Bob Dylan, my mother, and the unknown painter behind ‘Blood on the Tracks’

Dylan once said that Norman Raeben was the man who ‘taught me how to see’

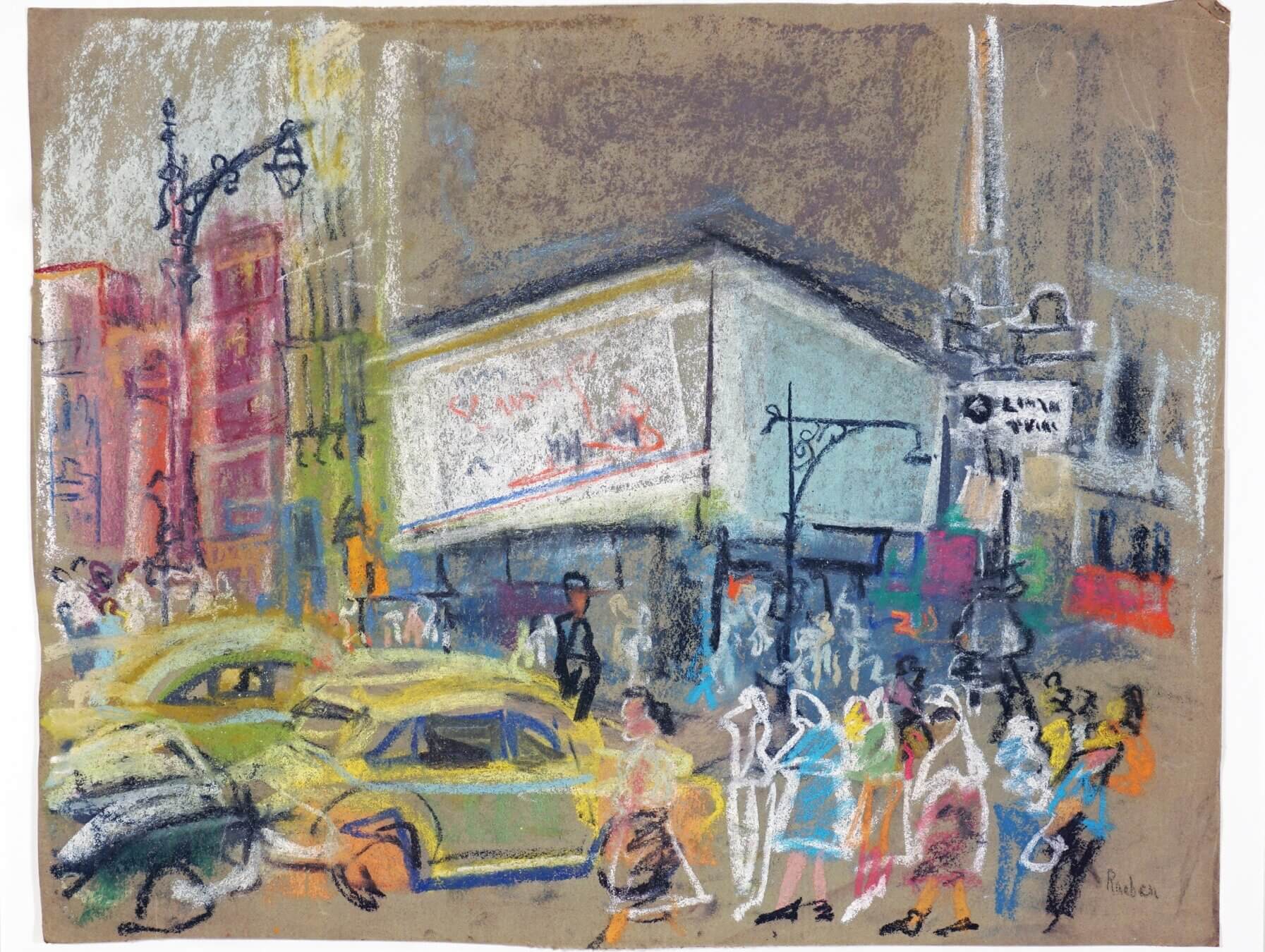

‘Untitled,’ by Norman Raeben, dated between 1932-1950s. Courtesy of Josh Raeben

The period in which Bob Dylan struggled through personal and artistic crises to write Blood on the Tracks is veiled with mystery. Dylan has rarely discussed the origins of his most revered album. He hardly wrote about it in his memoir, Chronicles: Volume One, except to claim that Blood was inspired by Chekhov stories rather than his divorce. “A lot of people tell me they enjoy that album,” Dylan infamously told Mary Travers in 1975. “It’s hard for me to relate to that. I mean, people enjoying that type of pain.”

I know a few things about this period in Dylan’s life, because my mother had a romantic relationship with him at the time. He wrote portions of Blood on the Tracks in the New York apartment in which I live today.

One of the few public comments Dylan has made about Blood is to credit its genesis to Norman Raeben, his enigmatic Ukranian-Jewish painting teacher. When Dylan walked into Raeben’s studio, my mother was a student in the class, twenty years old and recently arrived in New York to pursue her ambitions as an artist. As I wrote in a memoir essay in Harper’s Magazine,” The Silent Type: On (Possibly) Being Bob Dylan’s Son,” my mother and Dylan soon began a romantic relationship. She later recounted to me that he often played her the songs that became Blood on the Tracks, and spoke to her about how their painting teacher was influencing what came to be regarded as Dylan’s greatest album.

“He taught me how to see,” Dylan later told Rolling Stone. “He put my mind and my hand and my eye together in a way that allowed me to do consciously what I unconsciously felt…I had met magicians, but this guy is more powerful than any magician I’ve ever met. He looked into you and told you what you were.”

The story of Raeben’s transformative influence on Dylan in this pivotal moment of his life has never been fully told. Two recent painting exhibitions offer glimpses into the story.

In London, the Halcyon Gallery exhibited “Bob Dylan: Point Blank,” a show of ninety-seven new paintings, this past May 9 to July 6. A thousand miles southeast and a few months before (November 24, 2024 to March 9, 2025), the Venice Jewish Museum exhibited, “Norman Raeben (1901-1978): The Wandering Painter,” the first retrospective of Raeben’s life work.

Dylan met Raeben at a low point in his creative life. It was 1974 and for years Dylan had sequestered himself away in upstate New York, certain that he had to escape celebrity to write meaningfully. He’d released seven albums in eight years but wasn’t satisfied with the work. He was 33 and felt his best music had been written before he was 25. He sensed that if he didn’t find his way back soon, he never would. One day, he overheard friends of his wife, Sara, “talking about truth and love and beauty and all these words I had heard for years, and they had ‘em all defined. I couldn’t believe it…I asked them, ‘Where do you come up with all those definitions?’ and they told me about this teacher.”

Nochum Rabinovich was born in the Russian Empire in 1901, the youngest child of the great Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem. When the family immigrated to New York, in 1914, he took the name Norman Raeben. As a young painter, he came under the influence of Robert Henri and the Ashcan School, and won critical acclaim for synthesizing figurative realism with the high modernism of the School of Paris. Raeben’s aesthetic commitment was to the mundane beauty of ordinary life. He believed that painting was a way of life, a method of seeing, that the artist must learn to react to every moment and thus heighten the experience of life itself. Raeben studied and exhibited beside contemporaries ––Rothko, Chagall, Soutine–– whose work, like his, sought to bridge old world Yiddish culture with the vitality of Paris and New York. Then, in the 1940s, Raeben suffered a debilitating mental breakdown and ceased to exhibit his work. He retreated to an 11th-floor studio in Carnegie Hall, where he taught grueling painting classes and was largely forgotten.

Raeben’s work is almost exclusively held in private hands, with the notable exception of several works at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Norman Raeben (1901-1978): The Wandering Painter” comes with a 126-page catalogue, compiled by art historian Fabio Fantuzzi, that is the most complete compilation of Raeben’s work. From the 1930s onward, Raeben did not title, date, or sign his paintings. Looking through his oeuvre feels like a journey through memory, with no official beginning or ending. Raeben’s paintings often appear as photographic flashes: Cars, streets, sky, and light merge together for one kinetic moment. In an untitled work dated in the catalogue as “1932–1950s,” two yellow cabs maneuver through what appears to be a Manhattan street. Crowds hover on either side of the cabs; the street is not marked by any sidewalk or dividing line. The whitewashed building at the center of the canvas seems pressed inward by the sheer force of the city. Look once and see urban chaos; look twice and all is held together by the calm logic of Manhattan in motion — and Raeben’s steady eye. This is painting as Raeben understood its purpose: a reaction to an ordinary moment, a way of seeing the every day.

Raeben understood himself as part of a vanishing tradition, the sliver of breathing room between figurative painting and high modernism that he forged under Henri’s inspiration. He castigated the dominant styles of the century — Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, Pop Art — and referred to the tastes of the postwar New York art world as “idiot wind,” a phrase Dylan borrowed. In his Carnegie Hall studio, Raeben sought to pass on what he knew to anyone determined enough to learn. Raeben spoke in Yiddish, English, French, Ukrainian, and Russian as he painted, often explaining his aesthetic theories by way of Proust. Raeben valued artistic diligence above all else: The studio floor was cluttered with rags and stained with thick impasto paint. He could be brutal. My mother told me that he once flicked paint off a brush into the eyes of a younger student, shouting, “You like being blind? Everything you’ve done is worthless!”

Dylan arrived at Raeben’s studio in spring 1974. Soon, my mother later told me, he was playing guitar in her third-floor walk-up in Yorkville and explaining why Raeben seemed to him like a prophet. Raeben, Dylan said, was teaching him that his problems were rooted in the wrong perspective of time. Raeben understood that, “You’ve got yesterday, today and tomorrow all in the same room,” as Dylan later told Rolling Stone. Raeben, Dylan told my mother, painted in one stroke from the perspective of his Russian childhood and Parisian twenties and New York middle age. He slipped between languages, colors, thinking, feeling, time. Dylan often told my mother that he felt blind and Raeben was teaching him how to see. He wanted to write music with the multiplicitous perspective with which Raeben painted. He wanted to transform the rawness of his inner life into music, the way that Raeben believed that the most worthwhile painting came from reacting to the depth and impulse of feeling.

One night that summer my mother’s phone rang in the early morning hours. Dylan was on the other line, singing before he said hello. It was a new song about a man in search of lost love. In each stanza the man and the woman were always the same people and always different people. Dylan shifted between first person and third person. Every stanza described the present while imagining the future and recalling the past. Dylan told my mother he was calling the song “Tangled Up in Blue.”

Later, Dylan would write of “Tangled,” on the jacket of Biograph, his 1985 compilation album, “I was just trying to make it like a painting where you can see the different parts but then you also see the whole…with the concept of time, and the way the characters change from the first person to the third person, and you’re never quite sure if the third person is talking or the first person is talking. But as you look at the whole thing, it really doesn’t matter.”

Last month, I went to see “Bob Dylan: Point Blank” at the Halcyon Gallery in London. Dylan paints melancholic landscapes and portraits at once ordinary and mythic. It’s not work that sits easily within any major postwar tradition––except the one stubbornly taught by Norman Raeben. Dylan’s eye drifts to the banal beauty of everyday life to which Raeben devoted his work. He paints the interior of American homes, creaky floorboards, open doors that lead nowhere. Gray garages on autumnal brick roads. Men in tuxedos, kings of their small town. Egg cartons, grandfather clocks, pocket mirrors, binoculars, old pick-up trucks; no object is too plain for the painter’s gaze. There’s a hint of self-portraiture in the young man with a pen and a spiral notebook. There’s a quick-draw artist, too; maybe the man in “Idiot Wind” who “shot a man named Gray / and took his wife to Italy.”

In a series called “Train Crossing (red),” Dylan situates us behind the wheel of a train, rendered in varying color schemes in four otherwise identical paintings. The train track below hurtles us inexorably toward the horizon at the high end of the frame. “The only thing I knew how to do,” Dylan sings in “Tangled,” “was to keep on keepin’ on,” and these tracks give us no other choice. Staring at those tracks, I wasn’t sure for a moment where I was. The London gallery and Raeben’s studio and the Yorkville apartment in which Dylan wrote and my mother and I lived fifty years apart were all happening at once, that train taking me into the past and future on the same line. If you’d asked me where I was standing, I don’t think I could have said.