Whoever said ‘you can’t take it with you’ never reckoned with this Jewish patriarch

The documentary ‘Death & Taxes’ explores estate law, entitlement, inheritance and the family legacy of former Sony president Harvey Schein

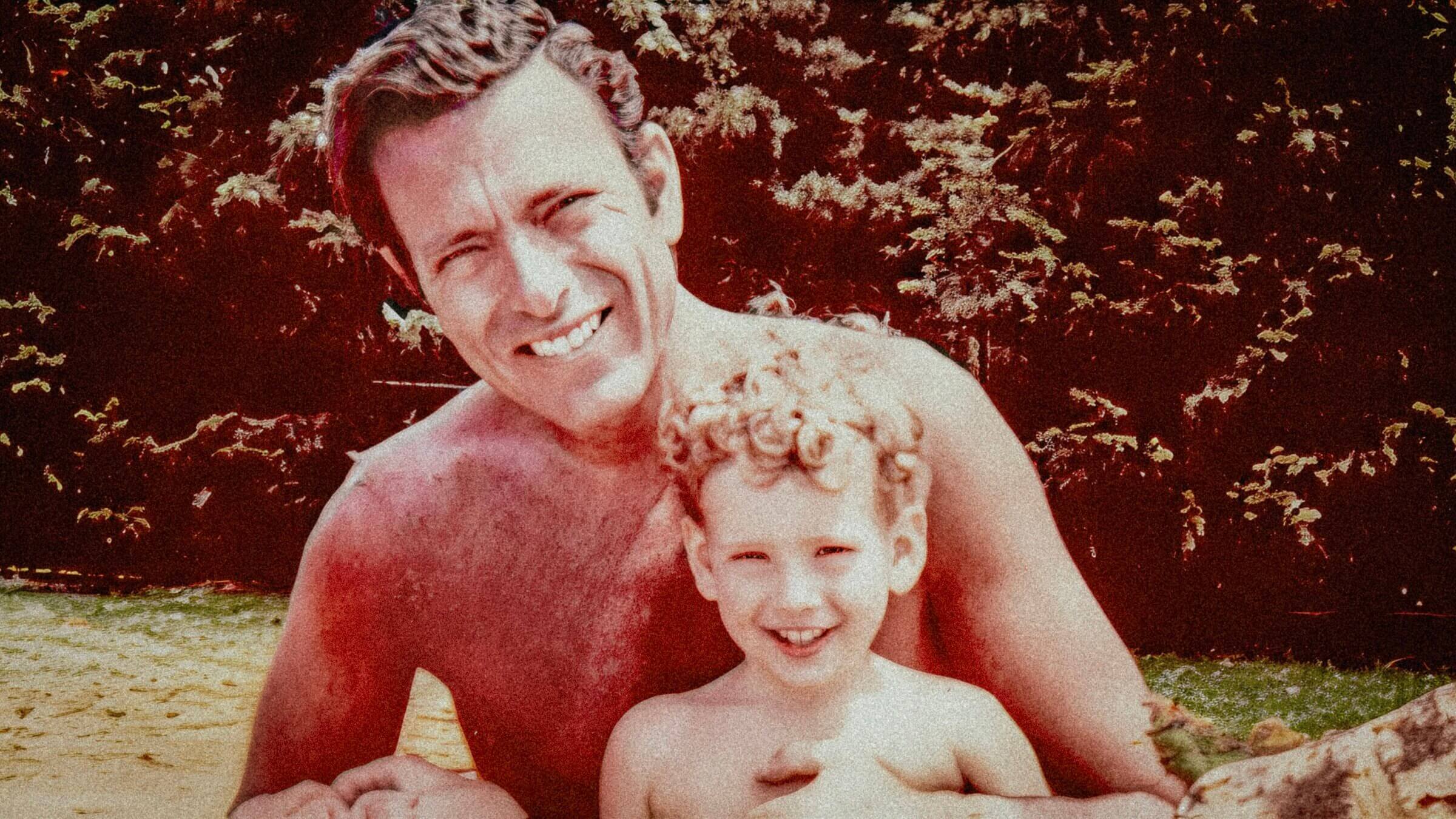

Harvey Schein and young Justin Schein, 1972. Courtesy of Schein Family Archves

A seamless, eye-opening documentary, Death & Taxes is at once a slice-of-life family memoir, a character study, a coming-of-age story, and a thoughtful probe into the whole murky topic of legacy and estate taxes.

Veteran filmmaker Justin Schein’s father, the late Harvey Schein, saw himself as the embodiment of the American Dream, whose go-getting attitude lifted him from poverty in Depression-era Brooklyn to great financial success as one of America’s top CEOs of the 1970s.

But the indisputably ambitious and driven Harvey Schein, who ran the American arm of Sony for many years, also spent the last two decades of his life fixated on trying to keep his hard-earned wealth from Uncle Sam — an obsession that arguably created a family crisis and brought to the surface a lifetime of festering wounds.

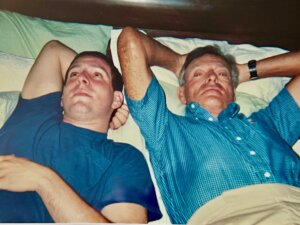

Filmed over a 20-year span and interweaving intimate family footage shot in the Scheins’ tasteful and well-appointed Connecticut home with prominent experts opining on all sides of the tax debate, Death & Taxes (co-directed by Robert Edwards) tells an unsettling story through the lens of one Jewish-American family.

Justin provides the backstory through voice-over narration. He also serves as an instructor to the audience, the majority of whom, in all likelihood, are unfamiliar with the byzantine world of estate (“death”) taxes, which affect less than 1% of the American population.

To be subject to an estate tax a single person’s assets (at the time of death) must be at least $13 million. For a married couple it’s close to $27 million. The federal tax, which does not include the state tax, may be as high as 40% or even 50%, though the very wealthy and their heirs find all kinds of loopholes and shelters to avoid paying anything.

The liberals interviewed in the film believe that the taxes should be far higher, arguing that these monies could be better employed to bankroll a host of programs that would benefit the public at large and especially underserved communities. For their part, conservatives like Harvey, who claim that the taxes penalize success, advocate “trickle down economics.” At one point, Harvey contends that the poor are poor because they refuse to work and that he and, by extension, his children and grandchildren are entitled to keep the money he earned.

Justin maintains that inherited monies and the entire tax system have perpetuated racial and economic inequity in the country, even though he acknowledges, and his dad frequently reminds him, that he wouldn’t have the career he has without his father’s backing.

Remarkably, without ever becoming heavy-handed or tedious, Schein incorporates such talking head experts as Paul Krugman, Matthew Desmond and Robert Reich. The latter observes, “If more and more wealth can be generated and provided to heirs without paying any taxes, then we are on the way to a permanent aristocracy in America.” At the same time, Justin gives his dad’s views a chance to be voiced by authorities as well, most notably by Republican strategist and pollster Frank Luntz, among others.

The son of garment workers, Harvey Schein was born in the Bronx and grew up in Brooklyn. After high school, he joined the Naval Reserve in 1945 and briefly served in the Pacific just after the end of World War II on the USS Octavia.

Thanks to the GI bill he was able to attend NYU before enrolling at Harvard Law School. He then joined a law firm where he worked on the CBS Records account. Later he became president of CBS and ultimately advanced to Sony where he became president in 1972.

A character right out of Mad Men, Harvey had a reputation for being aggressive, ruthless, manipulative and difficult to work with, but also charming and charismatic. His classic movie star looks did not hurt.

At home with his wife, Joy, and especially his two sons, Justin and Mark, he took frugality to a whole new level, frequently reiterating the need to turn off lights after leaving a room and to always use public transportation instead of taxis. His miserliness grew with time and, paradoxically, his mushrooming wealth. He frequently convened family meetings to discuss money matters. At least to this viewer, his penny-pinching obsession did not simply emerge from his experiences in the Depression, as many suggest, but rather bordered on some kind of psychopathology.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Harvey neither respected nor understood Justin’s ambitions to become a filmmaker — a career with no guarantee of financial stability which, in Harvey’s view, perversely violated a son’s primal instinct to outdo one’s father financially.

Despite their strained relationship, Justin had an abiding affection and later compassion for his father, especially as dad faced his own mortality. It’s illuminating that Justin started making the film as his father declined. The harsh criticism is mitigated by a pervasive sense of loss and nostalgia. The old black-and-white photos and home movies have their sepia glow. Justin says that as a child, he thought his father was like “a superhero.”

In stark contrast to his father, Justin emerges as a gentle soul, keenly aware from an early age of the wild discrepancy between his Upper East Side universe and the squalor and poverty that defined the lives of those who lived in nearby East Harlem. On his bus ride to the Horace Mann School in the Bronx, he’d stare out the windows at the pervasive despair and bleakness and feel deeply unnerved.

This film also explores the world of Harvey’s wife Joy who set aside her ambitions for a professional dance career to become a loyal and supportive spouse and mother — attentive, gracious and always on call.

The turning point issue for the Scheins occurred following Harvey’s retirement when he decided they would relocate to Florida for at least half a year every year because the southern state boasted a tax friendly environment. But Joy, who took dance classes in New York, did not want to leave. To placate her, Harvey built her a large studio in Florida where she could practice and invite other dance artists and companies to perform.

That did not satisfy her and in a surge of independence she moved back to New York and rented an apartment in the theater district. She had never been happier, she says, not least because she was away from Harvey and finally free from the “fear” he inspired.

It’s both easy and not so easy to empathize with her. Harvey was, indeed, unkind. “She practices and practices,” he says “but what has it gotten her?” On the flip side, both the studio in Florida and the New York apartment were made possible by Harvey. Far more poignantly, even if her whole marriage was a mistake and it wasn’t, she loved him, she was destined to be a permanent, aging dance student until she could not do that either.

In the end, Harvey developed lymphoma. As he rapidly deteriorated, his manic preoccupation with what he’d be able to leave his children and grandchildren and great grandchildren not yet born became an ongoing diatribe at a godless cosmos. At one point towards the close he quotes extensively from one of Macbeth’s soliloquies, which seems to comment on his own failures: “It is a tale told by an idiot — full of sound and fury signifying nothing.”

Harvey emerges as a complicated figure — not just pathologically tightfisted and obsessed with money but also committed to family, continuity and legacy. For him the latter can be purchased with an inheritance, the larger the better. He’s howling out to be remembered.

The narrative comes full circle when Justin and his wife give birth to a baby boy. As a dad himself, Justin develops a greater understanding of where his father is coming from and views him in a more forgiving light. It’s his rite of passage too even as he continues to view the meaning of heritage in a more philosophical context. He looks forward to the day when America can fulfill its promise to be a more equitable society. That, he says, would be the greatest bequest he could leave his children.