jews, including those who have been baptized.

Bettauer had intended his novel to be taken as a satire, written in response to the rise of antisemitism and growth of Hitler’s Nazi party. His narrative, Tanzer comments, emphasizes that Jews “were such an integral part of [Vienna’s] culture and everyday life….that removing them could only lead to absurdity.”

But overriding Bettauer’s objections, German director Hans Karl Breslauer (who eventually joined the Nazi party) reworked the script, incorporating both antisemitic stereotypes and violence against Jews. The film shows several men laughingly grabbing the long beard of a Jew while pedestrians quickly walk past without comment. At a crowded beer pub, drinkers shout, “Exile the Jews!”

Yet the film also documents solemn moments of the Simchat Torah synagogue service, depicting the rabbi, cantor and choir members lifting Torahs from the Holy Ark and carrying them through the sanctuary. Later, we see them lovingly remove and pack the Torahs as they exit the synagogue and march, this time — in a frightening foretaste of a future not yet known — towards the freight trains that will transport them beyond Utopia’s borders. I could not help but wonder if these poignant scenes were contributed by screenwriter Ida Jenbach who, as a Jew, was later exiled to the Minsk ghetto. Her date of death, whether there or in a concentration camp, is not recorded.

In composing the music for these scenes, Sosin and Svigals quoted sobering melodies from synagogue prayers such as the cantor’s hymn “Hineni” and “The Gates Are Closing” from the Yom Kippur service. Other scenes are filled with Klezmer melodies, reflecting, Sosin says, “the different layers of the Jewish population from all economic strata and all ways of worshiping within the Jewish community,” which we glimpse in scenes throughout the film.

Among the film’s assimilated Jews is Leo Strakosch, whose determination to marry his Christian fiancé despite his being forced to leave the country leads him to mastermind a zany plot that succeeds in welcoming back the Jews to Utopia. In the absence of Utopia’s Jews, the country is shown to have become impoverished culturally as well as economically — but many of the supposedly comic scenes are rooted in stereotypes of Jews as schemers or social climbers. But Leo, the charming conniver-in-chief, is played by one of the German heartthrobs of the era, Johannes Riemann. He also subsequently joined the Nazi party, and reportedly performed at an officers’ staff party at Auschwitz in 1944.

In yet another Nazi-era aftertaste, although the comedic Jewish actor Armin Berg, who garners laughs as a grocer who can’t stop noshing, was himself compelled to flee Vienna after the German take-over in 1938, cheering crowds and a sold-out theatrical appearance greeted him upon his return to the city in 1949. But he was refused access to his former residence, which had been “Aryanized” and which the government would not help him reclaim. For the next three years, he lived in a hotel.

The prolific journalist and novelist Bettauer himself did not have a happy ending. He was murdered in 1925 by a member of the Austrian Nazi party who, says Tanzer, contended that he was saving society from “Jewish degeneration.” Bettauer had become a target not only for criticizing antisemitism, but for supporting sexual liberation and feminism. “At this time the Nazi and other far right parties encouraged and did much to foment such violence,” and it was also typical for the left to receive “very heavy sentencing while the members of the right were frequently let off the hook.” This was true of Bettauer’s murderer who survived his light sentence — and World War II — maintaining throughout the rest of his life that the assassination was justified.

The film itself was long thought to have disappeared after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, until an incomplete copy was found in 1991, followed by the discovery of a complete print in a Paris flea market in 2015. The Austrian Film Archives subsequently sponsored a crowdfunding campaign that succeeding in raising money to restore it.

Viewing it today is a sobering experience, even when accompanied by Svigals and Sosin’s evocative Klezmer music. According to Evigals, People have been seeing the film in the context of resurgent antisemitism,” as well as viewing expulsion as relevant to the deportations threatened in the U.S.

After the YIVO screening, Chrystie Sherman, a professional photographer, commented on “the glaringly obvious comparisons between the German Weimar era and today; the story of 1924 is our story of today, demonstrating that life seems to only move in circles and not horizontally.”

The fate of Utopia remains an unresolved question.