How the world transformed Elie Wiesel — and how he transformed the world

‘Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire’ traces its subject’s journey from Holocaust survivor to international hero and human rights leader

Elie Wiesel receives the Congressional Medal of Honor from US President Ronald Reagan, 1985. Photo by Getty Images

Perhaps the most torturous image in Oren Rudavsky’s searing documentary, Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire, is that of a child being hanged in Auschwitz.

Dangling from the gallows, his legs twisting this way and that, the child took half an hour to die because his body was so light. It’s a scene of relentless anguish witnessed by hundreds of concentration camp inmates who were brought together to collectively observe the punishment for crimes unknown.

“Behind me,” Wiesel recalls in voice-over, “I heard ‘Where is God now?’ And I heard a voice within me answer him, ‘He is hanging here on these gallows.’

Living in a godless universe where all morality has ceased to exist, Wiesel is nonetheless a profoundly religious man, a complex, contradictory figure. He is the iconic Holocaust survivor, witness, and storyteller, the latter his self-defined role.

The film, which depicts a philosophy, a sensibility, a life emerging from unfathomable Holocaust horror, is told through archival material and original interviews with historians, students and family members. The narrative is largely revealed through extraordinary expressionistic hand-painted animation by Joel Orloff. The black-and-white painted swirls start out as one picture, then merge and reappear as a second picture, and then morph into a third, and so on.

I’m generally not a fan of animation, especially in documentaries where its deployment can feel extraneous. But here, the animation is at once haunting and brutal and, most important, organic to the aesthetic, which subtly underscores the central themes. The evocative score by Osvaldo Golijov also works remarkably well.

Best known for the documentary A Life Apart: Hasidism in America, which he co-directed with Menachem Daum and was short-listed for the Academy Awards, Rudavsky has forged an intriguing and provocative fast paced flick that gives the viewer a glimpse into Wiesel’s private world.

As Wiesel recounts, his childhood in Sighet, Romania, was almost Utopian: Jewish children singing optimistic songs about a future in Palestine and lovely Shabbat dinners awash in candle light and ritual. Only later does he question his elegiac memories in a place he called home. Indeed, much of the film is about the power of memory and sometimes its distortions.

By the time Wiesel was 15 in 1944, his life had turned upside-down as the Nazis advanced, rounding up and deporting the Jews while the family’s gentile neighbors, who had previously seemed companionable and welcoming, sneered or looked away.

At Auschwitz, his family was torn apart. Ultimately, his mother, grandmother and sister were murdered, though two other sisters survived and were later reunited with him. Wiesel’s last image of his younger sister was the red coat she was wearing, a present for Passover.

His mother’s final words to him were to stay with his father no matter what, and he complied until his father succumbed from exhaustion and disease following their death march to Buchenwald. For the rest of his life, Wiesel was troubled by the voice of his dying father calling out to him, desperate to tell him something.

When the camp was liberated in 1945, a group photograph was taken. It features emaciated inmates including Wiesel, a gaunt, angular and spectral young man. Still, he was perhaps luckier than some of the others. He was sent to a French orphanage where he formed intense bonds with other youthful survivors. Luckier still, one of his survivor sisters, who was living in Paris, accidentally came across a photo of her kid brother playing chess at the orphanage which led to their emotional reunion. The element of randomness in life, though some might call it destiny, is a pervasive motif in the film.

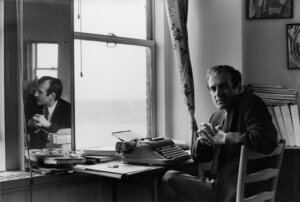

Throughout his journey, but especially in the early post-war years, survivor’s guilt gnawed away at Wiesel. Penance was a constant companion. In Paris, he lived in a dark, bleak room with one lit candle. He spoke to no one and his solitude was unremitting; that is, until he started writing.

The act of putting pen to blank page led to an outpouring of memory. In the end, immersing himself in every grotesque Holocaust moment paradoxically distanced him from the memory, and at the same time gave him a small degree of control over an incomprehensible narrative.

But far more important in his view was the role he played as witness, to share with as many as possible what he had experienced and seen. In so doing he believed he honored those who had perished and hopefully helped prevent future Holocausts.

“Your enemy’s greatest fear is your memory,” he said.

He first wrote Night, his major autobiographical opus, in Yiddish, his native language, but was unable to find a publisher. According to some accounts, his first draft was far too long and expressed overly embittered criticism towards the non-Jewish world. The French version (and later English translation) was trimmer and far more existential in tone. God was at fault. Regrettably, without elaborating, Wiesel explained that writing in French, which became his language of choice, changed what and how he wrote.

During the course of his lifetime, he authored more than 50 books, mostly nonfiction, but also novels, none of which used the Holocaust as a backdrop. His two novels, Dawn and Day that form a trilogy with his memoir, Night, raised ontological questions in a post-Holocaust world.

He was adamantly opposed to Holocaust novels or dramatizations, arguing that the Holocaust was so beyond the imagination of any writer, that in writing a Holocaust novel or play the writer trivialized it and, worse, abused both the survivors and especially the dead.

In one of the film’s most disquieting moments, one of Wiesel’s students asks him to reveal the numbers tattooed onto his arm. The class is silent and immobile as Wiesel removes his jacket, rolls up his sleeve and matter-of-factly holds up his arm.

Wiesel taught at Boston University for four decades and he was a professor who transformed lives. For many pupils, he represented a turning point encounter in their understanding of a remarkable survivor in a world gone mad.

When he was 40, Wiesel also had a turning point encounter. Until then, he had few, if any, strong personal or romantic relationships and he was determined not to bring children into this world. But that all changed when he met Marion, an attractive, brainy Jewish woman who characterized herself as a pagan. Shortly after they met, they were married and had a son.

Wiesel grew into an international figure, speaking across a global stage about the atrocities of the Holocaust and the long shadow it cast, lest anyone forget or diminish its significance.

Most memorably, and beautifully handled in the film, was a scene that took place just after Wiesel accepted the Congressional Gold Medal in April 1985. The event served as a springboard for an iconic, yet stunningly diplomatic, face-off between Wiesel and President Reagan in connection with Reagan’s plans to participate in a ceremony at Bitburg military cemetery that housed the graves of SS troops.

Though Reagan insisted that there was no parity between Nazi soldiers and concentration camp victims, he said that his trip to Germany, which also included a commemorative trip to Bergen-Belsen, was a necessary gesture at reconciliation.

“That place, Mr. President, is not your place,” Wiesel said. “Your place is with the victims of the SS. The issue here is not politics, but good and evil. And we must never confuse them.” For me, Wiesel’s imploring tone and words bordered on groveling.

Still, Wiesel was a human rights activist and he never shied away from voicing his advocacy on behalf of those he viewed to be victims, whether they were inhabitants of the former Yugoslavia in the early 90s or the Palestinians.

In 1986 he received the Nobel Peace Prize.

Towards the end of the film, we see Wiesel back in Sighet walking among the broken down and decaying tombstones in an ancient Jewish cemetery. This, he says, is where he feels most at home.

Like so much else in this strong work, these comments are cryptic and open to interpretation. Though Soul on Fire exposes the viewer to a very private Wiesel, he still remains unknowable. He died in 2016 at the age of 87.